ST. LOUIS — Many community banks are at risk of becoming irrelevant unless they rethink their business models.

That was perhaps the key takeaway at a community banking research conference hosted by the Federal Reserve and the Conference of State Bank Supervisors this week, where bankers, regulators and other industry experts painted a stark picture of what the new normal will be for smaller institutions.

Persistently low loan yields, increasing competition from credit unions and fintech firms and little relief from regulation pose the most serious challenges for community banks. Banks in slow-growth markets will be particularly hard-pressed to find the new sources of revenue they will likely need to remain competitive, said Julie Stackhouse, managing officer of banking supervision, credit, community development and learning innovation at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

“I can’t help but be just a little bit anxious about some of the challenges we could see in the next few years,” she said in an interview after the conference ended. “The community banking system is the healthiest it has been in eight years but … we know there are some headwinds. There’s the cost of regulation and we know some communities are really struggling due to out migration, making it increasingly difficult for banks to diversify their balance sheets.”

John Williams, the CEO of the San Francisco Fed, gave banks a hard dose of reality when he said that “like the pager, the Walkman and hopefully the Macarena," the high interest rates banks enjoyed in the 1990s are never coming back. Low rates also make it more challenging for the Fed to stimulate the economy, Williams added.

“Bottom line: In the new world of moderate economic growth, banks need to plan for lower rates," Williams said. "Banks, and everyone else, need to prepare accordingly."

For some, expansion into new markets and business lines could be the keys to survival. For others, though, survival may be about not trying to be all things to all people.

“Focus on your market,” Brian Graham, the CEO of Alliance Partners, said during a panel discussion. “Use the power of your charter to focus on something that you’re good at.”

The future will be “bleak for many and brilliantly shiny for some,” added Steve Streit, the president and CEO of Green Dot. “The bright community bank of the future may not have a branch or office. It might only be online or specialize in something like soybeans or companies that make auto rims. … You have to be obsessed with being relevant.”

Despite successful efforts to exempt banks with less than $10 billion of assets from some of the most onerous post-financial crisis rules and regulation, regulatory burden remains a big concern for banks in that asset group.

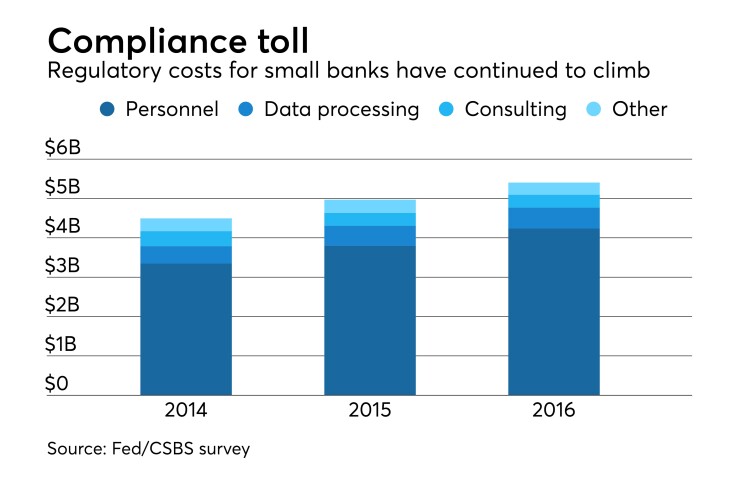

A Fed/CSBS report released at the conference estimated that regulatory expenses rose by 8% in 2016 from a year earlier, totaling $5.4 billion, or an amount equal to nearly 25% of community bank net income. Such costs jumped by 20% between 2014 and 2016.

While the vitriol has subsided some in recent years, a number of bankers made it clear in the survey that they are tired of absorbing compliance costs. The survey, which polled nearly 600 bankers, kept individual comments anonymous.

Regulations “have come at such a pace that we are drowning … in what most of us believe is nonsense,” one banker lamented as part of an open-ended question in the survey. Another respondent predicted that “the community bank is dead with regulatory interference.”

“NASA can land a rover on Mars with a higher degree of error than I’m allowed in my HELOC portfolio,” another vented.

Bankers pointed to specific regulations that restrict dealings in areas such as mortgages, small-business lending and unsecured small-dollar loans. They also factor into M&A decisions.

Most of the costs involved personnel, with data processing and consulting also playing a role.

“Anytime they adopt of these [regulatory] programs it becomes one more thing that requires an internal audit,” said Michael Stevens, a senior vice president at the Conference of State Bank Supervisors.

While three-fourths of survey participants offer home equity lines and plan to continue doing so, such credits made up just 4% of total loans at small banks. More than half of the bankers that plan on exiting the business cited too much regulation as the reason for their decision.

Highly touted programs such as Small Business Administration lending remain daunting for most community bankers. While 38% of the survey’s respondents define all of their commercial credits as small-business loans, only 15% said they frequently originate SBA loans.

“We do very little” SBA lending, Harold Miles, CEO of the $321 million-asset Bank of Advance in Missouri, said in an interview. “It is cumbersome and we don’t have people who are geared to doing it all the time. When that’s the case you can’t get the scale, and when you can’t get the scale you can’t justify doing many of those deals.”

Miles was also among the bankers who expressed concern over the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s proposed data-collection rule for small-business loans.

The threat of increased competition weighs heavily on the minds of bankers. While many of community banks still view each other as competitors, 10% of respondents flagged credit unions, which are getting more encouragement to make SBA loans, as a source of future competition. Another 7% pointed to fintech firms.

“People are worried more about the credit unions as they gain the ability to do more small-business lending,” Peter Schork, CEO of the $289 million-asset Ann Arbor State Bank in Michigan, said in an interview.

Increased regulatory burden has also spurred more bankers to mull consolidation. Roughly half of the bankers surveyed said that regulatory costs played a “very important” role as they considered buyout offers. The industry has lost nearly 1,500 banks over the last five years due primarily to consolidation.

More than 11% of the bankers surveyed had “received and seriously considered” an offer from a potential acquirer in the last year. Almost 20% had attempted to buy another bank.

Still, bankers must maintain some perspective as consolidation occurs, David Hanrahan, the CEO of the $465 million-asset Capital Bank of New Jersey in Vineland, said during a panel discussion on the future of community banking.

"While it isn’t good public policy to have fewer community banks, who doesn’t like having less competition?"