StonehamBank in Massachusetts recently began checking in with newer hires around the first anniversary of their start date.

A human resources staffer chats with the employee to assess what’s going well, what could be better, and what other roles the person might be interested in trying. The $687 million-asset bank had previously gleaned a lot of this information from exit interviews with departing or retiring employees. So the thinking was: wouldn’t it make sense to ask current workers the same questions?

StonehamBank, which is based in the Boston suburbs, hopes not only to improve employee retention and engagement, but also to cultivate the next generation of leaders. CEO Ed Doherty recalled that his predecessor, now-board chair Janice Houghton, wore every hat in the bank over her 50-year career. For his own part, Doherty worked in commercial banking, sales and marketing prior to his tenure as CEO. He wants the next generation of community bankers to be similarly well-rounded.

“My boss always embedded in us that you’re training your team to take your job,” he said. “We want people underneath us to want to work hard and move up to where we are now.”

Faced with a rapidly graying workforce, banks are identifying promising talent early, considering less traditional backgrounds in job candidates and finding ways to delay full retirements by employees who have strong institutional knowledge. The entire U.S. workforce is in the midst of a significant demographic shift, but many bankers believe that the financial industry, which struggled to recruit in the wake of the 2008 crisis, will be especially hard hit by the coming retirement wave.

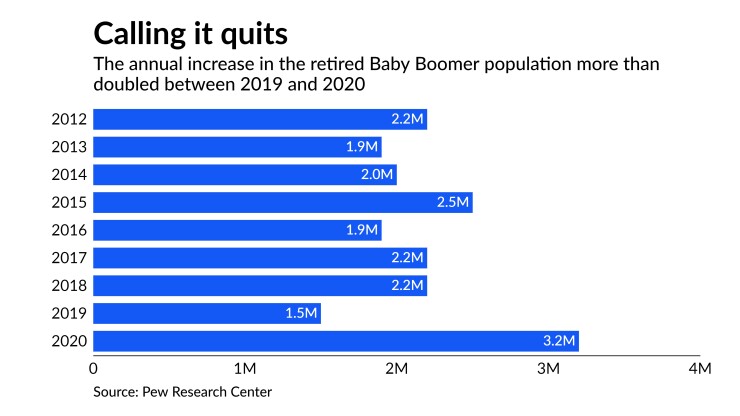

In the short term, COVID-19 has shortened some workers’ retirement timelines. But the real challenge for banks is still ahead, as baby boomers retire with fewer members of Generation X to replace them.

“We've known this is happening in the industry. It’s just the pandemic has maybe expedited things a bit,” said Eric Pikus, head of North America global financial services at the recruiting firm Korn Ferry. “You’ve got a lot of younger talent that’s going to be exposed to a lot more. It puts a lot of emphasis on succession planning and training.”

Retirements compound banking’s image problem

Over the last decade, recruiting has been a challenge for many banks — partly because of the 2008 financial crisis and partly because of competition from other sectors like fintech.

“I think this became an industry that was not really a desirable path for college grads,” Doherty said. “As time prolonged, you had people staying longer because succession planning got difficult to put together.”

That’s now being compounded by demographic shifts that have been a long time coming. By the third quarter of 2021, around half of adults 55 and older had left the U.S. workforce, citing retirement as their reason. Since 2011, the number of retired baby boomers has grown by roughly 2 million per year, according to the Pew Research Center.

It’s not clear that many of the most recent retirees will return to the workforce post-pandemic. Unlike the recession that followed the global financial crisis, solid real estate values and stock market returns have given at least some people the financial confidence to stop working for good.

Bankers and executive recruiters described a relatively small number of retirements that may have already been motivated at least partially by the COVID-19 pandemic. In some cases, senior-level executives simply decided they had made enough money and would rather retire than work through the pandemic. For some, family and health issues factored into the decision.

“I’d say right at the beginning of COVID, we did see some unanticipated retirements,” said Susan Pardus, a partner with KLR Executive Search Group.

Other senior-level executives have left the industry to pursue a second act elsewhere, said Mary Caroline Tillman, co-head of the global financial services practice at the search firm Russell Reynolds. The strong performance of the stock market has given those executives the confidence to try a new career path.

“We track in banking the number of people who move at the senior levels. And this is the highest level of movement that we have seen since the financial crisis,” Tillman said. “They’ve gone to fintech startups, to biotech companies, to some of their clients. They’ve gone into, maybe, venture capital, they’ve gone to" special purpose acquisition companies.

“Some of these bankers are saying, 'If I don’t do it now, then I might not get the chance again for a very, very long time.' "

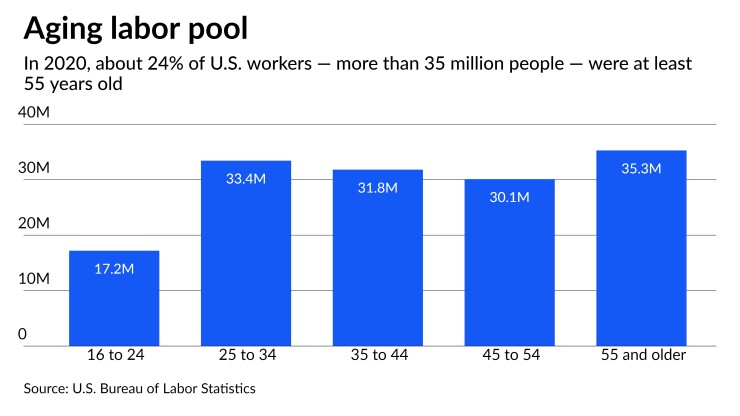

Many more retirements are coming. As of 2020, roughly 24% of all U.S. workers were 55 or older, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In some cases, flexible work arrangements are allowing banks to keep certain senior-level executives longer than they might otherwise. Some community banks, including Ledyard National Bank in Hanover, New Hampshire, and Peoples State Bank in Wausau, Wisconsin,

Seeking to draw on retiring executives’ institutional knowledge for a bit longer, banks have been offering them more flexible schedules and new advisory roles, Pikus of Korn Ferry said.

“There’s a lot of that creativity around trying to get certain individuals to extend and provide their expertise as they’ve begun to retire a little more aggressively,” he said.

Banks turn to nontraditional recruiting

Roughly 40% of the workers at Chelsea Groton Bank in Groton, Connecticut, are over 50 years old, and around 15% are over 60. Chief Operating Officer Tony Joyce says those demographics are “probably pretty typical” for a savings bank, particularly one based in the Northeast U.S.

Anticipating a number of retirements in the years to come, the $1.5 billion-asset bank has been taking steps to better prepare some of its younger bankers as potential succession candidates, Joyce said. Those bankers may get the opportunity to serve on committees or be moved into new roles to gain broader experience, he said.

“We see it as a chance to start to develop [new talent] while we still have some time,” Joyce said, “so we do have people ready to step into those shoes.”

While demographic changes are playing out broadly, some bankers say that certain job functions are being hit harder than others. For example, experienced commercial bankers have long been in short supply, said Cameron Boyd, a partner at Smith & Wilkinson, a search firm in Scarborough, Maine.

The dearth of commercial bankers is a familiar story in the industry. In prior generations, big banks hired scores of new college graduates into in-house commercial credit training programs. But many banks later eliminated those programs, particularly during the recession of the early 1990s. Today, bankers who got their start in that largely obsolete system are planning their retirements.

Yet the demand for seasoned commercial lenders remains strong, particularly given the push across the banking industry to juice commercial loan growth.

“You’ve got this real fundamental supply and demand issue, and it’s the reason that banks are quite candidly overpaying for commercial talent. Because they have to,” Boyd said.

Some banks have begun to revive in-house commercial credit training, while industry associations, including the American Bankers Association and the Risk Management Association, have rolled out similar training programs.

But bankers will need to also fish from a broader and more diverse pool if they want to solve their talent woes in the long term, said Jeff Korzenik, chief investment strategist at Fifth Third Bancorp in Cincinnati. The U.S. fertility rate has been declining over the long term, and firms of all kinds will need to learn to do more with less, and to find talent in new places, Korzenik said.

“This means we have to look everywhere, and there’s some really ripe areas for attracting talent: women who’ve left the workforce to raise children, people who’ve been marginalized by poverty,” said Korzenik, who has written a book about hiring previously incarcerated people. “Banks need as much talent as they can get.”

The industry has already taken some steps in that direction. JPMorgan Chase, for example, has

However a bank chooses to recruit a less traditional labor pool, it’s critical that members of its executive leadership team provide support to its human resources staffers, Korzenik said.

“If they’re responsible for someone who turns into a bad hire, and that person was a nontraditional hire, they often bear the blame,” Korzenik said. “They don’t get enough upside to their careers from experimenting and reaching deeper, so that’s where executive management of any institution has to make sure they are backing these efforts.”