-

Executives from Wal-Mart, 7-Eleven and McDonald's are raising concerns that the new debit-fee regulations they fought for are unlikely to boost their bottom lines.

November 8 -

The bank wanted to be up front with consumers about its short-lived debit card fee, senior executive Laurie Readhead said. She acknowledged a lack of initial planning, saying B of A has "a lot to learn."

November 3

This is an updated version of an earlier story.

The business of issuing prepaid debit cards to the unemployed and disabled is one that has emerged from the financial crisis virtually untouched by the flood of new regulations. Even so banks — led by Bank of America Corp., JPMorgan Chase & Co., U.S. Bancorp and Wells Fargo & Co. — are navigating with caution the relatively small but fast-growing business of running these state-run benefit programs.

Given that banks have already become lightning rods for the public's financial frustrations, their participation in the state benefit business brings with it the added risk of antipathy among the unemployed, disabled and consumer advocates who are increasingly sensitive to being charged bank fees of any kind, especially for receiving public benefits.

Prepaid government benefits cards have been around for many years and were deliberately exempted from the federal rules capping debit transaction fees that went into effect Oct. 1 as part of the Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act.

That exemption received strong backing among state government officials, who argued that it was necessary to leave the benefit cards' interchange fees uncapped so that banks could recoup the costs of running the programs.

State benefit payment operations "are fast-growing but thin-margin programs for the banks, and they are restricted (by states) in the types of fees charged to consumers," says Madeline K. Aufseeser, a senior analyst with Aite Group.

Banks generate revenues from government benefit programs in three ways: the interchange fees that merchants pay; fees charged to benefit recipients for services like frequent ATM withdrawals; and the float earned on benefits sitting in users' accounts.

Cash-strapped states increasingly are turning to banks to run their benefits programs as a way to eliminate the cost of issuing paper checks, mailing them and incurring fraud losses. For benefit recipients who don't have bank accounts, prepaid bank cards eliminate the need to pay check-cashing fees, which states claim is a major benefit of their card programs.

The benefits-card business has also grown relatively attractive to banks as the ranks of the unemployed have swelled and they brace for the loss of billions of dollars in interchange fee revenue in their conventional debit card businesses.

With state benefit cards, banks typically charge merchants 1% to 2%, or an average of 44 cents, per transaction (amounts vary, depending on the merchant's relationship with the bank). By contrast, under Durbin banks can only charge no more than about 24 cents per transaction to merchants whose customers are not using state benefit cards.

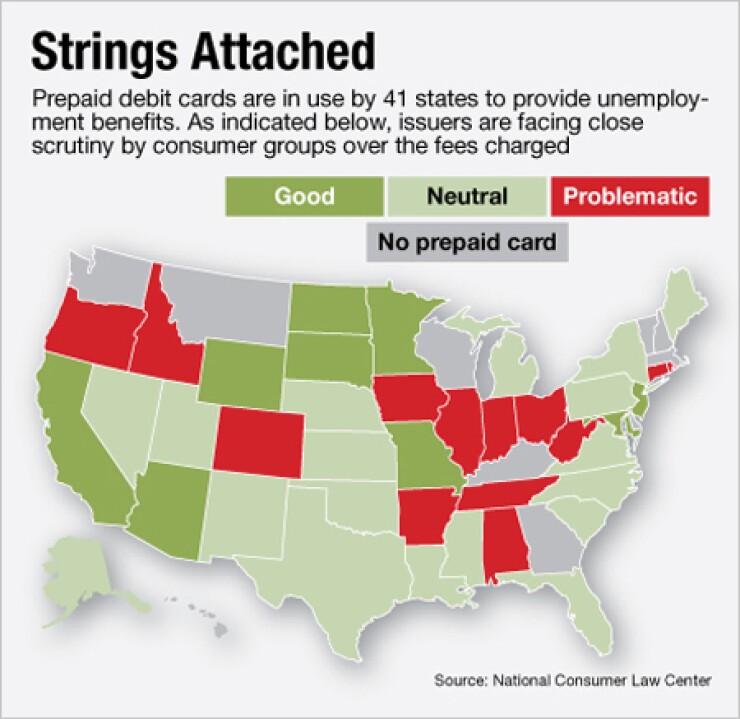

As the number of states using bank cards to distribute benefits has grown to 41, some practices have come under particular scrutiny. A handful of states, for example, have negotiated terms under which the banks managing their card programs cut them in on a portion of the revenues generated.

California negotiated what officials there call a "no-cost contract" with Bank of America Corp. for its $27 billion (2010 benefits paid) jobless and disability card program. State officials say beneficiaries using the cards can avoid all fees with careful use. Fees do apply in some cases, however, such as when a recipient exceeds the four free non-B of A ATM withdrawals permitted each month.

The state receives a percentage of revenue from B of A, based on the average daily balance on benefit cards in circulation, says Sabrina Reed, chief of California's unemployment insurance integrity and accounting division. The revenue that B of A passes along to the state is generated entirely from interchange fees, she adds.

"Everybody wanted to land the California contract because of the volume," says Reed, adding that the state issues unemployment and disability benefits biweekly to two million recipients. "If you have millions of cards out there and people are swiping the cards, the bank is earning money."

California has received $7.7 million from B of A since December 2010, when it began rolling out prepaid cards for the disabled, according to Reed. The state began switching the unemployed to B of A cards in July 2011, and finished the transition this month.

The fact that banks can afford to hand over a portion of their interchange revenue to states raises the question of whether the Durbin exemption for government prepaid cards was necessary at all, argues Lauren Saunders, a managing attorney at the National Consumer Law Center, which issued a report in May grading state-issued debit cards on the basis of the cost and quality of services for beneficiaries. (California received a "good" rating.)

"Some states have demanded revenue-sharing and that is completely unacceptable...they are profiting off the unemployed," Saunders says.

Steve Streit, chief executive of prepaid marketer Green Dot Corp., says that given the costs to banks of running benefit card programs, limiting banks' revenues entirely to interchange fees does not provide much of an incentive to stay in the business.

"I don't think interchange alone is that profitable," says Streit. "It all depends on the cost basis of the bank."

Aite Group's Aufseeser says government cards programs generally "are profitable but with very low margins."

That helps explain why many of the states let the banks running their benefits cards impose user fees, primarily for non-network ATMs and overdrafts.

Banks and states emphasize that unemployed and disabled recipients receive voluminous notifications about how they can avoid such fees. Even so, they continue to pose the risk of inciting a public outcry.

"Nowadays people are very sensitive to fees of any kind," says Green Dot's Streit. "The bank product [states are] issuing is from a civic institution, so to charge fees that some may consider suspect invites negative press, critique and anger."