The coronavirus delayed, and nearly derailed, a big merger of New York banks.

Dime Community Bancshares in Brooklyn and Bridge Bancorp in Bridgehampton were in the homestretch of negotiating their

Instead of endorsing the deal, Bridge’s board decided at its April 1 meeting that, given the “economic and market downturn” tied to the coronavirus, “it was not the appropriate time to enter into” a transaction, according to a

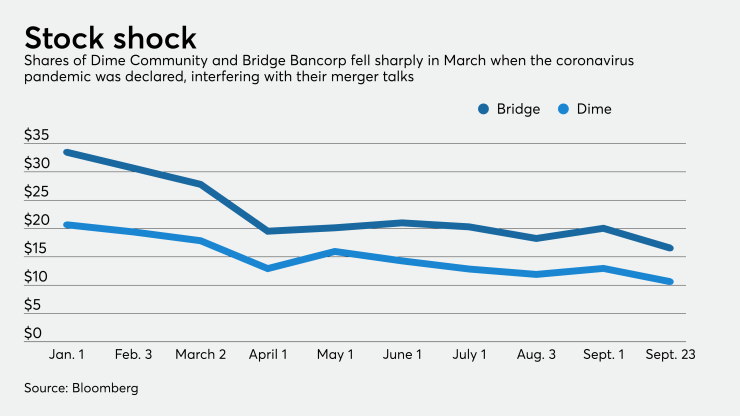

A sharp decline in Bridge’s stock price also skewed the proposed exchange ratio so much that it threatened the deal’s earnings accretion, prompting the two sides to formally end talks in late May. An improvement in Bridge’s stock price in early summer adjusted the math enough to bring the parties back to the table.

The two sides eventually agreed to a merger of equals in July, but the ups and downs of the negotiations outlined in the filing show the delicate nature of trying to structure a merger in the middle of a pandemic.

Several announced deals — including the proposed mergers of

A big reason Dime-Bridge came together, beyond a modest rebound in bank stocks, was the constant communication between the companies. Most of the deal’s terms were locked down pre-pandemic, and executives kept one another informed about coronavirus response efforts.

The first discussion about a merger took place in mid-December, when Kenneth Mahon, Dime’s CEO, met Kevin O’Connor, Bridge’s president and CEO, for dinner.

They determined at that meeting that their companies had complementary balance sheets — Bridge is a big commercial real estate lender while

The process took off from there and the parties quickly made progress.

Bridge’s board created a special committee on Dec. 20 that included Marcia Hefter, the company’s chairman, and Mathew Lindenbaum, an activist investor who had

During a Jan. 16 meeting, Mahon and O’Connor sketched out the framework for a proposed merger of equals that would have evenly divided board representation and featured key executives from both companies. But Mahon expressed his board’s desire to keep “the iconic Dime brand name,” the filing said. Dime Savings Bank of Williamsburg, a predecessor, was formed in June 1864.

Mahon and O’Connor put more of the pieces together on Feb. 5, covering topics such as corporate governance and the company’s reporting structure. They discussed having Mahon serve as executive chairman with O’Connor as CEO. The headquarters and key operational centers were discussed two days later.

By Feb. 10, the executives had filled all the high-level executive posts, identifying officers from both companies. The two sides quickly worked out a plan involving a fixed exchange ratio and exclusive negotiations. An initial draft of the merger agreement changed hands on March 6.

Bridge’s board on voted March 11 to meet on April 1 with an intention to approve the deal.

But the coronavirus began making its way into conversations. Bridge’s special committee discussed COVID-19 during a March 13 meeting, and the topic came up when Dime’s board met two days later. Executives also began to exchange information about coronavirus response efforts.

Both companies were also monitoring fluctuations in their stock prices.

Still, Bridge’s compensation committee on March 31 approved employment contracts for top executives. Dime was set to approve a separation agreement with Mahon, making him eligible for severance.

Market volatility began to complicate the financial considerations. Bridge’s stock fell by 24% between Feb. 27 and March 31, outpacing a 21% decline in Dime’s stock. As a result, the exchange ratio increased to 0.648 shares of Bridge stock, cutting into the deal’s projected earnings accretion.

Coronavirus dominated Bridge’s April 1 board meeting even though due diligence was “substantially completed” and the terms of the merger agreement “had been negotiated to both parties’ satisfaction,” the filing said.

“Before any conclusion was reached as to an appropriate exchange ratio, the discussion turned to the current situation in the New York metropolitan area” tied to the pandemic. “It was noted that the pandemic had yet to peak in the New York area in terms of cases, fatalities and the economic fallout.”

So Bridge’s directors had O’Connor contact Dime to tell it that, while the board endorsed the transaction, “now was not the right time to proceed,” the filing added.

During the pause, executives stayed in touch, monitoring pandemic responses and the potential exchange ratio. The ratio remained elevated, weakening the chances of working out an acceptable transaction.

Though the companies agreed to extend the exclusivity period to consider an “acceptable” exchange ratio, they failed to find middle ground and officially terminated negotiations on May 29.

Just two weeks passed before the companies decided to reengage.

By June 15, Bridge’s stock had improved “both in absolute terms and relative to the improvement in Dime’s stock price,” bringing the exchange ratio back “within an acceptable range,” the filing said.

Mahon made it clear that Dime wanted the same 0.648 exchange ratio that had been discussed on March 31, subject to an updated loan review and due diligence. Bridge’s special committee backed those terms, and the companies targeted July 1 for signing a merger agreement.

When the revised merger agreement was reviewed in late June, there were “no material changes” from the terms reached on April 1, the filing said. The final round of due diligence took place over the last week of June, covering loan deferments, pandemic-related loan exposures and each bank’s portfolio of Paycheck Protection Program loans.

The boards unanimously approved the merger on July 1; it was announced the next day with an expected close in the first quarter. The deal, with Bridge as the legal acquirer, valued Dime at 97% of its tangible book value.

The headquarters will be moved in Hauppauge, N.Y., with a corporate office in New York. The combined company, which will retain the Dime brand, will have 66 branches, $11 billion of assets and $8 billion of deposits.

The deal is expected to be 7% accretive to the company’s earnings per share. It should be 0.4% accretive to its tangible book value.

The plan is to cut about 15% of the combined company’s annual noninterest expenses, or roughly $32 million, largely by renegotiating vendor contracts and reducing technology costs. The companies expect to incur $60 million in merger-related expenses.

The merger “will allow us to build on our complementary strengths and provide significant value for shareholders,” O’Connor said in a release announcing the deal.

“Our enhanced branch footprint and increased capital base will allow us to better serve the needs of our customers,” O’Connor added. “Both companies have strong balance sheets and demonstrated histories of low loan losses … which give me confidence that we will be well-positioned to succeed in any environment.”