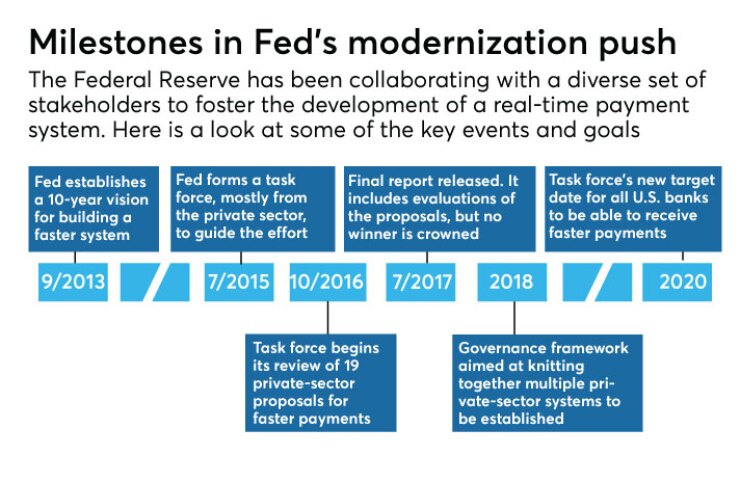

A panel convened by the Federal Reserve has established an ambitious new goal: By 2020, anyone with a bank account in the United States should be able to receive payments that are highly secure and delivered in something close to real time.

The three-year target is disclosed in the final report of a task force organized by the Fed two years ago. Its members include representatives of big banks, small banks, technology companies, consumer advocacy groups and government agencies.

The group’s responsibility was the modernization of the nation’s aging payments system. The U.S. has fallen behind the U.K., Sweden and a host of other countries that enable real-time payments between any two bank accounts.

Unlike many other countries, the Fed is trying to encourage payment system upgrades without imposing a government mandate for specified improvements on the nation’s banks and credit unions.

American Banker obtained

“While the eventual number of solutions in the market cannot be predicted, it is desirable to broaden the reach of all solutions by enabling faster payments transactions to cross between them,” the 63-page report states.

So the report recommends the development of a framework for governance of a faster system that would feature multiple competing products. To accomplish that work, the task force recently elected members of a new working group, though its membership roster is not expected to be announced until August.

The eventual governance framework might be run by a new private-sector entity that resembles Nacha, the banking industry group that sets the rules for the automated clearing house network.

“These cross-solution rules and standards would encompass a baseline set of requirements that enable payments to move securely and reliably between solutions, and ensure end users have predictability and transparency in certain key features pertaining to timing, fees, error resolution and liability,” the report states.

The report also recommends the establishment of a look-up directory that would enable individuals and businesses to send money from one fast-payment system to another.

In addition, the task force calls on the Federal Reserve itself to develop a settlement service — this refers to the process of two banks settling up after a transaction is executed — that operates 24 hours a day and every day of the year.

On Monday the Fed plans to issue a statement about the task force’s report, and the central bank expects to provide a more detailed update in early fall, said Sean Rodriguez, faster payments strategy leader for the Federal Reserve System.

In an interview, Rodriguez was complimentary of the collaboration among private-sector firms, which culminated in the task force’s recommendations. “Those are some pretty demanding calls to action, and will certainly drive the discussion and focus over the coming years,” he said.

As part of its work, the central bank-led task force developed

Proposals were submitted by a diverse swath of the private sector, including San Francisco-based Ripple, Des Moines, Iowa-based Dwolla, and even

But most of the plans have been overshadowed by a joint proposal from The Clearing House, a payments company owned by the nation’s largest banks, and the financial technology company FIS.

Some competitors fear that this fledgling system, which is further advanced than many of the others, will become dominant because of the size and the power of the companies that are backing it. Small banks are particularly concerned that they will have to rely on a system where the pricing, rules and processes are determined by megabanks.

The task force’s report highlights a few challenges that will have to be overcome to achieve the group’s goal of enabling all banking customers to receive fast payments by 2020. (A Fed white paper from 2013 envisioned a 10-year time frame, but industry officials pushed for speedier implementation.)

One concern is that some companies will not want to participate in a collaborative effort. These firms could decide to focus on building the reach of their own offerings rather than interoperability, at least initially.

There is also the possibility that technological differences, such as divergences in how payment disputes get resolved, will serve as a barrier to collaboration.

Another potential pitfall mentioned in the report is that whatever private-sector services are eventually offered will fail to achieve broad adoption.

This concern is particularly acute in the United States — which is home to roughly 12,000 banks and credit unions, and where the payments landscape is increasingly fragmented — given the fact that the Fed is playing a less forceful than central banks have in other countries.

“The biggest issue I think in the United States is the sheer number of banks,” said Laurence Cooke, CEO of nanoPay, a Toronto-based payments company that submitted a proposal to the Fed’s task force.

He added, “We will all collaborate.”

If the U.S. does end up with multiple faster payment systems, the competition that is created will be beneficial, said Elizabeth McQuerry, a payments consultant with Glenbrook Partners.

But the system could also create confusion among members of the public and add layers of complexity, which will make the endeavor more costly, she added. “What we really need I think is a scheme that brings these services together.”

Members of the Federal Reserve’s task force