Bankers are finally able to put to good use a secret weapon they’ve had hidden away for years — piles and piles of cheap deposits.

Three rate increases from the Federal Reserve since December 2015 have allowed banks at last to generate meaningful profits from spread income. That’s because loan books stuffed with floating-rate loans tied to short-term rates like Libor have repriced at higher rates while banks have done virtually nothing to raise rates on deposits.

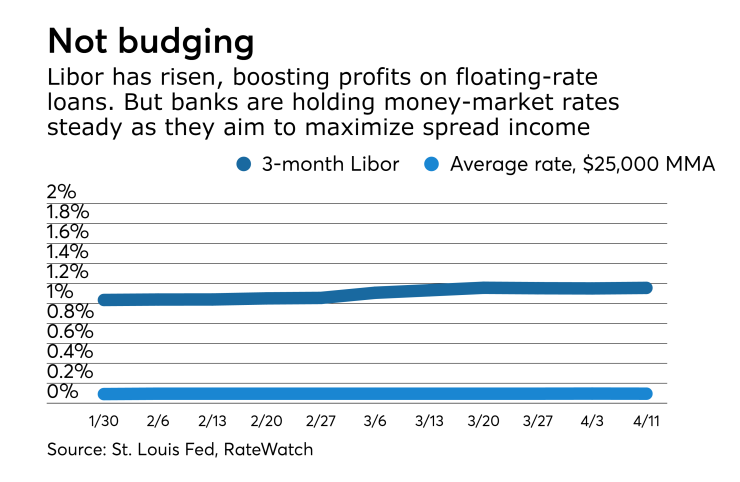

Consider that Libor, the London interbank offered rate, has risen from 1.04% on Feb. 6 to 1.15% on April 11, according to the St. Louis Fed. In the same period, the average rate on a $25,000 money-market account remained at 0.095%, according to RateWatch, and average rate on a 12-month, $10,000 certificate of deposit had only increased from 0.223% to 0.235%.

Banks want to hold the line on raising deposits at least until spreads widen just a bit more, said Marty Mosby, an analyst at Vining Sparks. Once the bulk of their adjustable loans have repriced, banks can raise deposit pricing enough to appease customers without giving up spread income, he said. Some may go ahead and start raising deposit prices this quarter, while others are likely to wait until later in the year.

Through Monday, the average net interest margin for the roughly 1,400 banks that had filed call reports for the first quarter was 3.52% — up from 3.10% in the fourth quarter, according to BankRegData.com.

This long-awaited spike in net interest margins should bode well for bank stocks, though Mosby said that interest rates have been so low for so long that investors had pretty much stopped factoring the value of the deposit franchise into their calculation for determining a stock’s value.

“The asset side, everybody understands that piece. Nobody really understands the deposit side,” Mosby said.

Mosby said that over the last several years, investors have paid too much attention to the trajectory on the benchmark 10-year Treasury because they viewed it as a proxy for the overall direction of rates.

Now the market has moved to a new phase of the recovery and the 10-year Treasury has less relevance to bank stocks because banks’ floating-rate loans are tied to Libor, not the 10-year, he said.

The key is that banks keep a lid on deposit costs for as long as possible, to take advantage of repricing loans. So far, that seems to be happening. That concept, in the industry parlance, is referred to as “deposit betas” and virtually every bank has been asked about its deposit betas during this quarter’s round of conference calls.

“With a beta of less than 10% for total interest-bearing deposits … we maintained our deposit pricing discipline despite the increase in interest rates,” Don Kimble, the chief financial officer at the $135 billion-asset KeyCorp in Cleveland, said during an April 20 conference call.

The lower the deposit beta, the better, because it means the bank’s deposit pricing has remained flat while loan rates have increased. The goal is to keep the deposit beta low for as long as possible.

Kimble noted that KeyCorp’s deposit beta should remain low for the rest of this year. That means KeyBank likely won’t reward its customers with higher deposit rates until 2018.

KeyCorp’s earnings

Other banks have reported higher deposit betas. The $28 billion-asset First Horizon in Memphis ran some deposit promotions at its First Tennessee Bank during the first quarter, leading to a 40% deposit beta, according to a research note from Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. The cost of its interest-bearing deposits during the first quarter climbed 10 basis points to 0.39% from the previous quarter.

However, First Tennessee deposit promotions will only carry a higher rate for six months, Chief Financial Officer BJ Losch said. So the increase will only affect a small part of the deposit portfolio, limiting the negative impact on the deposit beta.

It’s just a way “to build [deposit] balances,” Losch said.

Some banks are expected to benefit more than others in the new deposit environment. The $100 billion-asset Huntington Bancshares in Columbus, Ohio, paid $3.3 billion to acquire FirstMerit in Akron, Ohio. Huntington obtained a huge stash of deposits in that deal, but those deposits haven’t done it much good since loan rates have been so low. That will soon change, Mosby said.

“Huntington deployed a lot of their capital to add all of FirstMerit’s deposits,” Mosby said. “Now they will have an easy layup.”’

In the first quarter, Huntington boasted a 21% yearly rise in net income, to $208 million. Huntington

Other banks that are well positioned to benefit from keeping deposit costs low include the $63 billion-asset Zions Bancorp. in Salt Lake City, which has a high portion of commercial customers that favor immediate access to cash over interest-bearing deposits; and the $125 billion-asset Regions Financial in Birmingham, Ala., which holds many deposits in rural areas with little bank competition and thus less pressure to raise deposit rates.

So far, banks are not feeling pressure to raise rates.

“We haven't really seen any noticeable customer demand or push for higher deposit costs,” David Rosato, the chief financial officer at the $40 billion-asset People’s United Financial in Bridgeport, Conn., said during an April 20 conference call.

Of course, consumers will eventually catch on, and banks will need to start paying up if they want to retain customers. It’s a good idea to gradually raise rates, offering higher prices on only one deposit product at a time, said Neil Stanley, CEO of The CorePoint, who advises community banks on deposit strategies. Banks can also create adjustable-rate deposit products to keep their best customers, he said.

“Instead of paying every customer more, maybe try running a one-off promotion, or try a tiered approach,” Stanley said. “But if you’ve got this option to keep deposits cheaper, you do it for as long as you can.”