WASHINGTON — Three years after being launched at the height of the financial crisis, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.'s blanket coverage of no-interest deposits is still in effect, but its mission has radically changed.

An idea originally meant to help community banks has become a double-edged sword at the largest institutions, which have seen their large-deposit inflows swell with investors - nervous about recent economic shocks — rushing to safety.

But whereas banks initially relied on the expanded FDIC insurance for stability, after the Dodd-Frank Act extended the coverage until the end of 2012, many large banks have been left with billions in ultra-short term money with limited benefit and added costs.

"It was really intended for small banks … and for the protection of businesses to make sure they wouldn't suffer losses," said John Douglas, a partner at Davis Polk & Wardwell and a former FDIC general counsel. "Now we don't have liquidity issues, and banks don't need funding. This aspect of it, large institutional investors moving into noninterest bearing transaction accounts simply for safety, in a sense is probably beyond what the FDIC was thinking — beyond the needs of the crisis."

The FDIC reported that most of last quarter's deposit growth was attributed to large-denomination deposits, including accounts receiving the full FDIC coverage. Domestic deposits in accounts greater than the standard $250,000 FDIC limit increased by 8.8% — or by $279.6 billion. (Total domestic deposits only rose by $234.4 billion.) Meanwhile, totals of noninterest bearing deposits above the standard limit receiving full FDIC insurance rose by a whopping 15.4%, or by $161.8 billion.

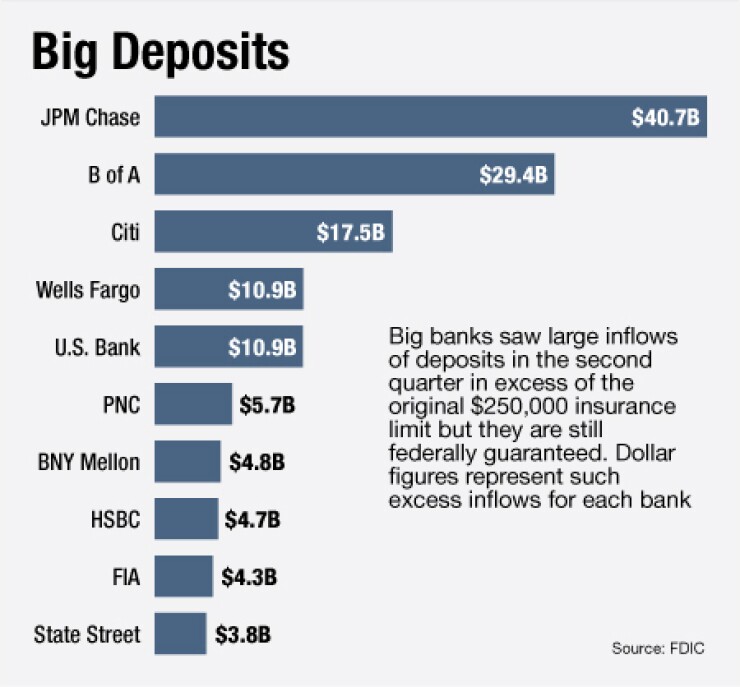

While institutions of all sizes are seeing more noninterest bearing deposits, large deposits grew disproportionately at the biggest banks, most of them fully guaranteed.

The number of no-interest deposits that were completely guaranteed rose by nearly $128 billion at the 19 largest banks, led by a nearly $40.7 billion inflow at JPMorgan Chase & Co.'s largest bank, and $29.4 billion in growth at Bank of America Corp.'s largest bank. Inflows of large deposits also included those without the full guarantee. At Bank of New York Mellon, deposits above the $250,000 limit increased by nearly $35 billion.

Large inflows are also said to be occurring this quarter, which has seen sharp stock-market volatility amid Standard & Poor's downgrade of the U.S. credit rating and deep concerns about the European economy. (The FDIC's data is as of June 30.)

Giving institutional investors peace of mind is a different goal than regulators' envisioned when the blanket coverage was announced in October 2008. Then, the guarantee was to combat concerns that depositor fears about bank health could threaten liquidity. The FDIC used its own authority to provide the full coverage just to banks that wanted it and would pay a premium surcharge.

The program was most useful to community banks, which could use the coverage to prevent business customers with transaction accounts above the standard insurance limit from going to large banks that were presumed "too big to fail."

Initially, the program, paired with a temporary FDIC guarantee of bank debt, was to last one year, but the agency implemented extensions to avoid a cliff effect for small institutions. Under Dodd-Frank, the coverage is mandatory for all institutions, no longer includes a surcharge, and expires at the end of next year.

Camden Fine, the chief executive of the Independent Community Bankers of America, said some small institutions would like to see the coverage prolonged even more, although any efforts to extend are not currently on lawmakers' radar.

"It's a mixed bag. There are regions in the country where community banks may favor an extension. There are also regions in the countries where community bankers would not favor an extension," Fine said.

But now, although the blanket FDIC insurance may calm investors opting for a complete government guarantee and many community banks still like the program, it is becoming a headache for large banks. Not only does the huge influx of funding carry a burden associated with deposit insurance premiums, but they must invest the deposits in new assets, driving down leverage ratios.

"It could clearly have an affect on deposit insurance premiums. Even a temporary hiccup can have a deposit insurance impact," said Mark Schmidt, a managing director at Promontory Financial Group and a former Atlanta regional director at the FDIC.

And since the money is likely to be withdrawn quickly, either when the economy improves or the full guarantee expires, that limits banks' options to invest the funds.

"You can't really invest it and you can't lend it out, other than overnight, because that money may flee," said Ron Glancz, a partner at Venable LLP. "Banks are in a quandary. They're paying the premiums but they're not really getting the advantage of increased deposits. … Since you don't know when that money is going to leave the bank, you're really restricted."

Large banks have recently discussed the impact with regulators, although it is unclear whether they will provide any relief. Observers said it is unlikely the FDIC would provide any premium discount for the large deposits, and even though the inflows have a small downward effect on capital ratios, it is not enough for any bank to lose its "well-capitalized" status.

"We've certainly reached out. We know banks have reached out. We know the regulators have reached out. … Unusual events require these conversations and that's a very good thing," said James Chessen, the chief economist at the American Bankers Association.

An FDIC spokesman said the premium impact from the large deposits may be small if depositors are holding them for short periods of time, since a bank's assessment is not reflected in just a snapshot of its liabilities, but as an average of the daily balances each quarter. "Because we use average daily assets, deposits held for" short periods "will have only a corresponding small effect on average daily assets and, therefore, insurance premiums."

Meanwhile, while banks generally have received heightened scrutiny for any reduction in their leverage ratio, regulators are not likely to criticize reductions tied to these deposit inflows. Leverage ratios have largely remained above 5% — the trigger for losing the "well-capitalized" mantle — and international capital rules calling for higher ratios have not yet been implemented.

"I am not sure how the FDIC would make exceptions for those deposits" in pricing premium, Schmidt said. "It would be tough to decide which deposits would meet the definition for the exception and which would not."

But in terms of capital ratios, he added, "I can see a regulator allowing a little bit of flexibility in that case as long as the bank maintains its well-capitalized status."

A spokesman for the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency said the agency recently discussed with the seven largest banks the impact of increased deposits on leverage ratios in the third quarter, but that the agency is not overly concerned.

"This is seen as a signal of the world's confidence in large U.S. banks based on their position of strength. The money is generally from large professional money managers and was moved in large blocks, which means it can also leave in large blocks quickly," the OCC spokesman said. "While the large flows may have some impact on large banks' Tier 1 capital leverage ratio, it will not approach the 5% level because the large banks are extraordinarily well capitalized at historic levels. Because of that, they don't need capital relief."

Still, observers said the added funding does not afford the industry any real growth opportunities. A likely use of the deposits by banks is to place them in excess reserves at the Federal Reserve banks, leaving institutions with small returns on their assets.

"What are they going to do with the money to earn a return to make up the cost when the deposits are so huge and loan demand is not what it was? You may just want keep it at the Fed, but you're earning peanuts on that money and you have to pay for the FDIC insurance," said Michael Bleier, a partner at Reed Smith and a former general counsel of Mellon Financial Corp.

But despite large banks' concerns, Douglas said they might be stuck with the policy of full coverage for no-interest transaction accounts even past the 2012 expiration deadline if lawmakers fear the effect of taking it away all at once from those who value it.

"It will be interesting to see whether this genie actually gets put back in the bottle," he said. "If I were betting, my bet is that it would be extended. That's mostly because it's such a benefit to the small banks, and there are so many small banks."