WASHINGTON — Zcash, the cryptocurrency that debuted last week, promises transactional privacy on an open blockchain. That could make distributed-ledger technology more appealing to financial institutions, but perhaps less so for regulators.

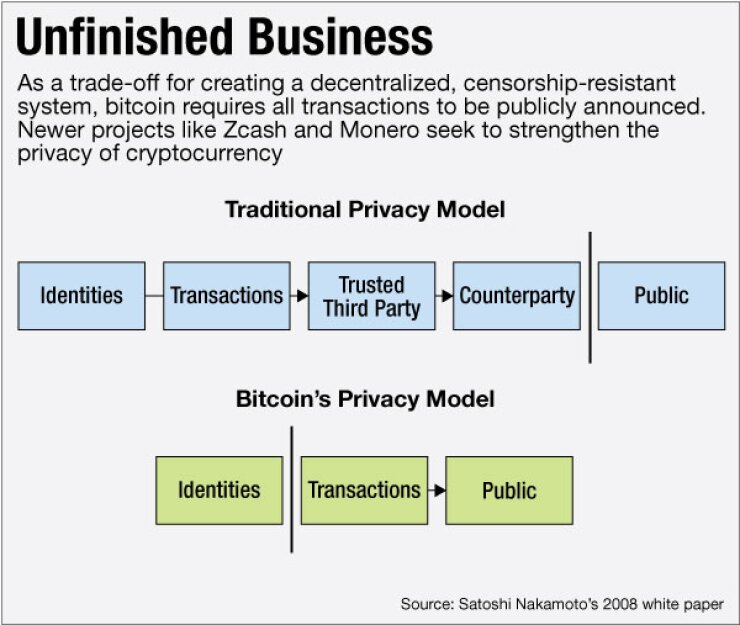

The blockchain — the shared-ledger system pioneered in bitcoin — is often touted as a more efficient, transparent and resilient way to record transactions. A

"If you're JPMorgan, you can see all of Credit Suisse's books, and neither JPMorgan nor Credit Suisse is comfortable with that degree of transparency," said Peter Van Valkenburgh, the research director at Coin Center, a cryptocurrency advocacy group in Washington.

With Zcash, the software developer Zooko Wilcox offers a solution to this problem. If the technology works as envisioned, it could not only make blockchains more palatable for banks but help resolve long-simmering tensions between anti-money-laundering regulations, which demand transparency, and financial privacy. What remains to be seen is how governments will view a system where transactions are auditable but disclosure is under the participants' control.

Starting with the same basic framework as bitcoin, Wilcox added a recent cryptographic innovation, called the

This system allows users to conduct private transactions while maintaining the integrity of the blockchain that supports them. As in bitcoin, users are identified by pseudonymous addresses. Those alphanumeric strings alone do not guarantee privacy, since the flow of funds can be traced through the blockchain and addresses controlled by the same user can be linked.

In Zcash, there are two types of addresses, "transparent" and "shielded." The transparent addresses and the amounts sent to and from them show up on the blockchain as they would in bitcoin. But if a user opts to use a shielded address, it will be obscured on the public ledger. And if both the sender and receiver of funds have opted to use shielded addresses, the amount sent will be encrypted as well.

Eventually, the Zcash development team will add "view keys" that users will be able to share with third parties to reveal information about their own transactions — though not anybody else's.

"We call this 'selective disclosure,' " Wilcox said in a statement to American Banker. "It also comes with an encrypted memo field, which allows institutions to safely attach sensitive data to transactions, and make that information visible to authorized parties."

Otherwise, the blockchain operates normally; the ledger knows that the amount of funds in the system before and after each transaction remains the same.

What a zero-knowledge proof "potentially gives you is the ability for you to prove something about a data structure without revealing the data inside the data structure," Van Valkenburgh said.

For banks intrigued by blockchains but leery of

"With encryption, you can actually get many or most of the properties of transparency and privacy and data security at the same time,"

After pausing work on ZSL to make sure the cryptocurrency was released on time and securely, the firm is now tending to both projects simultaneously.

"Our code is getting a trial by fire on

An obvious question is whether the Zcash currency's privacy features will make it more difficult for the financial institutions involved — such as digital currency exchanges and wallet services, or their banking providers — to comply with anti-money-laundering regulations.

On the one hand, Zcash's "selective disclosure" capabilities, combined with the pressure on intermediaries to comply with AML rules, would ensure that most transactions are traceable.

The work of collecting basic transactional data for AML purposes would likely be performed by third parties like wallets and exchanges.

To comply with rules for money-services businesses, or simply by virtue of needing to satisfy their bank partners, these companies would have to obtain data on the parties in each transaction and other information to ensure that they can flag suspicious transactions.

"All of that same compliance infrastructure still needs to be in place," said Pratin Vallabhaneni, an associate at the law firm of Arnold & Porter. "If you're a user of Zcash thinking, 'Oh, I'm going to have a more anonymous transaction,'" he added, "that's not correct because you won't be able to enter into the [rest of the financial] ecosystem" without disclosing basic identifying information.

In addition, financial institutions could use the selective disclosure system to cooperate with law enforcement in investigations. In fact, this would be a relatively smooth process thanks to the blockchain.

Similarly, the memo feature would simplify compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act's travel rule, which calls for a sending financial institution to pass along information on each transaction to the recipient financial institution. Under Zcash, all banks would need to do is share the view key with their counterpart.

"This makes compliance a little bit easier," Van Valkenburgh said.

On the other hand, Zcash could take away law enforcement's ability to conduct blockchain analytics, which can help narrow the field of real-world suspects. Instead of being all in one place, the identifying data would instead be likely dispersed among the intermediaries — the wallets and exchanges.

"A lot of that [analytics capacity] is removed with the shield-based transaction protocol," Vallabhaneni said. "It would increase the amount of work that law enforcement agencies might probably do with the intermediaries."

Meanwhile, Zcash admirers say, the privacy afforded by zero-knowledge proofs could allow financial institutions to enjoy the benefits of an open blockchain while complying with privacy rules, like those under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.

"This is a technology that's being designed very deliberately to both protect people's privacy and permit authentication of that information," Van Valkenburgh said.