-

The midtier bank seemed destined for the endangered species list after the meltdown, but a fresh crop of small-bank survivors are eager to fill the void.

May 13 -

According to the standard antitrust scale, markets like Kansas City and Chicago rank as the most competitive, while markets like Charlotte and Buffalo are concentrated among a handful of dominant players.

May 9

Second of three parts

Large community banks that aspire to the next rung face a critical challenge: expanding in size and scope while maintaining their small-bank identity.

Banks on the cusp of midsize status — not quite regionals, but not quite community banks anymore either — must find ways to prove they will be good corporate citizens in their new markets, diversify products and evaluate top-tier management to meet the demands of a larger institution.

The real trick will come in making structural changes as invisible as possible to outsiders.

"There are two opposite things going on," said Mark Fitzgibbon, an analyst at Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP. "Underneath, you're trying to evolve and become a much more complicated company, but to the customer, you're trying to maintain that small, hometown, local feel. It's a delicate balance."

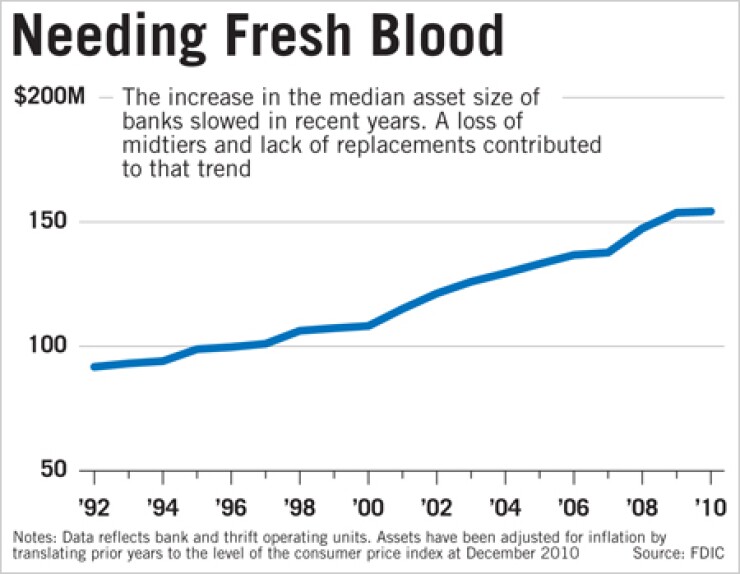

The industry has resembled a barbell in recent years, with the number of midtier, regional banks shrinking. Analysts and investors are looking to a new crop of banks to fill the gap, including First Niagara Financial Group and People's United Financial Inc. in the Northeast, IberiaBank Corp. and Hancock Holding Co. in the Southeast and Umpqua Holdings Corp. in the West.

As those companies expand into new territories via acquisitions, smaller banks are apt to portray them as big out-of-town banks. Community outreach, such as sponsoring local events, donating to charitable causes or financing community development projects, cannot be underestimated, said Jason O'Donnell, an analyst at Boenning & Scattergood Inc.

"What ends up happening in most cases is the financial impact of these philanthropic endeavors tends not to be significant, but the good will that's created in the community is huge," O'Donnell said.

Several analysts said Buffalo's First Niagara is an example of a company using outreach. Shortly after entering Philadelphia in 2009, the company pledged $650,000 to help close a funding gap and keep the city's public swimming pools open, and establish a program for free swimming lessons at 13 local YMCAs.

When First Niagara moved into Connecticut this spring, it agreed to be the lead sponsor of the New Haven Open at Yale, part of the Olympus U.S. Open Series, at a time when the tennis tournament's organizers said its future was in doubt.

John Koelmel, First Niagara's president and chief executive, said the company's goal is to establish itself as the leading corporate citizen in the new markets it enters.

"For us it's about building those relationships, leveraging what exists, or otherwise doing what we need to do to better solidify those relationships that will be important to our long-term success or better define how we can contribute to the long-term success and viability of the markets that we serve," Koelmel said.

Another way to break the big bank stigma is dividing a bank's footprint into smaller territories run by regional presidents, each of whom has a certain degree of autonomy, along with a mission to build customer relationships and act as the face of the local bank in each market.

"It's their market, and they're responsible for it," said Daryl Byrd, the president and chief executive of IberiaBank in Lafayette, La., which has 14 regional market presidents.

Each of Iberia's markets has its own advisory board made up of community leaders that meets twice a week, Byrd said. The goal is to help members network, while at the same keeping the bank in touch with its constituents.

At the Gulf South Bank Conference last week, for instance, Iberia hosted an event for the advisory boards to visit charter schools in New Orleans.

Advisory board members "were amazed at this different way to educate," Byrd said. "We got huge kudos, and that's an idea they can take back to their communities if they choose."

Such moves also benefit the company. "That tends to provide us with a networking structure," Byrd added.

There is a trade-off between localized decision-making and efficiency, O'Donnell cautioned.

"Having a large leadership team in each core market — that's going to create potentially some efficiency problems," O'Donnell said. "Conversely, if you have no leadership in those markets, then you can make some poor decisions and that can come back to bite you later."

Finding and keeping the right people in new markets is critical, analysts said. Banks must work hard to connect with customers, especially after acquisitions, lest they feel ignored or unloved by their growing bank.

"You have to make sure that you've locked up the best commercial lenders and that you have managers in the markets that you've acquired that are known commodities to both commercial and retail customers in those communities," said Matthew Kelley, an analyst at Sterne, Agee & Leach Inc.

In some cases, limiting the pace of change after an acquisition can help mitigate customer shock, O'Donnell said. For instance, Hancock, in Gulfport, Miss., which is set to buy Whitney Holding Corp. in New Orleans, has said it plans to keep the Whitney name on branches in Texas, where Hancock has no presence, and Louisiana, where the Whitney brand is stronger.

Midsize companies also need to continually reevaluate upper level talent, Fitzgibbon said.

"I think as you become a regional bank, you really need to demonstrate to the market that you've brought in people with experience in a variety of different kinds of institutions and with a broad enough background that they can help you run this much larger company," Fitzgibbon said.

First Niagara hired David Ring, a former executive at Wells Fargo & Co., as its New England regional president this year. It also hired a new chief financial officer, Gregory Norwood, a former president and chief risk officer for Ally Bank in Detroit.

The $23.8 billion-asset People's United in Bridgeport, Conn., made a similar move in February, when it hired Kirk Walters, a former senior executive vice president and director of Santander Holdings USA Inc., the parent of Sovereign Bank, as its chief financial officer.

Ray Davis, the president and chief executive of Umpqua in Portland, Ore., said keeping employees happy keeps customers happy, too. That started with building a culture at Umpqua that empowers people to make decisions on their own, he said.

Over the last 15 years, Umpqua expanded from a six-branch bank to 185 offices across the Pacific Northwest. In the process, Davis said, Umpqua developed its own formula-based system for measuring service, called return on quality.

"This has enabled our people to compete in our markets with more than price, and that is huge," Davis said.

In addition, Umpqua's employees have helped the company make Fortune magazine's "100 Best Companies to Work For" for the past five years.

"I think most of the time most companies — it's not just banks — most companies that just grow for the sake of growth, basically they forsake their culture too many times," Davis said.

"The challenge for us … is we have to be able to look back and say at $30 billion [of assets that] we're stronger than we were at $12 billion," he added.

Editor's Note: This is the second in a series about the plight of today's midtier banks and the prospects for future ones. What's next: Some midtiers are fiercely fighting to stay independent.