-

There's bad news for those who withdrew funds on Bank Transfer Day to punish the targets of their ire. Most banks don't really need their money at least not right now.

November 9 -

Higher account maintenance fees are inevitable, because basic, relatively low-balance checking accounts are simply not profitable on their own.

November 1 -

The attempt by large banks to impose debit card fees wasn't just about wringing a bit of extra revenue out of existing customers. It was an effort by Bank of America and its competitors to rework their basic retail account business model.

October 31

For banks, free checking is many things — but it isn't free.

Despite a

The average checking account cost banks $349 in 2011, says Mike Moebs of Moebs Services Inc, a research firm. But the average revenue per account is just $268, implying a loss of $81.

That equation helps explain the thinking behind some of the recent,

"Banking is a subsidized business," says Hank Israel, a partner at New York-based consulting firm Novantas LLC, pointing to the fact that the profitable accounts balance out those accounts maintained at a loss. "When the plane flies full, coach covers the whole cost and first class is the profit," Israel says.

But thanks to new regulations, including the Durbin amendment in the Dodd-Frank Act, which caps fees on debit interchange, the number of profitable customers is falling. Those fee caps, which went into effect on Oct. 1, are expected to eliminate more than $5 billion in annual bank revenues.

"Since Durbin, the coach class isn't breaking even, so the profit [on checking accounts] is being cross-subsidized by [deposit] balances, and with interest rates so low that's not covering costs either," Israel says.

He estimates that one third to one half of checking account customers are now unprofitable for banks.

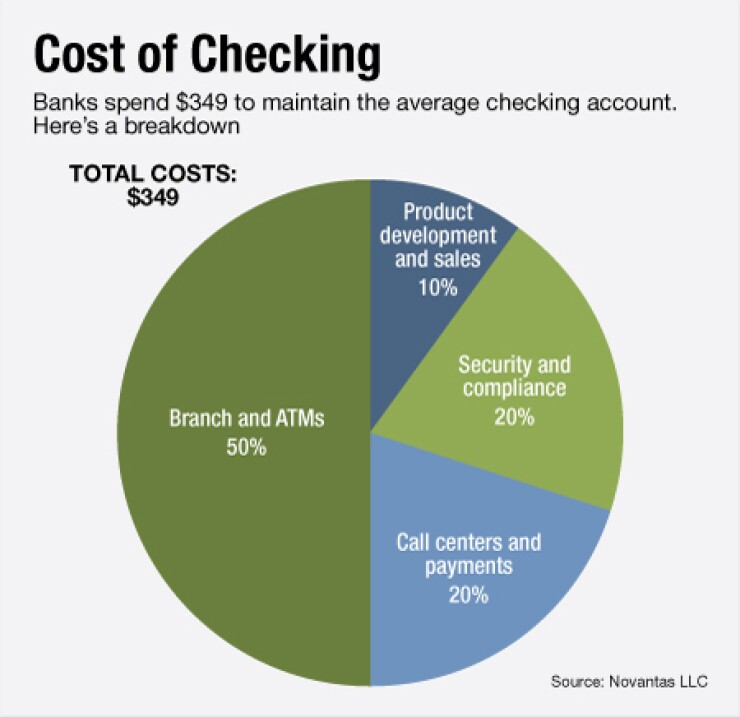

The single biggest cost, Israel says, is the cost of bank branches and ATMs. Another 20% is spent on back-office functions, including maintaining call centers and payment operations.

Overhead costs, including executive salaries along with security and compliance expenses, also account for about 20% of the costs. The last 10% covers product development and sales.

The mismatch between the costs and the returns of checking accounts is untenable for the industry at large. But as banks consider what the new regulatory landscape means for their account offerings, analysts caution that the solution is not likely to be one-size-fits-all.

This is in part because the costs to maintain

For the largest banks with assets greater than $50 billion, the average checking account costs between $350 and $450 a year, according to Moebs. Overhead, or the institutional costs not associated with a specific division or service, is what weighs down some of the largest banks, making it more difficult to cut costs, he says.

But he adds that for some of the smaller banks with less than $5 billion in assets, the costs are much lower — around $175 to $250 a year.

The sweet spot for breaking even or squeezing out a profit on free checking is likely to be among the mid-sized institutions.

The issue comes down to efficiency and economies of scale. The banks likely to fare best are those that are big enough to support a sizeable base of checking account customers, but which are not loaded down with ancillary costs.

"The community banks and the credit unions will offer free checking and will get revenue — the major item is from overdrafts — and that revenue and other revenue, such as transaction revenue, it's enough for them to break even," says Moebs.

For those institutions, offering free checking brings more customers in the door — giving the banks an opportunity to turn a profit eventually.

"They've got a free name and address and telephone number and hopefully an email address," he adds. "What that they can do is cross-sell and get more business. That's the true purpose free checking."

Such a strategy is not likely to be sustainable for megabanks like Citigroup Inc. and Bank of America Corp. Those are the companies that reacted to the Durbin amendment by

"The big guys are operating checking at a loss," says Moebs. "The big guys have to get out of this business because with [cuts to] interchange and overhead revenue, they don't have enough to cover their costs."

But Israel of Novantas cautions that free checking may not be a winning solution for all smaller institutions. He notes that those customers who are likely

"Based on the work that we've done, the accounts in motion tend to be lower in deposit levels and less complex relationships," in part because those accounts are the easiest to move from one financial institution to another, says Israel.

In addition, "with so many offers on the market as larger banks try to improve account quality, only the accounts impacted by [checking account] fees are moving banks," he says.

Those checking account fees are designed to recoup the costs of serving customers who keep small deposits with the bank, complete few transactions each month, or have not bought other, higher-margin bank services like mortgage loans.

If small banks offer free checking without considering these factors, there could be a "deluge of customers seeking free checking whether or not [the bank has] capacity to service them along with their more profitable customers," Israel says. "They can definitely move volume, but are they moving value?"

Nevertheless, some "small challenger banks… are really in a position to acquire these customers. They have lower cost structures because they either organize themselves online or have very concentrated focuses," says Israel.

The migration to online and mobile banking could be the great equalizer for institutions of various sizes, as more customers look to the internet and smart phones to do their banking.

A 2010 study by consulting firm Javelin Strategy & Research found that the average cost per bank transaction varied hugely depending on how the customer made the transaction.

Javelin estimated that an in-person transaction at a physical branch cost a bank $4.25, while a phone call to a call center or the use of an ATM cost $1.29 or $1.25, respectively.

By comparison, mobile banking transactions cost just 10 cents, and online banking transactions cost just 19 cents.

Overall, Javelin found that customers not using online banking cost banks $359 a year. That was $167 more than the annual cost of $192 for customers using online banking services.

If banks can reduce the number of customer service calls associated with online banking, the cost differences could be even greater, says Mark Schwanhausser, a senior analyst with Javelin.

"If we can move customer service representative calls back to self-service online banking, something that became an added cost [with online banking] becomes an added efficiency," Schwanhausser says.