It's just after 9:15 outside the House Financial Services Committee hearing room in Washington, and a group of about 20 activists unfold a large, yellow banner with the words "FED UP" painted in bold red letters across the front.

The protestors are there ahead of a hearing on the governance structure of the Federal Reserve System and they want their point of view to be heard.

"In just a few minutes, two of the most hawkish Federal Reserve presidents are going to try to defend the way things work now," says Ruben Lucio, field manager for the Fed Up campaign. He's positioned in front of the banner and speaking to a man who is filming the scene on his iPhone.

"They will try to convince you that the status quo – one that excludes low-income communities and communities of color from the monetary policy conversation – is working," Lucio says. "I'm sure it's working, but for whom? White, male corporate bankers? Is that right?"

The two regional Fed bank leaders who'll be testifying before the panel on this morning are Richmond Fed president Jeffrey Lacker and Kansas City Fed President Esther George.

But George is not the obvious choice as a defender of the Fed's status quo. Indeed, she is seen as an outsider in that system. In her capacity as a voting member on the Fed's Federal Open Market Committee, she has departed from the majority 10 of the 13 times she has cast a vote as of July, routinely calling for rates to go up as the rest of the committee opts to keep them at or around zero.

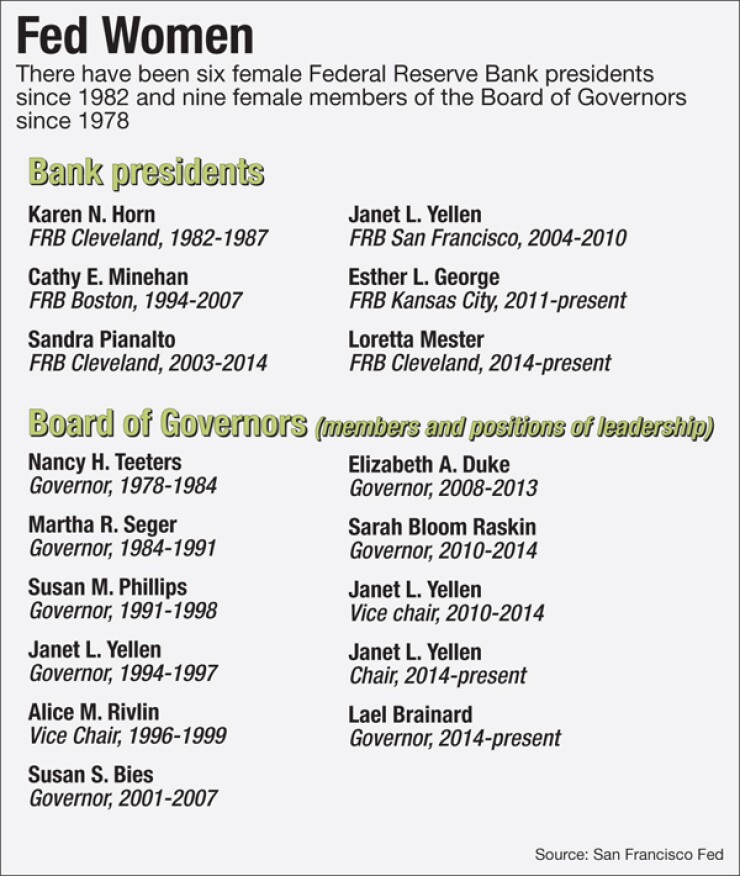

Her career and background are not typical for a regional Federal Reserve Bank president, either. She is one of only two women, along with Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester, to head a regional Fed bank, and one of the relatively few women ever to have either headed a regional bank or serve as a member of the Board of Governors in over 100 years. She is also a career staffer in a system that draws heavily from the banking industry and academia. She represents a section of the western plains in which she not only grew up but where her family goes back generations.

Yet speaking before the committee roughly an hour later, she calmly and methodically defended the system. The creators of the Fed settled on a federated, decentralized structure precisely because of public skepticism about a central bank – a wariness that killed the first two central banks in the 19th century and that dog the system to this day. Changing the Fed would only weaken it, she said.

"The Federal Reserve's unique public/private structure reflects these strongly held views and is designed to provide a system of checks and balances," George said. "Altering this public/private structure in favor of a fully public construct diminishes these defining characteristics, in my view. It also risks putting more distance between Main Street and the nation's central bank."

George grew up in Faucett, a small, unincorporated town in northwest Missouri, on a farm that has been in her family since the mid-1800s. She still raises soy, corn and cattle on the land, though she lives in Kansas City with her family.

She became interested in banking as a teenager when she got her first summer job in a bank, stuffing canceled checks into customers' monthly bank statements, and later working up to being a teller. The contrast with backbreaking farm work attracted her immediately, she said. "If you grow up on a farm, summer jobs aren't fun and they don't pay well – especially when you work for your dad," George said. "So going to the bank, I thought, 'This is great! It's clean. It's cool in the summer. This would be a good place to go.' "

After graduating from Missouri Western State University with a degree in business administration, she initially thought of moving to New York and joining Dun & Bradstreet, a financial data firm. But the company offered her a job in their Kansas City offices instead, cold-calling businesses asking for information about their activities. After a few years, she responded to an ad in the newspaper and joined the Kansas City Fed as a bank examiner in 1982. "I learned a lot making cold calls on people who didn't necessarily want to see me," she said. "At least as a bank examiner, you have a team of people with you."

Her timing was portentous. Just as she was starting her new job, Penn Square – a commercial bank headquartered in Oklahoma City that had swelled to over $500 million in assets in less than 10 years – went under, owing to poor management and gross overleveraging in loans associated with the oil patch boom of the late 1970s. The bank's collapse was the beginning of a wave of failures that would characterize the 1980s, tied partly to the oil glut.

That experience made a deep impression on George, not only because it gave her a sense of purpose in the importance of her work, but because it generated a distrust of the then-prevailing philosophy that the financial industry can be self-regulating.

"I started my career in a part of the bank where you got to see how the economics, how the monetary policy, how the supervision and regulation calibration all fit into the real economy. It was a real education," she said. "It was thought that market discipline would take care of [risk]. That proved not to be the case."

After years as a supervisor, she moved around the organization – going to research, statistics, human resources, briefly to public affairs and then back to head the department of supervision. In June 2009 she was named first vice president of the bank, effective Aug. 1. Almost simultaneously, she was detailed to Washington on a six-week interim basis to act as the head of the Federal Reserve Board's division of supervision.

In 2011, Thomas Hoenig, who had served as president of the Kansas City Fed since 1991, was term-limited out of the job, and a search committee was convened to identify candidates for his replacement. He said he had no doubt who he wanted to succeed him when the panel asked him who his preferred replacement would be.

"They asked me for recommendations ... and of course, knowing the quality of Esther and her skills, I recommended her and gave her a very strong recommendation," Hoenig said. "They chose her and I couldn't be more pleased that they did."

George's interim stint heading the Fed's supervision office gave her a measure of visibility, at least within the central bank. It put her at the table with some of the nation's biggest banks at a pivotal moment in the nation's history. But when she first sat on the FOMC in 2011, some insiders were surprised to see that she had seemingly inherited Hoenig's view that rates needed to rise, and they needed to rise now. She has been one of the lone voices on the FOMC advocating for such action ever since.

Her explanation for dissenting "was almost always concern about the financial stability consequences of very low rates," said one former Fed staffer who asked not to be identified. "I was a little surprised, to be honest, to see her pick up that mantle, because I didn't know she had the same view on the issue as President Hoenig."

The debate over when to raise rates is fundamentally a judgment call about which of two things poses the greater threat to the financial system.

On the one hand, keeping rates at or near zero for too long incentivizes funds that might otherwise be safely deposited in banks – where they are insured – to flow to uninsured, risky investments, such as the stock market. This can create asset bubbles, which increase the potential for another economic shock. And that shock is one which, because interest rates are at zero, the Fed is less prepared to respond.

But the other view – and the one that has largely prevailed on the FOMC – is that there are definite and obvious signals one should look for when normalizing rates after a recession. Those are, specifically, a strong labor market and increasing inflation. Raising rates too quickly, absent those indicators, could slow growth and cause the global economy to go awry.

Hoenig said that he didn't pick George to carry on his vision on the FOMC. But he knows what it's like to be a lone voice, and he said that it takes courage to vote your conscience in the context of what is arguably the most consequential committee on earth.

"I don't call it lonely, but I do call it difficult, because you have to be very confident in your views to go against a majority, even if it's only by one," Hoenig said. "And many who agree with you won't vote with you – they don't want to stand out. That's where I think she has shown a lot of courage."

FOMC minutes suggest that at least some of her colleagues find George's point of view compelling and may even agree with it. Some members during the July meeting expected that conditions "would soon warrant taking another step in removing policy accommodation."

Leading up to the September meeting, several FOMC members – including Lacker and Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren – said they were coming around to George's way of thinking. At the September meeting, George, Mester and Rosengren all voted for a 25-basis-point hike – an uncommonly strong dissent from the majority.

The Federal Reserve – and the FOMC in particular – is a strange place, governed by unspoken rules. Alan Blinder, former vice chairman of the Fed and professor of economics at Princeton University, said there is an internal pressure to conform to the majority – or to at least be judicious with one's dissents – because after a certain point the dissenting vote loses its edge.

"If you have someone who's always dissenting in a hawkish direction – or if you have someone who's always dissenting in a dovish direction – they become part of the background noise," Blinder said. "When you're having the discussion, especially if the decision is difficult and the committee is divided, the centrists would tend to dismiss the extremes, saying 'Oh, there they go again.' If you dissent at every meeting ... the centrists on the committee, and I presume the chair of the committee, kind of expect it."

But George said her goal isn't to change anyone else's mind. She is there to articulate her view based on the data put before her and her staff and the information she gathers from bankers, citizens and businesspeople in her district. If that runs counter to the majority, so be it. But so long as she clearly communicates her reasoning and is open to all sides, she's holding up her obligations as outlined in the bank charter.

"I see myself as trying to be as honest as I can," George said. "I don't see my primary job as convincing others. The burden always falls on those who are the outliers, right? I think the honest thing you have to try to do at that table is not to try to second-guess what the markets think ... but if I can be clear in my public speeches, and if I can be clear when I talk to people about how I think about [monetary policy], then I can be consistent with how I see the issue."

How George sees the issue is in large part a product of how she sees the economy. And that stems in part from the district she represents.

The Kansas City Fed comprises western Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Oklahoma, Colorado and northern New Mexico. That area of the western plains is notable for being dominated by smaller community banks and midsize regionals; a legacy of anti-branching laws that were common in the area. There are no banks headquartered in the district with more than $50 billion in assets – the statutory definition of a systemically important financial institution.

That's an important distinction. Small banks tend to rely on the traditional sources of funds for their activities – customer deposits – while larger banks usually have more diversified sources of funding. Low interest rates hurt banks' ability to attract depositors in a way that disproportionately affects smaller institutions.

Oklahoma State Banking Commissioner Mick Thompson, who has worked with George for more than 20 years, said her background in supervision and community banking may have sensitized her to the challenges that those smaller institutions face in a way that other FOMC members do not share. "A lot of times when you get to the board level, the economists who report to the board have never been in the trenches to see what actually happens in community banks. Unfortunately, not everything in the real world fits within a neat box or computer program," Thompson said. "I think Esther understands what sometimes gets lost if you have not actually been in the small community banks."

Hoenig echoed that observation, saying that George's perspective is shaped by long experience with the inner workings of banks, as opposed to the more academic route that is prevalent on the Fed board. That experience is precisely the kind that a large and diverse committee is intended to include.

"The Federal Reserve is heavily influenced by academics, and they have a very clear, shall we say ... theoretical approach," Hoenig said. "In the end, whether you're in Kansas City or Washington, D.C., or San Francisco or New York, what is best monetary policy for the country has to drive your decisions. And it's in that greater context that I think she acts with experience that is unique in terms of knowledge of how these financial institutions work, what their influence is in terms of economic impact, and the consequences of bad policy as well as good policy."

Jonathan Kemper, chairman of the Kansas City area of Commerce Bank – with assets of $24.5 billion, the largest Fed member bank headquartered in the region – said George's independence to voice that perspective on the FOMC is the beauty of the Fed system. A central bank subject to political pressure would not be free to take actions that are necessary, even if they are unpopular.

"Either you believe in having an independent central bank or you don't," Kemper said. "My personal feeling is that politicians really cannot be trusted with monetary policy; over time they always will choose popularity rather than maintaining a stable currency."

Pam Berneking, president and chief executive of Alterra Bank, a $300 million-asset, Fed-regulated bank based in Kansas, said George's path to the FOMC gave her a depth of knowledge on all sides of tough problems. That instilled in George an instinctual openness to different and conflicting ideas and approaches, Berneking said.

"She just learned to be a real listener," Berneking said. "I think that's unusual – the academic route is more commonplace, and Esther's route is less so. That's one of the reasons she's so valuable in that role, because she does have that depth of understanding of someone who works their way up through the ranks at the bank."

That understanding is appreciated by larger banks as well. Kemper said George's experience and approach is in line with what the framers of the Fed system had in mind when they established the central bank in the first place.

"Esther expresses the original concept of Fed districts being reflections of diverse geographical and industrial perspectives," Kemper said. "Also, from our position as a regional bank, it is essential to us to have someone who understands how banking works and that bank regulators can introduce a huge amount of concern – who understands the responsibility as well as the power they have."

That depth of understanding extends beyond her voice on the FOMC. The Kansas City Fed is a very large organization. In addition to managing the cash supply in its region, it has a robust information technology division, and George – along with Fed Gov. Jerome Powell – is heading a systemwide inquiry to identify ways to improve and modernize the U.S. payments system.

The Fed is also a big wheel in the local Kansas City and regional economies. Bill Dana, president and CEO of Central Bank of Kansas City, a community development financial institution not directly regulated by the Fed, said George puts an emphasis on reaching out to various stakeholders in the community by giving speeches, opening the Fed's doors to host events and engaging in other means of outreach. That has cultivated a kind of soft power in the region that people appreciate and to which they respond.

"The extra mission of being involved in the community ... I don't know where that fits on the Fed list of priorities or even if it is a priority," Dana said. "But it happens, and it happens in spades. Sure, she's required to be the supervisor of these banks and is not afraid to make the tough calls ... but she still has the compassionate heart to be helpful, especially to banks and, in my mind, the folks who are less fortunate."

George says she sees those connections as not only courteous relationship-building but as important conduits of information for the Fed system generally. In the aftermath of the crisis, banks in her district were reeling, she said, and the Kansas City Fed was able to tell those banks about resources and programs that could help them get through the credit crunch. Those institutions were the Fed's eyes and ears on what was happening economically in their communities as well, she said.

"That couldn't have happened in the same way, and in a timely way, if you don't have that connection in these communities," George said. "And the way you get that connection is you get out there. What I'm trying to build is a connection with the institution so that information can flow, so that in a time of crisis I don't have to invent those relationships."