-

The Federal Reserve's decision to keep federal fund rates at near zero levels until 2013 has sparked some concern by observers that banks could be in for more agony in the near future.

August 9 -

At least part of the price tag is in for Hudson City Bancorp's spat with regulators: 7 cents a share.

April 20

The Federal Reserve's vow to keep interest rates low for another two years has taken a number of bankers by surprise.

The Fed's unforeseen — and unprecedented — commitment to keep rates low until 2013 is forcing banks of all sizes to rethink the way they manage their balance sheets. The declaration is forcing some bankers to make a U-turn after they'd began restructuring their balance sheets earlier this year in anticipation of higher interest rates.

Even banks with "neutral" interest rate risk positions, such as Trustmark Corp. in Jackson, Miss., were taken aback by the stance. Trustmark had modeled in low rates through 2012, but the added year of low rates may throw off its calculations.

"What surprised us was how specific the Fed was for the durations," says Gerard Host, the company's president and CEO.

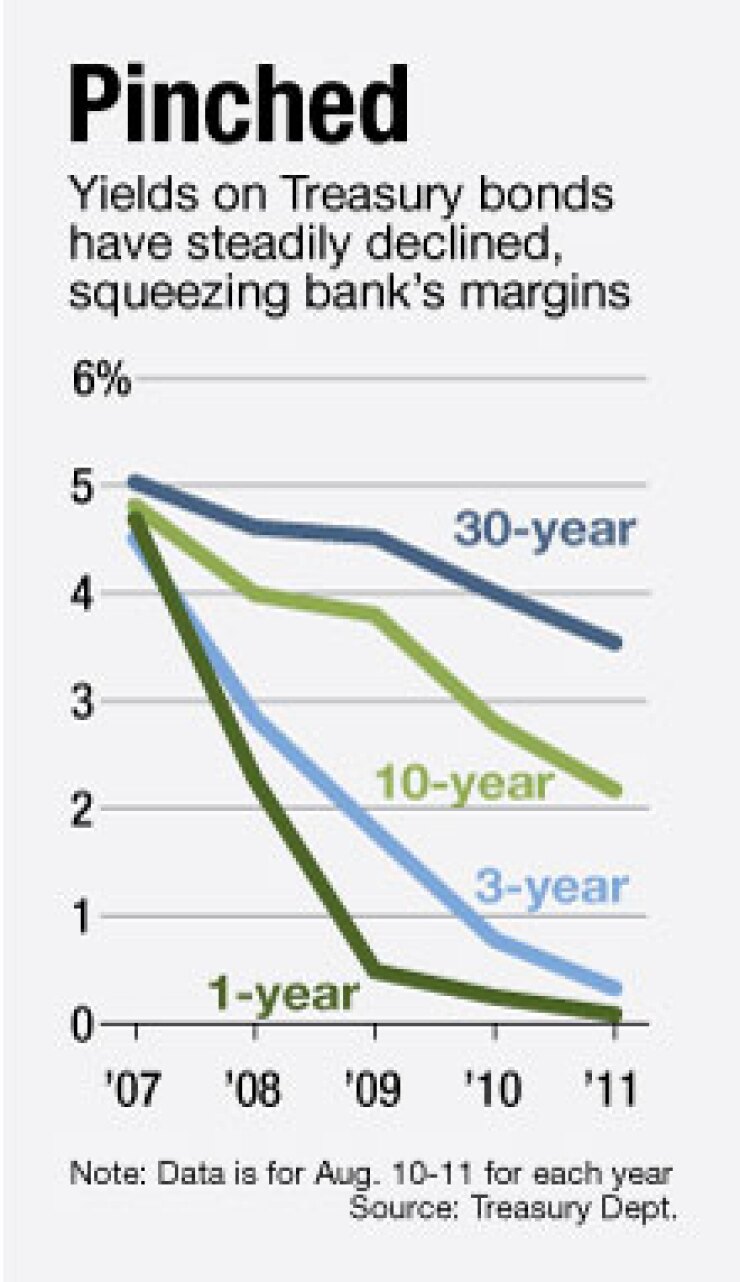

Many bankers were expecting anemic economic growth in the near term, consigning themselves to investing in Treasury bonds and related securities to get some semblance of a yield. Now, those yields seem set to remain razor thin for the foreseeable future.

The situation has John Corbett, the president and CEO of CenterState Bank of Florida in Davenport, quoting the Johnny Cash song "Sunday Morning Coming Down." He likened investment in government bonds to wearing "my cleanest dirty shirt," given a dearth of alternatives.

The Fed's decision "just makes it that much more obvious that it's tough for some institutions to make any money or generate a decent return," says Michael Perry, the chairman, president and CEO of San Diego Trust Bank. "You will be seeing a number of mergers and transactions taking place that you wouldn't otherwise see."

Banks may be unable to expand net interest margins until 2014, if rates stay low through mid-2013, according to a note Thursday from the reasearch team at Evercore Partners. A concern is that banks will have to reinvest cash flows from maturing mortgage-based securities into low-yielding bonds.

Another issue is lending. The Evercore team wrote that a "persistently low" rate would put pressure on pricing for mortgage loans and "indirectly influence overall loan yields."

Among the banks that had started to prepare balance sheets for a steady interest rate rise is Hudson City Bancorp Inc. The Paramus, N.J., thrift company completed a large restructuring in March to lower risk to higher rates in response to a regulatory order. The $60 billion-asset company took a $644 million charge during the first quarter related to the deleveraging.

Now that any rate rise has been pushed down the road, analysts are questioning the necessity of the company assuming such immediate financial pain. Calls to Hudson City were not returned.

"That is an unfortunate situation for them," says Mark Fitzgibbon, an analyst at Sandler O'Neill & Partners LP. "In the short term, it's a little painful."

Even so, viewed more broadly the Fed's low-rate declaration is a plus for banks since it adds an element of clarity to excess cash investments. "People were paralyzed by the uncertainty," Fitzgibbon says.

Some bankers wonder whether the Fed will keep its low-rate vow. Bankers like Corbett are turning to low-yielding Treasury bonds while aggressively seeking out a handful of standout commercial loans from which to generate earnings. "All the shocks to the market … [are] scaring people," he says.

With loan demand soft, a pricing war over commercial lending is likely to get even more fierce amid the rate freeze. Bankers can only go so low on rates before investing in securities starts to look like a higher-yielding — option.

Long-term Treasury yields have dropped as banks rebalanced investment portfolios after Standard & Poor's downgrade of U.S. debt and the ensuing stock market volatility.

"When the market is disrupted, there is a flight to quality, and that's why we have seen an uptick in Treasuries" prices, says Craig Miller, who co-chairs the financial services group at Manatt, Phelps & Phillips. "Is it meaningful enough to have an increase in … margins for community banks? I don't think so."

Given low Treasury yields, observers say larger community banks are even considering investing in corporate bonds.

"It's harder to hold those securities in a portfolio," since they are subject to higher capital requirements than Treasury bonds, says Michael Reed, a partner at DLA Piper in Washington. "They're trying to diversify."

Bankers are continuing the quest to lower the cost of funds, which means that deposit rates are likely to continue falling.

"We still have some room to bring rates down" for deposits, Host says. "There will be no knee-jerk reaction right now. The markets are so volatile that we just have to stay our course and continue to find good quality loans."

Host says he's likely to keep expanding Trustmark's investment portfolio to compensate for "lethargic loan growth."

Even as banks grapple to respond to the Fed's low-rate proclamation, they show understanding for the necessity of such a move.

"You know the economy couldn't withstand higher interest rates," Perry says. "Plus, the Fed needs to keep rates down because we still have deficits as far as the eye could see to finance."

Others question the long-term cost to banks of a low-margin lending and investment environment.

"I don't think politicians give a damn about banks and their earnings," says Jeff Davis, an analyst at Guggenheim Securities. The Fed is "spooked about an emerging banking crisis in Europe, with both a liquidity crisis and solvency crisis, and keeping rates at zero will help indirectly fight that fear … but it comes at a cost to savers and many banks."