For Bill, now in his 50s, uncontrollable spending was one of the earliest signs of bipolar disorder.

He was in his early 30s and gainfully employed when he first began to experience symptoms of mania. Bill eventually lost his job and began collecting Social Security disability income. When it was determined that Bill could not manage his own finances, his sister was appointed as his representative payee.

Then things quickly went awry.

His sister would skim money from his account whenever she bought his groceries, Bill recalled. He never knew quite how much he had, and over a two-year period, she stole about $18,000 from him. Once he figured out what was happening, Bill was able to get a different representative payee, but his relationship with his sister had been shattered.

By the time Bill recounted this story to researchers with Yale University, he had not spoken with her in three years.

Bill is not his real name, but his story illustrates how the traditional financial system falls short when it comes to helping people with mental health issues manage their money. A recent collaboration between Yale University’s psychiatry department and law school aims to raise awareness of the issue and encourage financial institutions to offer more supportive features for this population.

In a report titled “Banking for All,” the Yale researchers offer three specific recommendations for features that could help people with mental health disabilities to manage their money. Customizable mobile notifications, self-imposed spending limits on debit and credit cards, and view-only account access for trusted third parties would help them to manage their finances while also retaining some independence.

“The options that are currently available to people tend to be either/or. You’re either left alone to control your own money or somebody else controls your money entirely,” said Annie Harper, a researcher and cultural anthropologist in Yale’s psychiatry department.

But mental health disorders are seldom static, Harper said. Some people dealing with a mental health disability may need to relinquish control of their finances, but many more would benefit from some supportive features that help them to monitor and control their spending.

Harper and her team interviewed dozens of people who either had a representative payee or had been appointed one for somebody else. That research, funded by a grant from the Center for Retirement Research, built upon previous work she had done trying to better understand the challenges that people with mental health issues face in managing their money.

When done well, the representative payee can be a good option for those who truly cannot manage their finances independently, she said. But it can also cause anxiety for the people having their money managed, create tension between the two parties and strain relationships, and can sometimes set a person up for financial exploitation. It can also be stressful for the representative payee, Harper said.

The Yale researchers are not advocating for a new legal designation indicating a person with a mental health disability needs some level of assistance. Rather, they want to see financial institutions adopt supportive tools that can help a person manage their finances as independently as possible.

“Currently, if you have a little bit of trouble managing your money, or a lot of trouble sometimes, there aren’t good tools, either legal or statutory tools, or market-provided tools at most banks,” said Anika Singh Lemar, a professor at Yale Law School.

To be certain, there is a cost associated with implementing any new technology, but the Yale researchers believe many banks and credit unions could feasibly offer these tools. In some cases, it could be achieved by modifying existing technology or marketing certain products or services as being helpful for people struggling with mental health issues.

Many banks already offer mobile notifications, for instance, but Harper said greater detail in those alerts would be helpful for people dealing with mental health disability. One example might be alerts for heavy spending in particular categories that a person already knows they struggle with.

View-only account access would benefit people who want to designate a third party to monitor their bank account for any signs of erratic spending or fraud.

Some banks, including Wells Fargo and TD Bank, already offer that option, but in many cases, a customer has to get a power of attorney to set up the view-only option. Sometimes that feature is marketed mainly for elderly people or customers with physical disabilities, so it may also be the case that many banks simply have not yet made the connection with mental health.

Singh Lemar said that many banks offer a view-only option to their commercial clients and could simply adapt it for retail customers.

Self-imposed spending limits are far less common, but at least two fintech firms, True Link and Greenlight, give customers that option. True Link, based in San Francisco, offers a debit card that allows a third party, like a representative payee, conservator or sober coach, to establish detailed spending limits.

True Link does not disclose the number of people who use its service, but says it includes people dealing with mental health disabilities, substance abuse problems and gambling addictions, as well as elderly customers.

CEO Kai Stinchcombe founded the company because his grandmother suffered from Alzheimer’s disease and his mother struggled to find a banking option that would still allow her some degree of independence.

The person entrusted to handle the card can set limits in different spending categories, on cash withdrawals or even on the times of day transactions are permitted. The cardholder then needs to talk to that trusted third party to ease any of those restrictions.

“The point is not to let your brother run your life, but that actually the right roadblock is not a technical one but a human one,” Stinchcombe said.

Although the Yale researchers focused on people with mental health disabilities, they are quick to point out that those supportive features could be equally helpful for many others, too. Elderly customers, parents of teenagers, and people with substance abuse issues or gambling addiction could also benefit from having these options.

Harper likens them to curb cuts, which were originally intended for people using wheelchairs, but have also benefited parents pushing strollers, people with vision problems, bicycle riders and many pedestrians.

And Singh Lemar said that financial institutions should also think about these kinds of supportive tools as a competitive advantage.

“It’s a set of tools that would happen to benefit people with certain kinds of mental illness, but the benefits are not limited to them,” she said. “I think the banks that choose to get into this space will profit from it.”

The broader social impacts are just as important as the bottom line, the researchers said. People dealing with mental health issues often tend to have less financial stability, and offering them extra support could bring an often overlooked population into the mainstream banking system.

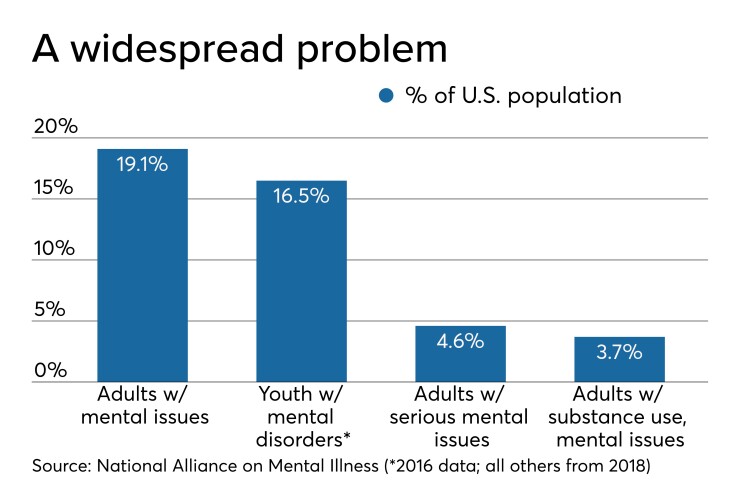

And by offering these tools and talking about whom they can benefit and why, banks and credit unions can do their own part to help destigmatize mental health disorders. The National Alliance on Mental Illness estimates that 48 million Americans deal with a mental health issue at some point in their lives.

“This is a population who already suffer unnecessarily because of the inadequate benefits that we provide them with,” Harper said. “To have a banking system that neglects them on top of that, it has to change.”