-

Are you pushing back when you think examiners go too far? How's that working? One Ohio banker tried it, and instead of retribution he got relief.

August 17 -

Jeff Gerrish, a lawyer in Memphis who spends a lot of his time advocating on behalf of community banks to federal regulators, sees a thawing in banker-regulator relations, but says it is one born of fatigue rather than enlightenment.

August 17

Retribution.

Say the word to anyone in banking and they immediately get the context: bankers fearing a backlash if they complain about examiners.

It's been the industry's Achilles' heel for years. Policies are misapplied or misinterpreted and no one does anything about it because there is no objective feedback mechanism.

Until now.

A group of state associations, led by Utah, working with the American Bankers Association, has developed an electronic, anonymous survey bankers complete after each exam. It asks dozens of multiple-choice questions designed to assess how satisfied the banker was with the exam and the examiner. A series of narrative questions give bankers space to explain their experience, including what issues examiners focused on most.

"This was born out of years of frustration," said Wayne Abernathy, the ABA's executive vice president for financial institutions policy and regulatory affairs. "When we took complaints to the regulators, we got one of three responses: 'No, it didn't really happen, or he's an outlier, or let us know who he is, we want to talk to him.' Well, that's the last thing the banker wants. He's afraid regulators are going to jump all over him.

"We wanted to get away from the anecdote and find the real trends. So now when we go to the regulators we can say this isn't an anecdote anymore. It's happened 50 times."

During the effort's first six months, bankers in 36 states have completed 1,037 surveys. Not enough to draw hard conclusions or indicate trends over time, but enough to have an impact.

"Now that regulators know we have this window into their world, things like professionalism and courtesy and respect have improved," says Howard Headlee, the president of the Utah Bankers Association. "They know that we have this feedback loop now, and we are going to know if examiners aren't treating bankers" well.

Headlee has been working on what's now known as the "regulatory feedback initiative" since 2005, but only gained real traction in late 2010 when Abernathy signed on. They have recruited dozens of states and are working on signing up the rest.

Headlee says the survey results can help bankers prepare for exams; aggregate data can be broken down to show what's happening at banks of a certain size, those overseen by a particular regulator or in a certain part of the country.

"I generate some basic reports that I distribute to all of our banks and then I do custom reports for banks who request them," Headlee says. "I can break it down so a bank can see how similarly situated banks are being treated, and what they are being scrutinized on. And hopefully that helps them avoid surprises. My banks want to comply. What they are tired of is being ambushed."

Abernathy says the survey results should help influence public policy. "We're trying to restore the exam experience to what it should be: a valued-added experience."

Asked if she thinks the survey results could affect exams, Jennifer C. Kelly, the OCC's senior deputy comptroller for midsize and community banks, says, "Absolutely."

"If something shows up that seems to be a trend, it will definitely provoke some conversation" at the agency, she says. "If it's in a particular part of the country or a particular topic, I would certainly talk to the management team in that area or talk to my entire management team about what's going on with a particular issue."

As they developed the survey, Headlee and Abernathy met with officials from all the federal agencies in early 2011 and again that spring. "We showed them the questions before we went live," Headlee says. The agencies, particularly the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., were supportive, he says.

The survey starts with simple demographic information — no names. Just charter type, asset size and which agency conducted the exam.

It asks how long the exam lasted and whether the bank's Camels rating improved, declined or stayed the same. Bankers are asked to rate on a scale of 1 to 5 how satisfied they were with the exam, how knowledgeable the examiner was with both the institution and the regulations and how willing he was to discuss issues with the bank's staff.

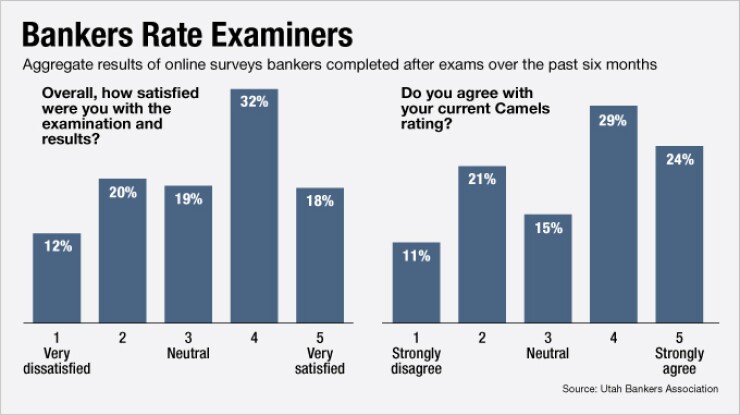

Then the survey drills down into elements of the exam: classified asset levels, loan concentrations, underwriting, reserves, capital, liquidity, funding, risk management, among many others. (That's for safety and soundness exams. There is a separate survey to cover compliance exams, but just 251 of those have been completed so far.) Surprisingly, given the level of angst over exams these days, half of the bankers said they were either satisfied (32%) or very satisfied (18%) with their exam and its results. Slightly more, 53%, said they agreed with their Camels rating.

However, 32% of bankers said they were dissatisfied with their exam, including 12% who said they were very dissatisfied. One-third of bankers said they did not agree with their Camels rating. "We want that improved and so do the folks in Washington," Headlee says.

Nearly one in three bankers (29%) said their bank is under a written enforcement order with their regulator.

But a turning point seems to have been reached on safety and soundness exams: 20% of the bankers said their Camels rating improved while 17% said it declined. The opposite is happening with compliance exams: 8% of bankers said their rating improved while 22% said it declined.

"We can see that from a safety and soundness standpoint, the pendulum is coming back," Headlee says. "On compliance, the pendulum is still swinging out."

One fun statistic: the 1,037 safety and soundness exams took a total of 17,086 days. The longest exam took 300 days, but the median was a way more normal 13 days.

Bankers also had plenty of good things to say about their examiners: 66% said the exam staff was knowledgeable about the bank; 68% said the examiners were well versed on the rules; and 59% said their examiner was "flexible and open to the exchange of view with my staff."

Replies to five questions about how the examiners acted were also largely favorable: 72% of bankers said their examiner was professional; 60% described their examiner as helpful; 59% said he was fair; 52% said he was objective and 46% said he was pragmatic.

The key issues examiners will be emphasizing over the next 12 to 18 months include interest rate risk, unfair and deceptive practices, succession planning and compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act, according to the survey results.

Not surprisingly, the two biggest stumbling blocks for bankers are credit-related. How assets are valued and credit administration were the two problems cited most often by bankers who completed the surveys.

Of course these are aggregate numbers (as of Jan. 13) for the entire country and covering every agency.

Drill down in the data and some problems emerge. For example, a bank overseen by the FDIC is more than three times as likely to be criticized for violations of fair-lending laws than a bank regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency; 80% of the banks regulated by the FDIC's Chicago office have been criticized for fair-lending violations.

Abernathy said industry representatives will keep an eye out for these types of anomalies and bring them to regulators' attention.

Headlee hired a customer-feedback firm in Salt Lake City, Allegiance, to build and run the survey. Its reputation for protecting participant identities was a strong selling point for Headlee.

"I had to be able to assure every banker there is no way, not even if the regulators subpoenaed the data, there is no way to tie this back to your bank," he says. "I have to be able to appease the most paranoid banker out there that there is no way this could be tracked back to their institution."

The survey itself is closely guarded. Only a bank's CEO may request a copy from his state association. The association chief will verify the request and allow the CEO access to the survey. To protect outliers, if a particular query yields less than five results, then the program won't provide any data.

"You're now able to quantify the complaints you get on a particular topic," said Don Childears, the president of the Colorado Bankers Association. "And that is really meaningful because before, when you would relay an anecdote, you didn't know if you were overstating a case or not. By quantifying all this I think you get a more realistic representation."

Mike Van Buskirk, the president of the Ohio Bankers League, added: "It keeps both sides honest."

Ten or so states are missing from this effort, including some influential ones like California and New York. Illinois, North Carolina, Georgia, Maryland, Alabama and Iowa have taken a pass as well.

Only the California Bankers refused a request for an interview. The most common reason given by the other state associations was that they already have means for sharing feedback with state and federal regulators.

"Our feeling was what we're doing today is working. We didn't think we needed it," said Mike Smith, the president and CEO of the New York Bankers Association. "If there is a problem, we know about it and deal with it."

Kathleen Murphy, the president and CEO of the Maryland Bankers Association, said her members had several concerns, including whether participation would upset examiners and whether the results would be skewed because most respondents would be bankers in some sort of regulatory difficulty.

"We take a really deliberative approach to things like this," Murphy says. "Our board said let's take a wait and see approach."

Linda Koch, the president and CEO of the Illinois Bankers Association, says her group started a similar effort about six months earlier and she didn't want to ask members to fill out a second survey. Still, Koch called the national effort "outstanding" and said Illinois may reconsider and join.

Abernathy and Headlee would love to get every state on board. Abernathy insists the survey is not about "putting the regulators on the spot."

"It is really an effort to get out of where we both hated to be, which was stuck with the anecdotes, and get into what's really going on."

And with all the Dodd-Frank rules coming down the pike, Headlee predicts the need for such a feedback mechanism will only grow.

"Even if everybody was well intentioned, this many new regulations are going to be applied in the field disparately," he says. "There is just no way that these various agencies are going to impose this number of regulations completely uniformly."

Barb Rehm is American Banker's editor at large. She welcomes feedback to her column at