-

The Treasury Department announced the last group of banks that will receive capital under the Small Business Lending Fund, which distributed more than $4 billion to 332 banks, falling far short of industry expectations.

September 28

WASHINGTON — When the Troubled Asset Relief Program got off the ground at the height of the financial crisis, small banks were an afterthought.

At the last minute, Congress even had to insert language into the law to ensure that financial institutions of all sizes would have access to the program.

Now, in an ironic twist as Tarp approaches its third birthday next week, small banks are virtually the only institutions left in the bailout program.

Out of roughly 400 financial institutions that still have Tarp funds, only a handful have more than $1 billion, including the insurance giant American International Group. The vast majority of today's Tarp recipients hold less than $100 million.

Many community banks are struggling to repay the money. The reason is hardly a secret.

"The long answer, the middle answer, and the short answer is they don't have sufficient capital," says Neil Barofsky, the former inspector general of Tarp.

The government's most appealing escape hatch closed this week, when the Small Business Lending Fund stopped providing funding to banks.

The SBLF generally offered a cheaper alternative to Tarp, but the banks that were able to take advantage are in the minority.

Out of at least 319 Tarp recipients that applied for SBLF funds, only 137 eventually received the money.

In addition to the banks whose applications were denied, other Tarp banks were discouraged from applying because the SBLF's rules made clear that they would not qualify.

As a result, the prospects for many small banks in Tarp, which already looked bleak when the SBLF began a year ago, seem even darker today.

At least 170 of them have missed two or more of the quarterly dividend payments they owe to the Treasury Department. Such payments are set to jump to 9% from their current rate of 5% in two more years.

There are several reasons so many small banks have had a hard time leaving Tarp. For one, small banks, many of which are privately held, simply lack the access to capital markets that large banks enjoy.

"That's why, of course, we've been able to see that a lot of the larger banks have repaid Tarp funds," Assistant Treasury Secretary Timothy Massad told Congress in March. "Many of the smaller banks have not, because it's more difficult for them to raise money to do so. But we're continuing to work with them."

Barofsky said in an interview that in the beginning, the program offered a way to recapitalize some of the largest U.S. banks with taxpayer dollars.

In late 2008 the Treasury was so eager to get cash out to the largest banks that it didn't even require them to apply for the funds. That changed once small banks wanted to apply for money.

The Obama administration pushed large banks to leave the program, Barofsky says, noting that the government opted to convert its preferred investment in Citigroup Inc. into common stock.

"As much as they were motivated to get them in at the height of the crisis, they were equally motivated to get them out," Barofsky says.

Community banks, however, were largely left to struggle on their own, with the exception of the creation of the SBLF. The program was nominally pitched as a way to increase small-business lending, but it also allowed financial institutions to convert Tarp funds. Doing so allowed small banks to escape both the stigma of Tarp money and its restrictions, while providing added benefits.

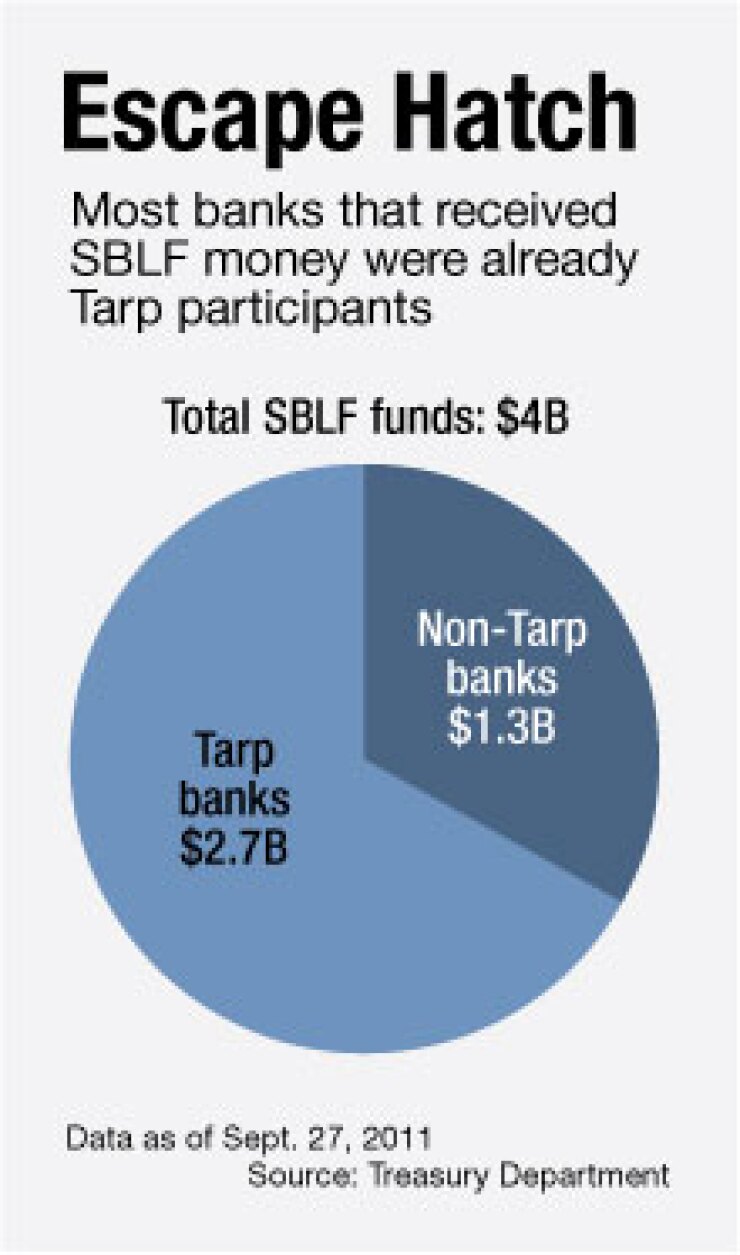

By this week, when the final SBLF disbursements were announced, about two-thirds of the $4 billion awarded had gone to Tarp recipients, allowing those institutions to refinance one form of government capital with another, more attractive form.

Under the SBLF's terms, small banks initially pay 5% dividends, but that figure can fall as low as 1% based on increases in small-business lending. The SBLF also pushes back the date when banks will have to start paying a higher dividend rate if they don't repay the money.

"So SBLF looks in part to be most successful at helping people repay Tarp who might not otherwise be able to," says Ralph "Chip" MacDonald, a partner at Jones Day in Atlanta. "And it kicks the can down the road."

But it appears that only about a quarter of the small banks that were in Tarp when the SBLF opened earlier this year will actually convert to the new program.

Overall, more banks were rejected by the SBLF than were approved, according to Paul Merski, executive vice president and chief economist for the Independent Community Bankers of America. The available data suggests that the same trend holds for Tarp banks.

The poor economy has hurt bank profitability, which has made it harder for banks to repay their Tarp investments, Merski says.

"It's very difficult for community banks to raise private capital, and I think that's a function of the economy," he says. "I think a lot of folks thought the recovery would be much more robust at this point."

Christy Romero, the acting special inspector general for Tarp, notes that many small banks have large exposures to commercial and residential real estate, two sectors that have suffered over the last few years.

"Developers are hard hit. And so that's where the community banks are," Romero says. "And so when the developers go into default, there can be an avalanche effect on these banks."

Romero would like to see the Treasury take a case-by-case approach to repayment by small banks, in contrast to what she described as the program's one-size-fits-all repayment terms.

She notes that the Treasury has been gathering a lot of information about Tarp banks, and that in some cases it has been sending observers to their board meetings.

"I think they really need to be talking to these banks, and talking to the observers that they're sending, and determining how to give these small banks a clear exit path," Romero says.

She also notes that in some instances the Treasury has restructured its Tarp investments, taking a partial loss in order to avoid a total loss.

"So that same kind of consideration needs to go into, 'What's the ultimate strategy to get small banks out of Tarp?' " Romero says.

Barofsky predicts that as the eventual rise in Tarp's dividend rate approaches, the Treasury Department will agree to take partial losses on its investments in small banks as part of sales and merger deals.

"You're going to see mergers, you're going to see acquisitions," he says.