Webster Financial in Waterbury, Conn., doesn't rank among the nation's 50 largest bank holding companies, but it is the industry leader in one fast-growing business line: health savings accounts.

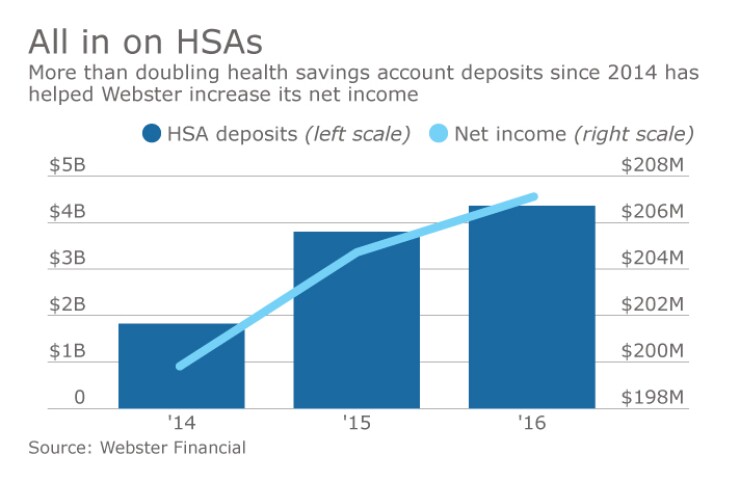

Webster now controls 14% of the $37 billion HSA market — far more than any other bank — thanks to a strategic decision it made in late 2013 to invest more heavily in the business and go after larger accounts. At the time, deposits from its HSA subsidiary were already funding much of Webster's commercial loan growth and further expansion in that business was seen as a way to accelerate its push into new markets and business lines, lower funding costs and boost fee income.

The $26 billion-asset Webster, once a traditional thrift, had begun reinventing itself as a commercial bank in the early 2000s, but its quest to diversify had taken on new urgency following the financial crisis as it grappled with changing customer behavior, slow economic growth in its home state, historically low interest rates and rising regulatory costs.

Though such pressures affect all banks, Jim Smith, Webster's chairman and chief executive, contends that regional banks in the $10 billion-to-$50 billion asset class are feeling particularly squeezed and need to think creatively to remain competitive and deliver strong returns to shareholders.

"We see ourselves as tweeners," said Smith, a former co-chair of the American Bankers Council, a group within the American Bankers Association that represents the interests of midsize banks. "We're not exempt from a lot of the regulations like the banks under $10 billion, and we have the full brunt of the regulations for banks with over $50 billion without having the cost efficiencies they do."

Webster has differentiated itself by prioritizing HSAs, expanding its commercial lending into new markets and developing expertise in business lines like technology, media, telecommunications and health care.

Other "tweeners," like the $28.4 billion-asset First Horizon in Memphis, Tenn., the $21.5 billion-asset TCF Financial in Wayzata, Minn., and the $18.9 billion-asset Bank of the Ozarks in Little Rock, Ark., have made bold moves as well. First Horizon last year bought a restaurant franchise lending business from GE Capital and in recent months has hired teams of bankers with expertise in health care lending, structured equipment finance and lending to the music industry. TCF has largely de-emphasized real estate lending in its traditional markets and built a national footprint in both automobile lending and specialty lending that includes financing dealers of recreational vehicles, boats, lawn and garden equipment and consumer electronics. Bank of the Ozarks has been an active acquirer of small banks in the South, and two years ago it bought a New York bank that gave it a national commercial real estate lending platform.

"Anyone over $10 billion is trying to gain scale to improve profitability and they are trying to find new and different ways to do that," said Mark Fitzgibbon, the director of research and a principal at Sandler O'Neill. "Webster is an example of a company that has found a unique niche where they've become dominant."

For Webster, the investments in the HSA business included major systems upgrades that allowed it to quickly scale up the business and the creation of a multiaccount offering that lets customers access all health accounts — including flexible spending accounts and health reimbursement accounts — from one point of entry. A big break came in 2015, when JPMorgan Chase put its HSA operations up for sale and Webster won the bidding.

"We would never have been able to even bid on that if we hadn't made the decision" to go all in on HSAs, said Chad Wilkins, the president of Webster's HSA Bank unit.

The JPMorgan Chase deal more than doubled the size of Webster's HSA business and set the stage for what Webster projects will be rapid organic growth. Total accounts increased by more than 20% last year, to more than 2 million, and Webster expects the business to grow at a similar pace for each of the next five years. Growth might have come even faster if the Trump administration and Congress had succeed in repealing and replacing the Affordable Care Act, though Smith said he expects that whatever happens with health care policy, HSAs are likely to be seen as part of the solution.

"The fundamentals haven't changed," Smith said, "HSAs are still seen very favorably ... [and] sooner or later the growth rate is likely to accelerate because of their broad acceptance."

That could bode well Webster's long-term strategic plan.

Over the last several years, Webster has opened commercial loan offices in Boston, New York, Providence, R.I., Philadelphia and Washington, and significantly ramped up asset-based-lending operations in Baltimore, Atlanta and Philadelphia. While the bank is hardly abandoning Connecticut, where it has the No. 2 deposit share, its growth plan calls for continued expansion in markets where it is seeing greater demand for commercial loans.

Commercial and commercial real estate loans have increased at an average of 14% annually since 2011 — well above the industry average — and Smith said that "low-cost, long-duration" HSA deposits have funded that growth "almost dollar for dollar." Webster is allocating the bulk of its capital to business lines that are generating the greatest returns and Smith told investors in January that the HSA business is the bank's highest strategic priority.

"Our obsession with the HSA business, and crucially, our commitment to invest in it, have enabled rapid growth and transformation," Smith said on Webster's fourth-quarter earnings call. "It has the potential to generate more economic profit than any other business by far."

In some ways this diversification is also a survival strategy. Unlike banks with less than $10 billion of assets, Webster and its midtier peers are subject to stress tests, examinations from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and, most notably, caps on interchange fees. Larger banks are subject to even more strenuous stress tests, but by and large they have the scale to absorb the hit to interchange fees and the added compliance costs more easily. Plus their deeper pockets allow them to invest more heavily in technology that can improve efficiency and delivery of service over the long term.

Among these smaller regionals, few banks have undergone as thorough a transformation since the financial crisis as TCF.

Craig Dahl, TCF's president and CEO, said that the crisis hit many markets in its footprint hard, so traditional lending opportunities in cities like Chicago, Milwaukee and Detroit became increasingly scarce. Meanwhile, caps on debit interchange fees and new mandates governing banks' overdraft programs — both aimed at protecting consumers — combined to lower TCF's noninterest revenue by an estimated $50 million to $60 million a year, Dahl said.

"The changes to our revenue stream really forced us to look at other revenue sources," said Dahl, explaining the decision to focus on specialty lending.

Such expansion doesn't come cheaply, though. While the focus on specialty lending has helped to lift TCF's net interest margin — it was 4.41% in 2016 — the efficiency ratio has remained elevated even as TCF has shuttered roughly 100 supermarket branches in recent years. Dahl said he expects expenses to level off as the specialty lending businesses mature and the bank continues to reduce its branch count within its seven-state market area.

"Our revenue is significantly higher, but we have higher expenses," Dahl said. "Optimizing that expense base is really what the investor is looking for."

Some midsize banks have opted to merge with larger institutions rather than fundamentally change their business models in the face of declining fee revenue and stricter regulations. Chris Marinac, the director of research and managing principal at FIG Partners in Atlanta, cited Susquehanna Bancshares and National Penn Bancshares, both in Pennsylvania, as examples of banks above or near $10 billion of assets that opted to sell themselves rather than make the investments needed to expand. (BB&T acquired Susquehanna in 2015 and National Penn a year later.)

Marinac said it is only a matter of time before smaller regionals begin to pursue acquisitions more actively to try to gain the scale they will need to better compete with the larger banks.

"M&A is almost being forced upon these companies," he said. "They don't have to do it right away, but they really have to consider acquisitions to maximize their capital and their opportunities. It's tough to grow purely organically in that size range."

"M&A is almost being forced upon these companies," FIG Partners' Chris Marinac says of the regional banks. "It's tough to grow purely organically in that size range."

First Horizon Chairman and CEO Bryan Jordan agrees that more consolidation would be good for the industry, arguing that it would take out redundant costs in retail operations and financial reporting that, ideally, would translate into additional investments in technology and new products and services.

But Jordan said many regional banks like First Horizon are reluctant to do more than bite-sized deals because they are uneasy about crossing the $50 billion-asset threshold and suddenly being designated as "systemically important" and taking on even more compliance costs. (First Horizon's last whole-bank acquisition was in 2015, when it acquired the $430 million-asset TrustAtlantic Bank in Cary, N.C.)

That "bright line," Jordan said, "has been an inhibitor to what might be some attractive and logical consolidation. While you won't find many bankers who think 'too big to fail' is a good thing, you're not creating systemically important financial institutions at $50 billion or $70 billion in assets, you're creating more capability to serve customers and communities."

Jordan is the current chairman of the ABA's midsize banking group, and he has spent a lot of time in Washington lately urging policymakers to raise the SIFI threshold and lobbying for relief from what he calls "redundant" supervision. All banks with at least $10 billion of assets are subject to examinations from the CFPB, and many bankers contend that the threshold could be increased without weakening consumer protections.

"When it comes to consumer compliance, there is overlapping supervision between our regulators and the CFPB," Jordan said. "It's important to midsize banks to clarify the roles to eliminate that redundancy."

Jordan and other bankers believe that some new regulations put in place following the financial crisis have made the banking industry safer.

Webster's Smith cites stress testing as an example. "It may not need to be as expensive as it is — maybe it should be part of the safety-and-soundness exams — but if [regulators] were stress testing 10 years ago the way they are today, [the banking industry] might have avoided some pitfalls. I know a lot of our midsize peers agree with that," he said.

Even so, in this climate of heightened regulatory scrutiny, midtier banks have to rethink their business strategy to survive, Smith said.

"On a national scale, you're seeing a lot of companies investing in alternatives in which they can differentiate themselves, which is what we are doing with HSA and commercial banking," he said.

Select retail banking expansion is also part of Webster's growth plan, as evidenced by its decision to take over 17 former Citibank branches in Boston and neighboring suburbs in early 2016. The move nearly doubled its branch count in Massachusetts and increased its total branch locations in the Northeast to roughly 175.

Since the deal was just for the leases — it excluded loans and deposits — it allowed Webster to enter New England's largest retail banking market more cheaply than it might have had it bought a bank or pursued de novo expansion, Smith said. Though deposit and loan growth in those branches has been slightly slower than expected to date, Smith said he is confident that the bank will hit its target of $1 billion of deposits and $500 million of loans within five years given the size and strength of the Boston market.

"We're a little behind, partly because we stepped back from the pricing war, so we're a little indifferent as to where we are at the end of year one," Smith said. "We are looking at this as a five-year opportunity."

Webster is offsetting the cost of the Boston expansion somewhat by continuing to consolidate branches in other markets. The bank has closed roughly 20 branches in Connecticut since 2009 and planned to close eight more in Connecticut, New York and Rhode Island in the first quarter of this year. The median distance between closed branches and existing ones is 1.75 miles, Webster said.

Even adding in the new hires in Boston, Webster has reduced the head count at its branches by roughly 27% since 2009, said Nitin Mhatre, the bank's head of community banking.

Webster is also trying to keep marketing expenses in check in Boston by confining its advertising to digital channels, like the music streaming site Pandora, rather than buying up airtime on local television and radio. "The media costs in Boston are four times that of our core footprint, so we have to be selective," said Dawn Morris, Webster's chief marketing officer.

Still, it is in commercial and HSA banking where Webster is seeing the most opportunity for growth.

The shift to commercial banking began roughly a dozen years ago — when Webster switched to a commercial charter and John Ciulla, now Webster's president, joined the company from Bank of New York Mellon — and has accelerated in recent years as Webster moved more deeply into new markets and business lines.

Today commercial and commercial real estate loans account for nearly 60% of Webster's total loans, compared with roughly 47% in 2009 and 39% in 2004, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data.

Ciulla said its approach to expansion is to hire local bankers with a deep understanding of real estate values and the industries that drive local economies.

"We do not export people from our markets into new markets; we always find people that had been operating successfully in Boston or Providence or New York or Philadelphia," Ciulla said. "Most of them had embedded customers who were willing to follow them over to Webster. That's really how we have built the business."

HSAs, meanwhile, have been a key driver of that growth, providing Webster with a stable stream of low-cost deposits to support its commercial lending ambitions. It is no coincidence that Webster's funding costs have declined sharply in recent years — from 95 basis points in 2010 to 56 basis points in 2012 to 40 basis points last year — as HSA deposits have continued to increase. At Dec. 31, HSA deposits totaled $4.4 billion, up 144% from just two years earlier, according to Webster's annual report, filed in early March.

Last year the HSA business generated $71.7 million of fee income as well, up 151% from 2014, mainly from interchange fees on HSA cards and monthly maintenance fees that, for most account holders, are paid by employers. The business also brings in significant net interest income, which for HSA accounts represents the difference between the funding credit received reflecting the value of longer-duration deposits, minus the interest paid. All told, net income from HSAs more than doubled last year from two years earlier, to $38.2 million, even as expenses related to the business soared.

Fitzgibbon at Sandler O'Neill called Webster's HSA business "uniquely profitable" and said it has the potential to "grow at a rate that's much faster than traditional banking businesses and generate returns that are well in excess of what's feasible" for others in the industry.

Webster entered the HSA business in 2005 when it bought HSA Bank in Milwaukee, and for the first eight years, grew the business steadily, if unspectacularly, by targeting smaller employers and insurers. Today it counts two of the nation's five largest insurers as clients and controls 14% of the country's total HSA assets, according to the Devenir Group, an HSA consultancy.

It is now the second-largest HSA administrator in the country, behind only OptumBank, the HSA arm of United Health Care Group. Among traditional banks, its two closest competitors are Bank of America and UMB Financial in Kansas City, Mo., each of which has 5% market share, according to Devenir.

Fitzgibbon, who has been following Webster for more than 15 years, recalls that the bank invested in other nontraditional businesses over the years in an effort to boost profits — with mixed results at best.

Webster has owned a national mortgage warehouse lending unit, a wealth advisory firm, an insurance-premium finance company and an insurance subsidiary, but eventually sold them all because, as Smith said, "they were all smaller businesses that were sucking up management time and resources and were not earning their cost of capital."

With HSAs, though, Webster finally found a scalable, nontraditional business line that earned its cost of capital — and then some.

"I like to tell [Webster's executives] that they kissed a lot of frogs before they found their prince," Fitzgibbon said.