Though established over 70 years ago, Salal Credit Union in Seattle only began exploring business banking in 2012. And at first, it took clients at their word.

“We were still in the infancy of our business banking growth,” said Russell Rosendal, chief executive and president of the $594 million-asset credit union. “They might say that they were a flower business or something like that.”

Due diligence afterward caught customers that didn’t disclose they were in fact selling medicinal marijuana (legalized in Washington state for medical purposes in 1998 and for recreational use in 2012), but the issuance of the Cole Memo persuaded the credit union to openly bank these marijuana-related businesses. Still, in states where marijuana remains illegal, many banks and credit unions are likely banking MRBs without knowing it.

“Most bankers assume that whatever [business clients] put down to be honest, which is a fundamental flaw,” said Steven Kemmerling, founder and CEO of MRB Monitor, which specializes in identifying and managing marijuana-related risk. “Almost no owners volunteer that they are owners of a marijuana business.”

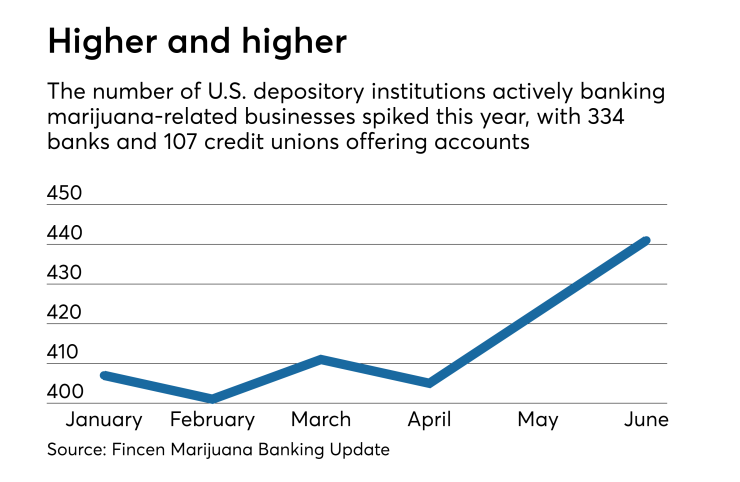

The number of depository institutions banking MRBs is at a high point, according to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or Fincen. Based on suspicious activity reports, the government counts 334 banks and 107 credit unions that are offering accounts to such businesses.

After its experience, Salal strengthened its vetting. Previously it would do on-site visits to business clients six months after they opened accounts. But now it visits businesses on-site before an account is opened. The credit union also installed Verafin, an anti-money-laundering and fraud detection software.

Kemmerling says banks and credit unions should include MRB questions in the due diligence process, a practice that Sundie Seefried, CEO of Partner Colorado Credit Union in Arvada, instituted at the $387 million-asset institution.

“Before you start looking at transactional data, the first step is always due diligence,” Kemmerling said. “What’s the true nature of the account? Why rely on behavioral analysis when you can have a better understanding of what they are from the beginning?”

While most financial institutions have "no marijuana" policies, they lack effective controls to enforce that, Kemmerling said.

MRBs that aren’t being honest about their business have some observable characteristics, said James Collins, CEO of the $293 million-asset O Bee Credit Union in Tumwater, Wash.

Suspected customers can be checked to see that transactional data lines up with what the business said in due diligence, Collins said. “They have friends who do deposits for them rather than themselves. They’ll go to different branches to make deposits. With a good [Bank Secrecy Act] system, you should be able to catch that.”

MRBs that aren’t being honest about their business also don’t like cash transaction reports, Collins added. When a business deposits more than $10,000 it triggers a currency transaction report, which the financial institution forwards to Fincen. “It’s a good way to find people who are structuring or laundering money,” Collins said. “So they’ll deposit $9,500 every day.”

Collins has also run into accounts that were undisclosed MRBs operating a bank account for the purpose of paying taxes. These businesses would keep most of the cash to themselves and deposit only enough to pay federal income taxes. Savvier businesses will also keep multiple accounts open at multiple institutions.

“Yet even if they have a very low transaction amount and usual cash amounts, what they told you in due diligence and what they do will almost always be different,” Collins said. “It’s just the larger institutions like regional banks only have a few people monitoring a lot of accounts.”

However, O Bee has it easier than the average bank or credit union. Members who are owners of MRBs will turn in other MRBs if they know they’re not being honest with the institution, Collins said.

O Bee also primarily has a retail membership. “It would be a lot harder if we banked more businesses,” Collins said. “Mini Mart would be looking like a marijuana-related business with its heavy cash deposits.”

Yet, even financial institutions that support banking MRBs still are concerned about businesses hiding their true sources of income. In the next few months, Seefried plans to have MRB Monitor run its software against Partner Colorado Cred Union’s portfolio to ensure that each of the credit union’s clients are who they say they are.

“They don’t need to ride under the radar here,” Seefried said. “But the fines are severe if you don’t catch something. I think we’ve been public enough that they realize they’ll be welcome here, but you never know unless you run the program.”

Seefried says every financial institution — not just banks and credit unions open to pot banking — should be looking for MRBs in their risk analysis. However, finding talent to scan for under-the-radar MRBs requires expertise, said Adam Crabtree, founder and chief executive of NCS Analytics, a platform that tracks high-risk industries for government customers.

“When you talk about the bankers that are able to accurately and wholly do this, you're not talking about your run-of-the-mill, first-job-out-of-college banker,” Crabtree said. “You're talking a more sophisticated individual. The banks that choose to do this have to invest in bankers that are more expensive.”