-

Joseph Smith, who is responsible for monitoring the 49-state mortgage servicing settlement, plans to spread the work among multiple consulting firms.

June 5 -

Industry watchers expecting foreclosure trends to follow a predictable path are destined for surprises, as the recent figures from RealtyTrac demonstrate. March marked a 4-year low in new foreclosures, with actions increasing in judicial states, but surprisingly declining in non-judicial ones. In the aftermath of the AG settlement with the major servicers, this result seems counterintuitive to say the least. However looks may be deceiving on closer examination.

April 16 -

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau outlined a slew of new rules it plans to propose this summer that the industry said could require expensive systems upgrades for servicers.

April 10

Among the strongest industry rationales for a national mortgage servicing settlement was that it would break the legal stalemate over a huge backlog of delinquent loans. Banks would give principal writedowns to eligible borrowers and confidently foreclose on the rest, allowing the housing market to move on.

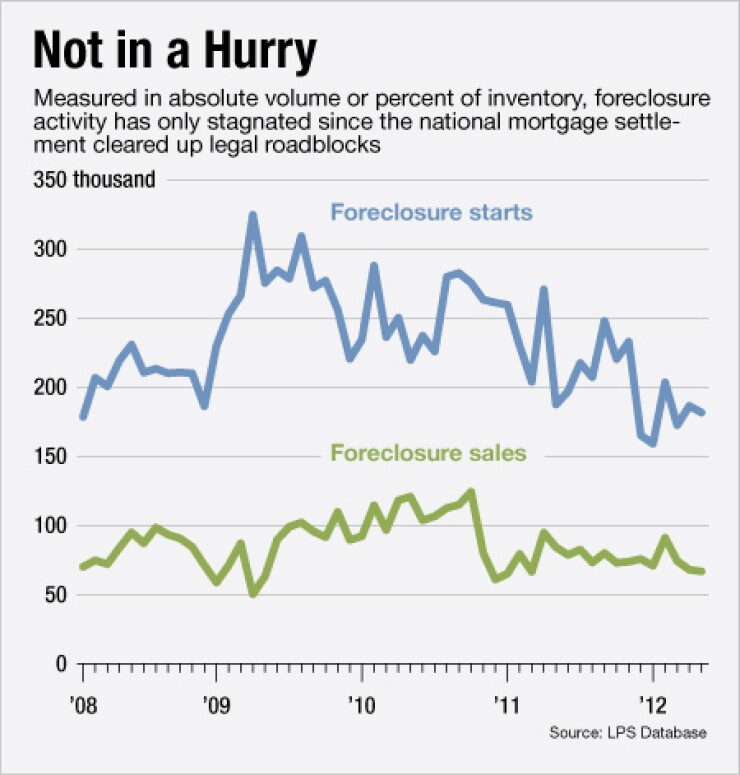

Five months after the deal was formally struck, the promised spike in foreclosures hasn't arrived. For most of that time, activity slipped even further. The promised flow of foreclosures and other loan resolutions may still be on its way, but there's little evidence of an abrupt upswing.

Paradoxically, the continued slowdown may be the result of the settlement itself, industry members say. The deal, agreed to by the five banks that control 70% of the servicing market, removed much of the legal risk stemming from foreclosures. But that obstacle has been replaced by new foreclosure delays. Banks have to adapt to changing servicing standards, and they are also trying to qualify as many borrowers as possible for credits, in order to reduce their actual cash liabilities from the settlement. "The word that's missing is yet. There's a bottleneck of foreclosures which still has to get worked" through, says Michael Feder, the chief executive of Radar Logic, who predicts that the oversupply of homes relative to demand will persist for years.

Some observers see an incipient thaw in foreclosures that suggests the gridlock may be almost over. RealtyTrac, which predicted in April that "the dam will burst" and a flood of foreclosures and short sales would soon be unleashed on the market, reported that new foreclosure filings in May rose for the first time in 27 months. The volume of overall foreclosure filings in judicial states — where banks faced the most robo-signing concerns — rose 26% in May from a year earlier. (But at the same time, overall filings in nonjudicial states dropped by almost the same rate.)

CoreLogic, another mortgage data provider, has trumpeted a two and a half year

But while such data suggests a change may be on the way, it has yet to show a significant change in core foreclosure volumes. Foreclosure activity is still down year over year, and foreclosure starts in portfolio, privately securitized loans and loans backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were all around post-crisis lows in April, according to the most recent Lender Processing Services review. (An apparent rise in Federal Housing Administration foreclosures bridged the gap, though the FHA has raised questions about that data's accuracy.)

One regional data provider looking at foreclosures on the ground sees no sign that servicers are planning to accelerate their processing of defaults. ForeclosureRadar, which monitors courthouse foreclosure activity in California, Nevada and Arizona,

Industry sources say that the settlement itself has necessitated a broad review of their delinquent portfolios. The national mortgage settlement

Banks "have to recover billions through credits," says one executive at a large servicer. "They want to make sure they don't put anyone into the foreclosure process if they qualify for a credit."

Moreover, it takes additional staff to process loans through foreclosure. Since most of the large servicers are still in the process of training people in the new servicing requirements of the settlement, many of the delayed foreclosures have simply not been processed yet.

Diane Cassidy, who works in the law offices of James Kajtoch, and helps borrowers obtain loan modifications says more borrowers are qualifying for modifications and principal writedowns because of the settlement. One borrower who had been declined eight times was just approved for principal reduction of $375,000 on a $560,000 loan. "No one will come out and tell the borrowers that they qualify for the DOJ settlement but it has helped [homeowners] a lot," Cassidy says.

If settlement-driven resolutions pick up pace, that would also limit foreclosure activity. Cassidy says there's still plenty of room for improvement.

"The consumers are still baffled about submitting paperwork and the communication level with the banks is still horrid," she says.

The current level of foreclosures isn't high enough to quickly clear the market of the 1.6 million home loans that LPS says are more than 90 days past due and the 2 million additional loans somewhere in the process of foreclosure.

Foreclosures and distressed sales aren't the only pressures on the market, either:

Banks with hundreds of thousands of real estate owned properties are in no hurry to dispose of them because doing so would drive prices down even further, housing experts and economists say. "While the banks clearly want to dispose of this inventory to free up capital, they don't want to severely damage the assets coming in," Feder says. "Those that are calling this a housing recovery are very premature because there's just too much inventory, not all of it is for sale, and you don't see it."