A phishing scam at a small Virginia bank shows how easy it is to fall prey to a cyberattack.

Southern National Bancorp of Virginia in McLean disclosed in its quarterly filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission that it suffered an attack from a malicious email. The scam gave outsiders access to personal information tied to an undisclosed number of customers. It led also to about $172,000 in fraudulent wire transactions.

The $2.6 billion-asset holding company for Sonabank said in Thursday’s filing that the breach occurred in July, adding that it “took immediate action to contain and eradicate” the issue. “We believe this was an isolated event and do not believe our technology systems have been compromised,” the company said.

Southern National executives did not respond to a request for additional comment.

While large organizations garner the biggest headlines for cyberattacks, Southern National's breach drives home community banks' struggle to keep client data and accounts safe.

“Banks are attacked daily, sometimes hundreds or thousands of times,” said James Chessen, executive vice president of the American Bankers Association’s Center for Payments and Cybersecurity. “There’s this constant battle, with hacktivists, hostile nations or whomever trying to get access to information or work their way into a bank.”

While banks have stopped $11 billion of potential fraud in the last year, the threat posed by cyberattacks still looms large, Chessen said. “It’s like a game of cat and mouse. Banks try to be right 100% of the time. Criminals only have to be right once in 10,000 tries.”

While big institutions such as JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup have been hit by attacks that compromised customer data and led in monetary losses, community banks and credit unions are also prime targets because they have limited resources to combat the problem, said Cedric Leighton, a retired Air Force colonel and cybersecurity consultant.

“All I need to do is find a bank that perhaps has some deficiencies in its IT practices,” Leighton said. “I go through that bank and I can skim off a few dollars from a few accounts and it won’t be noticed for a while.”

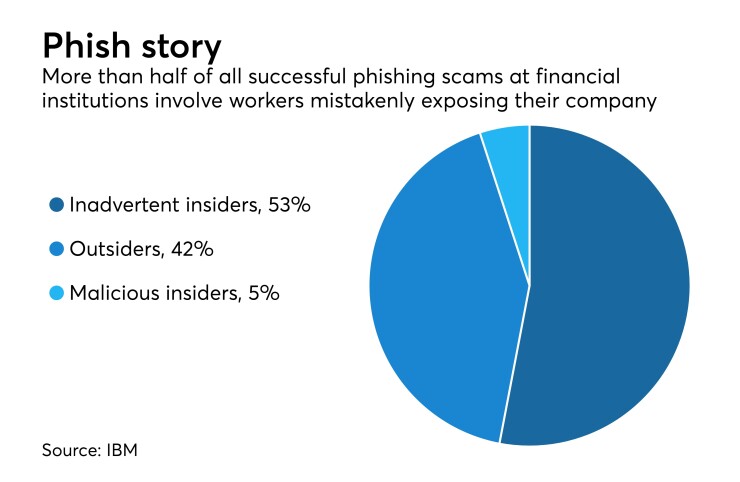

More than half of the phishing scams at financial institutions are tied to “inadvertent actors,” or instances where an employee unknowingly opened his company up to a cyberattack, a study by IBM concluded. Across all U.S. industries, one in roughly 2,000 emails received in June was tied to a phishing scam, according to research by Symantec.

Phishing scams “are still the most common attack vector that hackers use to get into anybody’s email system,” Leighton said. “It’s a 21st-century problem that people and organizations are just learning how to cope with.”

The $490 million-asset Capital Bank of New Jersey in Vineland is so concerned about phishing that CEO David Hanrahan has his IT staff periodically send “spoof” emails to make sure employees stay alert. Incidences of what Hanrahan terms “mistaken clicks” have dropped markedly since Capital began sending the emails, though he realizes the bank is still just one wrong choice away from being compromised.

“I’m very proud of our people, but we’re all human and we’re all prone to error,” Hanrahan said. “It’s something that we have to remain vigilant about.”

Mastercard has turned to its employees for help, Ron Green, the company’s chief information security officer, said during a recent conference hosted by the Federal Reserve and the Conference of State Bank Supervisors.

Mastercard has a program that urges employees to turn in suspicious emails. Points are awarded based on the seriousness of the threat uncovered, and those who collect the most points are eligible for a $2,000 bonus.

In addition to those efforts, banks could consider technical solutions that “sanitize” the email attachments hackers use to breach systems, Leighton said.

Roughly a fifth of all phishing scams in the United States are disguised as invoices, according to Symantec. Another 13% involve documents.

Bankers would be open-minded about any solution that prevents cyberattacks, industry observers said.

“Community bank CEOs take this issue very seriously,” Hanrahan said. “We spend a bundle of money on state-of-the-art technology. More than that, we spend a lot of time training employees and educating customers. That’s because very often humans are the weak link who unwittingly allow a phishing attack to be successful.”

“Protecting against cybercriminals is a top priority in banks,” Chessen said. “They know that customers count on banks to protect their information and accounts. Preserving that trust is a top priority of any institution — large or small.”