John Mackey has written a

Mackey filled the book with stories and anecdotes, including one recounting how a community bank in Austin, Texas, Whole Foods' home town, along with a true-believing loan officer provided a critically needed loan that propped the company up in the grim aftermath of a catastrophic flood.

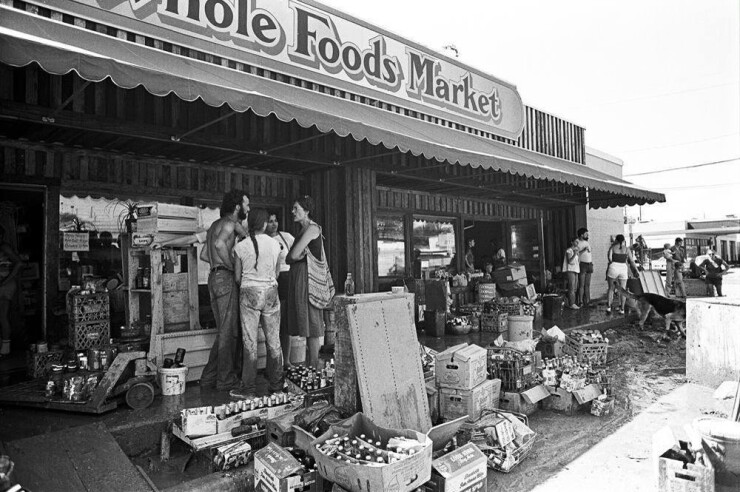

Whole Foods was less than a year old in May 1981, when a devastating Memorial Day storm flooded its sole store on Lamar Boulevard. Torrents of rainwater spoiled an estimated $400,000 worth of inventory. Ivan Sheppard, who worked as a programmer at Whole Foods' lender, the Austin-based City National Bank, recalled the store was situated on a "kind of low point" on Lamar Boulevard, making it especially vulnerable.

"They had all the inventory pulled out in the parking lot," Sheppard recalled. "It was bad."

Making matters existentially worse, Whole Foods' insurance policy didn't cover flooding.

Seemingly every Austinite old enough to have lived through it recalls the Memorial Day storm. Mackey describes it in dramatic detail in "The Whole Story," the rain, losing power, the water cascading down Lamar Boulevard. A major storm had been forecast. Mackey and other employees had surrounded the store with sandbags, but they were overwhelmed, leaving the crew to survey the wreckage.

"As I stared at the soggy remains of Whole Foods Market, I felt much older than my 27 years," Mackey writes. "It wasn't immediately clear we could recover from this."

Certainly, few in Austin would have bet much on the company's survival, much less its future growth prospects. "I remember [driving past Whole Foods] in the early days and saying this is just another bunch of Hippies with a health food store," Sheppard said. "'They were all over the place in Austin. This [seemed like] just another one."

Thanks to a doughty group of employees and volunteers who cleaned the store, as well as suppliers who agreed to finance new groceries to replace the ruined stock, Whole Foods did recover. But the company's cash was exhausted. "We still had a great business with loyal customers, but without insurance there was no capital to get us back on our feet," Mackey writes in the book.

In his hour of need, Mackey turned to City National.

Mackey summarizes the episode this way in the "The Whole Story.": "I explained the situation to Mark Monroe, [our] local banker. To my surprise, he was receptive and friendly. After a couple of meetings, he told me the bank had agreed to a $100,000 loan. I was thrilled. I could hardly believe they'd asked for nothing more than my signature."

Back in business by late June of 1981, Whole Foods grew rapidly. "We just kind of took up right where we left off," Mackey said in an interview with American Banker. "It didn't take us long to [settle] that loan. We repaid it within a few years."

His company back on solid footing and his attention consumed by the demands of a growing, increasingly profitable business, Mackey moved on. As "The Whole Story" relates, Mackey battled critics inside and outside the company, pursuing growth with evangelical fervor. Whole Foods expanded in Texas and California, then from coast to coast following its 1992 initial public offering. Along the way, Whole Foods changed the way grocery stores operated, pioneering the introduction of fresher, healthier, higher-quality meat and produce, now standard operating procedure industrywide.

One of the book's most compelling subplots revolves around the role Mackey's father played. Bill Mackey, an accountant, teacher and health care executive, provided seed capital and vital advice and counsel during Mackey's first two decades as CEO. "I leaned really heavily on him," Mackey said in the interview. "He was my mentor for my first 16 years in business, until I got to be 40."

Ironically, one of Bill Mackey's first pieces of advice may have paid huge dividends in the aftermath of the Memorial Day storm. About a year earlier, the elder Mackey had advised his son to take out a small loan in order to establish credit.

"He was very strategic" about building a relationship with the bank, Mackey said. "Borrow the money, make the payments on time, show that you're reliable. You're going to want to ask them for more money down the road. I would have never thought to do that."

An unexpected turn

Around 2014, a chance meeting with a former City First employee at an industry conference jolted Mackey's memory about the long-forgotten $100,000 loan. The ex-employee, whom Mackey does not identify, brought up the transaction. "That was quite a thing Mark Monroe did for you after that big flood," Mackey, in "The Whole Story," recalls the man saying. Mackey concurred, confessing his surprise City National had agreed to lend such a substantial sum requiring nothing more than his signature.

"He looked puzzled," Mackey writes. "The bank didn't approve that loan. The bank turned it down. Mark Monroe personally guaranteed that loan for you. That's the only reason you got the money."

The revelation floored Mackey, who wrote that his immediate instinct was to contact Monroe to thank him. Unfortunately, the ex-employee said Monroe had died a few years earlier.

"So many acts of generosity and good faith have helped Whole Foods Market survive and grow over the years. Amid the pantheon of contributors to our success, I reserve a special place for Mark Monroe," Mackey writes in the book.

Whole Foods Market "might have squeaked by," without the City National loan, Mackey said in the interview with American Banker. "It's hard to say. We might have just tightened our belts." The money "sure made it easier for us," Mackey added quickly. "There's no question [the relationship with City National] helped Whole Foods."

Mackey's assessment is "undoubtedly true," Ed Piner, who headed City National's operations department, said in an interview. "I just know how tough the situation was," Piner said. "It probably would have been very, very tough for them to survive."

The rest of the story

Among former employees of City National, which was acquired by Houston-based FirstCity Bancorp of Texas, the bank's relationship with Whole Foods and the 1981 loan remain a point of pride.

City National was founded in 1936. It was never Austin's largest bank, but it inspired great loyalty among clients and employees. Steve Scurlock, son of City National President John Scurlock, said some of his best childhood memories are of visiting borrowers on drives with his father. "He'd kind of pull off the way we were going and stop at a restaurant, a little boat manufacturer, car dealership, whatever it was, and drop in to say hi," Scurlock said. "The banking world was literally one of the last bastions of the good old days. Things were literally done on a handshake."

Scurlock definitely recalled Whole Foods. "It was one of their customers, and it was not the remarkably successful, super-cool [operation] it became. It was just a very small, bootstrap business on North Lamar in Austin," Scurlock, who recently retired from the Independent Bankers Association of Texas, where he served as director of government relations from 1995 to 2023, said. "That was one of the ones I think that intrigued [John Scurlock]."

"I remember fondly the knowledge of how that significantly helped Whole Foods," Piner said about the loan. "I remember the fact that the bank really went out on a limb for them."

Though neither Scurlock nor Piner could say whether Monroe offered to personally guarantee the loan, Piner said someone at the bank must have gone above and beyond to sell senior management on the idea of lending to Whole Foods. "I know John Scurlock [and] John Burns, who was chairman, had to have been convinced to be able to make that loan," Piner said. "Somebody did a very good job of helping them to make that decision. It was a wonderful decision as far as [Whole Foods] was concerned."

"I think [Mark Monroe] was the lending officer that had to try to convince management we should do this," Piner added. "He must have really dug deep to sell management."

Interestingly, Monroe, the central character in all this, did not pass away. He is alive and working in his second career. Retiring in 2003 after a 30-year career in banking, Monroe earned a degree in counseling and pastoral ministry. He began a career as a licensed professional counselor. He practices quietly in San Antonio. Monroe's father did pass in 2014, which may explain the confusion on the part of the ex-employee who spoke to Mackey.

Citing confidentially, Monroe flatly refused to discuss the loan to Whole Foods, beyond acknowledging that he worked at City National in 1981 and was familiar with both Mackey and Whole Foods. Monroe said he considered privacy to be a hallmark of banking professionalism, adding his commitment to confidentiality has only deepened as a result of his two decades in counseling. Informed of Mackey's complementary account in "The Whole Story," Monroe said it "sounds like John Mackey. … The attitude of kindness and gratitude were characteristic of his personality."

For his part, Mackey still expresses astonishment at the loan as well as the role Monroe played. "I think Mark Monroe took a calculated risk the bank didn't want to take," Mackey said.

Mackey presided over Whole Foods' $13.7 billion sale to Amazon in 2017. He retired as CEO in September 2022.