-

Union Bank garnered high marks from customers in almost every key area of our most recent survey on bank reputations. CEO Masashi Oka explains the approach that produced these results.

June 25 -

No bank in our annual survey of reputations has done a better job of positioning itself on long-term trust issues than BMO Harris Bank, which outscored the field when we asked consumers whether they'd give their bank the benefit of the doubt when the next crisis hit.

June 25 -

The changing nature of the news business doesn't change Editor in Chief Heather Landy's basic advice about dealing with press.

June 25

It's probably not much of a consolation to bankers to know that the financial services industry, which has a poorer reputation than any other major sector of the U.S. economy, still seems to be held in higher esteem than Congress.

But the reprobates on Capitol Hill at least provide an instructive example of how, at the individual level, it is possible to rise above the very negative perceptions people may have about the institution to which you belong.

You know that old saying about how Americans hate Congress but love their congressman? There is a similar dynamic at work in the U.S. banking system. Five years after the financial crisis began, the industry remains deeply unpopular. The foreclosure debacle involving the largest mortgage servicers, the London Whale incident at JPMorgan Chase, the money-laundering probe into HSBC-all of this has only accentuated the public's mistrust of the banking sector. But ask consumers what they make of their own banks, and the results may pleasantly surprise you.

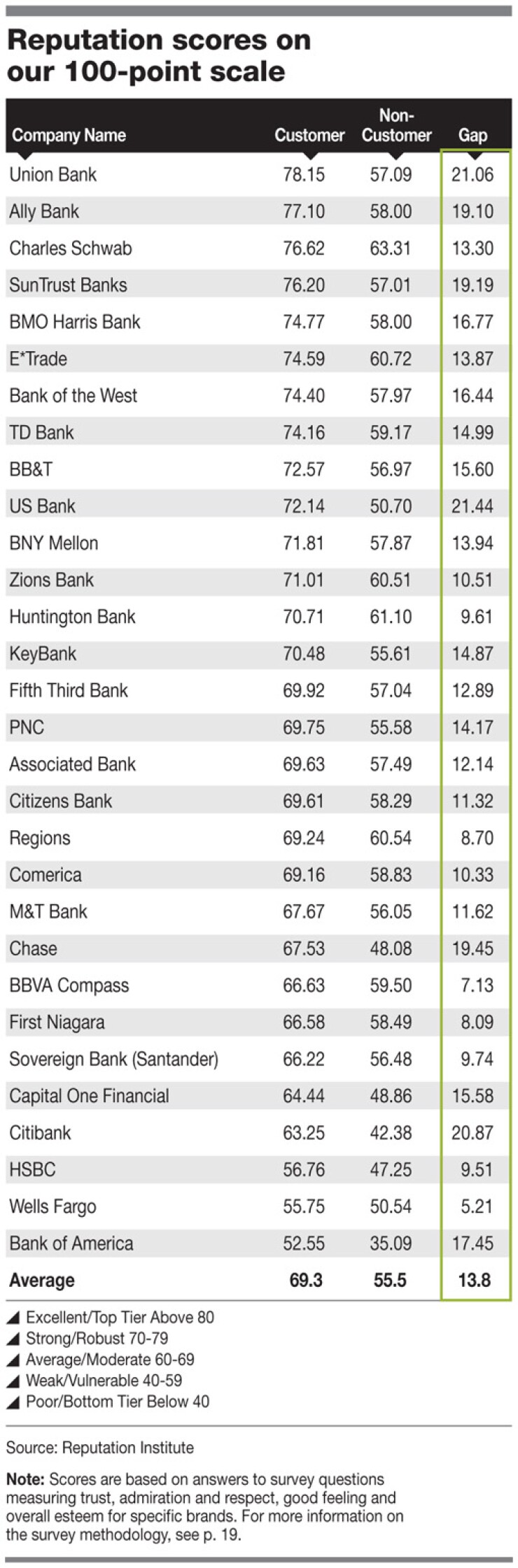

Nearly half of the 30 major brands studied in this year's American Banker/Reputation Institute Survey of Bank Reputations enjoy a strong reputation with customers. Led by San Francisco-based Union Bank, these institutions scored above 70 on our 100-point scale. (According to Reputation Institute, a reputation management consultancy, a score of 70 or better indicates reputational strength.) Another large slice of the banks in the survey performed moderately well with customers, leaving only three brands (HSBC, Wells Fargo and Bank of America) with scores below 60, which indicate a weak or vulnerable position.

Scores from noncustomers paint a far more unsettling picture, however.

Here, not one bank managed a score above 70. Only five mustered moderate scores, Charles Schwab and Huntington Bank among them, while 22 of the 30 were in the weak-to-vulnerable category. One bank, BofA, did even worse than that. Its score of 35.1 put it in the "poor" category, the lowest tier on Reputation Institute's reputational hierarchy.

Overall, brands in the survey averaged a score of 69.3 among customers and 55.5 among noncustomers. This nearly 14-point gap is far more significant than is typical of other industriesand wider than the gap of 7.3 points in last year's surveyand indicates that banks will be in reputation rebuilding mode for quite a while longer, according to Anthony Johndrow, a managing partner at Reputation Institute.

"These scores with noncustomers don't present much opportunity in the near term," Johndrow says.

Even among their own clients, banks "have a long way to go to shore up customer relationships before they can expect any favors from them." Those favors would include things like recommending a specific bank to friends and family members (or, these days, to anyone following them on social media), purchasing additional products and services that expand the customer relationship or simply giving a brand the benefit of the doubt in times of trouble.

The difference in scores from customers and noncustomersseparated for the first time since the inception of our surveytells an interesting story about the state of individual bank reputations.

Citibank, for example, still tends to get lumped together with BofA when consumers think about the poster children for the crisis bailouts and the ongoing too-big-to-fail debate. Citi had a reputation score of 42.4 from noncustomers, barely putting it over the edge that separates weak or vulnerable brands from the brands with the poorest public images. But among customers, Citi had a score of 63.3, which is in the moderate category. The wide gap may indicate that direct interactions with the bankwhich has been ramping up investments recently in its long-neglected U.S. branch operationshave neutralized some of the bad publicity Citi got in 2008 and 2009.

Meanwhile, Huntington Bank, which had one of the smallest gaps between scores from customers and noncustomers, appears to have made an impression on the public at large. The bank's highly publicized 24-hour grace period on overdrafts and its renewed commitment to free checking, announced just when rivals had started pulling back on such accounts, perhaps helped here.

As in past years, institutions with a heavy online componentfrom a direct bank like Ally Bank to more investment-oriented brands such as Charles Schwab and E*Tradeperformed well among consumers.

These nontraditional banks averaged higher scores among customers and noncustomers versus the biggest banks and the regional players. And Schwab swept virtually every key category that figures into the overall impression that consumers form about the banks with which they do business, outscoring the 29 other banks on products, performance, innovation, citizenship and leadership. On two other key components of bank reputation, perceptions about governance and the workplace environment for employees, Schwab ranked second, trailing only Union Bank in these categories. Schwab was nearly as dominant in the rankings based on the survey responses of noncustomers, garnering the highest or second-highest score in each category except workplace and citizenship, where it failed to place in the top five.

Among the big reputation drivers, products and services together make up the largest factor in the development of brand perceptions by a bank's customers, according to Reputation Institute's analysis. (For noncustomers, governance is most important, followed closely by products and services.)

Miles Everson, head of the financial services advisory practice at PwC, says banks have made recent progress on both of these fronts. "Their attention to reputation is as high as I've ever seen it," Everson says. "And they're going beyond just the message on reputation; they're looking at whether they're substantively doing things" that will repair public trust.

In some cases, it is regulation that is driving the improvements, such as the "single point of contact" that servicers were forced to create for troubled homeowners, under the mortgage settlement reached in 2012 with the Justice Department and 49 state attorneys general. But in other cases, Everson says, banks are making smart, voluntary decisions that can help improve perceptions, be it the offering of convenient new services such as remote-deposit capture or a whole shift in mindset as to how to treat customers.

Says Everson, "That's actually the salient question: Are you treating people fairly, first, so you can drive reputation?"

As the public continues to sort out the collateral damage from the most recent financial crisis, it's tough to envision banks approaching the reputational solidness of brands such as Amazon.com, Kraft Foods, UPS and Johnson & Johnson, all perennially strong performers in Reputation Institute's omnibus survey of 150 corporate brands across sectors. (Those companies all had 2013 scores between 79 and 80 in that survey, which covers 150 of the largest U.S. brands. The top two brands, Walt Disney and Intel, crossed the 80-point threshold, putting them in the highest tier on Reputation Institute's 100-point scale.)

But Johndrow says that as recently as 2008, banks had cracked the top 30 in the omnibus study, where the results are based on a mix of scores from customers and noncustomers.

"There is no inherent reason why a bank couldn't top the [broader] list" eventually, Johndrow says. But "being a bank is an automatic penalty now."

So the trick, he says, "would be to either reposition yourself as something other than a bank-credit unions and local banks are already reaping the benefits of not being seen as big banksor dig down deep and give the public a specific, believable reason to believe that your bank is structured to do the right thing for your customers and society."

The latter was the path that Union Bank chose this year when it began its "Doing Right" campaign, with advertisements featuring the actor and activist (and longtime Union Bank customer) Edward James Olmos and the author Maya Angelou, separately reflecting on concepts such as honesty and fairness, trust and integrity. "What we want to do is do right. But you have to say it, you have to show it, and not stop," Angelou says in one of the minimalist-style spots. The campaign, by the advertising agency Eleven, launched in January and ran on the West Coast during high-profile television programs including the Super Bowl, the Grammy Awards and the NCAA Final Four.

"Early research indicates significant gains in awareness of Union Bank," says Pierre Habis, senior executive vice president for retail banking at Union Bank. (Related:

"We have received numerous emails and letters from current customers that appreciate our advertising what we stand for and believe in as a financial institution," Habis says. "We also have received very strong feedback about this message from community groups, business leaders, regulators and local politicians."

Union Bank perhaps has the credibility to market itself with a slogan about doing rightit stayed out of subprime lending, for instance. But Johndrow says most large banks don't have permission yet from the public to talk about themselves in this way.

This doesn't mean banks need only play defense on matters of reputation management, but they might want to consider alternative forms of offense that will prevent them from offending the sensibilities of both customers and noncustomers.

For this, Johndrow says he recommends "activities that engage influencers and communities in a way that adds value and demonstrates the value banks can bring to communities." Banks that can accomplish this, he says, will "build up the ability and permission over time" to tell their story more broadly.

SURVEY METHODOLOGY

Company Selection:

- Companies were drawn from the Federal Reserve's list of large commercial banks as of Dec. 31, with final selections determined by American Banker based on the size of each firm's assets and deposits. Only companies with significant retail businesses and/or significant retail brands were considered

Ratings:

- Ratings were collected via online questionnaire in February and March 2013

- Each respondent was familiar or somewhat familiar with the company they rated

- All companies were rated by at least 100 customers and 200 noncustomers