It has been an article of faith in the industry that banks need to have holding companies if they want to raise capital, add new business lines or move into new markets.

But now, more than 60 years after President Eisenhower signed the Bank Holding Company Act into law, benefits of the business model no longer appear as clear-cut. It has been two decades since banks have needed holding companies to branch across state lines and new rules enacted after the financial crisis have, to some degree, eliminated capital-raising advantages held by banks with holding companies.

Experts are quick to note that some of the industry’s most highly regarded institutions — First Republic Bank in San Francisco Signature Bank in New York — have grown quickly and raised capital without such a structure. In the past year, three other regionals — most recently Zions Bancorp. in Salt Lake City — have moved forward with plans to ditch their holding companies, citing a desire to trim compliance costs.

With questions swirling about the usefulness of holding companies, banks across the country are beginning to ask: What’s the modern business case for having one?

“Holding companies are not what I would call the natural state of banking,” said Rodgin Cohen, senior chairman at Sullivan & Cromwell, who recently spoke on the topic at a conference attended by 75 bank executives and sponsored by Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

The Federal Reserve oversees holding companies, while a bank’s primary regulator oversees the subsidiary, so by dissolving their parent companies, banks can eliminate a duplicative layer of oversight, Cohen said. They can also eliminate what he described as a “Noah’s ark approach” to compliance, or the need to have two sets of directors and regulatory examinations, for both the subsidiary bank and the holding company.

There are, of course, strategic advantages to having a holding company. Holding companies provide the industry’s smallest banks with the ability to incur significantly more debt than larger peers, while also providing big banks the ability to diversify beyond simply making loans and taking deposits.

Moreover, once a holding company is eliminated, banks no longer register with the Securities and Exchange Commission, and that can be problematic for publicly traded banks in certain states. For example, most states require banks to have holding companies if they want to redeem their own stock.

But for midtier banks that have relatively straightforward business models, a case could be made for ditching their holding companies, experts say.

“There’s not a right answer [for the industry as a whole], but there is a right answer for every individual bank,” Cohen said.

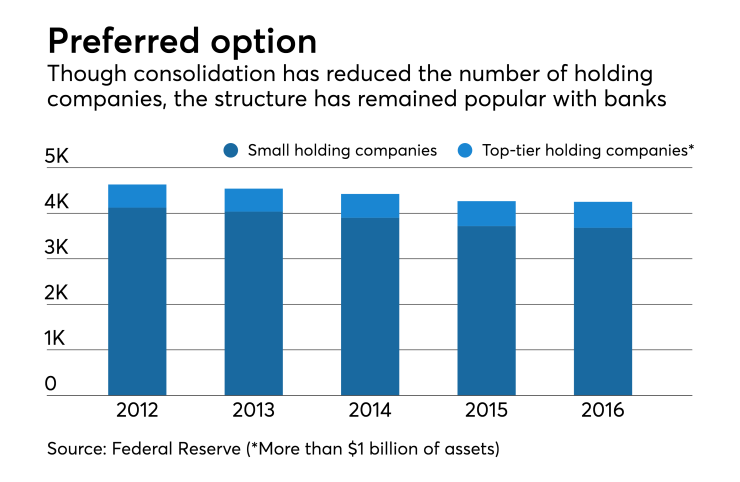

It’s striking that the question is being asked in the first place, given the near-ubiquity of holding companies in banking.

There are currently 4,615 holding companies in the industry, the vast majority of which operate as the top parent in their corporate structures, according to the Fed. That means most of the nation’s 5,700 banks are affiliated with a holding company.

Questions about their usefulness have emerged amid a broader deregulatory push in Washington. Among the most vocal detractors has been former acting Comptroller of the Currency Keith Noreika,

“Nothing in law requires their existence, and they serve no inherent banking purpose,” Noreika said, noting that holding companies are unusual in the rest of the world.

Noreika, said that interstate banking and other legal developments related to the mixing of banking and commerce have largely eliminated the need for holding companies. He also argued that holding companies — which are designed to act as a source of strength for their subsidiaries — do not necessarily reduce risk in the financial system.

“For these reasons, bank holding companies may have outlived their practical business value and may, in fact, be obsolete,” Noreika said.

Whether or not it makes financial sense for a bank to get rid of its holding company largely depends on its size, according to banking attorneys.

For community banks with under $1 billion in assets, having a holding company can be a major financial advantage, given the benefits that are provided to under the Fed’s Small Bank Holding Company Policy Statement.

Among other advantages, small bank holding companies are allowed to incur debt at the holding company level and inject it as capital in their subsidiary bank. Small companies can also use debt to finance up to 75% of the purchase price of an acquisition.

“It was designed to preserve community banks, to enable them to be sold and to buy back their stock,” Chip MacDonald, an attorney with Jones Day, said of the policy, which dates to 1980.

On the other end of the asset-size spectrum, larger, more complex banks often use holding companies to expand into other lines of business, such as insurance or equity securities underwriting. Additionally, the structure gives companies the ability to make equity investments of up to 5% in other firms without regulatory approval — a particularly important took for banks with an interest in fintech.

“The business case is, really, to engage in a broader range of activities,” Cohen said.

But for banks with asset sizes in the middle — the regional banks that mostly stick to making loans and taking deposits — the benefits are harder to spot.

Over the past several months, three regionals — Zions,

For the $65 billion-asset Zions, in particular,

“The major benefit is really a little greater flexibility, and not having to worry” about the Fed’s annual Comprehensive Capital Analysis and review, Simmons said during a Dec. 5 conference sponsored by Goldman Sachs.

After a decade marked by escalating compliance costs, the handful of regional banks that are going it alone without a holding company are showing the industry how to navigate stringent regulatory requirements at a lower cost, said Tom Michaud, KBW's chief executive.

“Dropping a regulator isn’t an argument for less regulation — it’s an argument for more efficient regulation,” Michaud said.

For its part, the Fed has not taken an official position on the matter.

Obviously, the central bank would have less direct oversight of the industry if more banks did away with their holding companies. But Cohen said that the Fed’s primary concern is keeping tabs on the biggest, most systemically important banks. JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America together control over 20% of the industry’s deposits.

“I don’t think the Fed would [worry about losing oversight] unless some of the very big banks started doing it — and the very big banks really can’t do it,” Cohen said.

Another question is whether eliminating a holding company provides significant savings to a bank over time. So far banks have offered mixed messages on the matter.

Though Zions would no longer be subject to certain stress tests, Simmons said he would expect expenses to decline only “around the margins.” But Bank of the Ozarks CEO George Gleason described his company’s move as a “pure efficiency play” during an April conference call announcing his decision, though he did not provide details.

While ditching a holding company

“There is still value in the structure because of that leverage, and because of that liquidity,” said Scott Coleman, an attorney with Lindquist & Vennum in Minneapolis.