-

State Bank Financial's (STBZ) second-quarter earnings nearly doubled what it reported a quarter earlier as the serial acquirer's organic growth outpaced growth from acquisitions.

July 30 -

The California company received the FDIC's blessing to sell 11 loans covered by loss-sharing arrangements. Industry observers believe more sales could take place now that this deal has been cleared to take place.

July 20 -

FDIC loss-sharing deals are significantly down this year as failures get smaller, bidders become more competitive and the economic situation improves.

July 2

Banks that built up balance sheets in the earliest days of the financial crisis by buying failed banks are facing a ticking clock to unload loans they gained from those transactions.

Many failed-bank acquirers are nearing expiration dates for loss-sharing agreements with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. The agreements typically last for five years on commercial loans and 10 years for residential loans.

That means that FDIC coverage would run out next year on commercial loans associated with 2008 bank failures.

"Everyone is concerned about what happens as commercial loss-sharing starts maturing because prices haven't [rebounded] like everyone thought they would," says Chip MacDonald, a partner at Jones Day. Failed bank buyers "want to dispose of as many loans as they can and get the loss-sharing before it ends."

In fact,

As coverage and collections fall, so do a bank's revenue from loss sharing. If failed-bank buyers want to continue wowing investors, they must work harder to get recoveries from the covered loans and make new loans to bolster the asset side of the balance sheet.

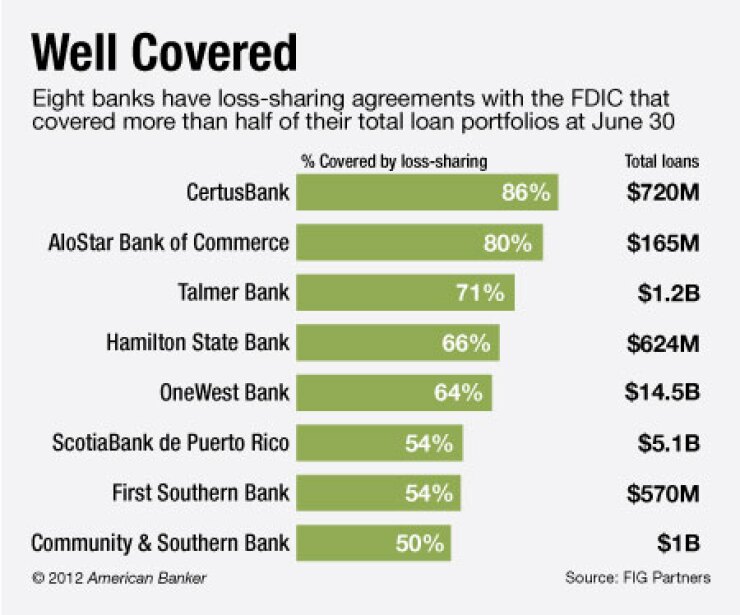

"Loss share is not a hobby; it's a line of business," says Patrick Frawley, the chief executive at Community & Southern Bank. The Atlanta bank has 14 loss-share agreements from buying seven failed banks. Half of the bank's loans consist of covered loans, according to FIG Partners.

"It's a constantly changing dynamic," Frawley says. "One portion of the portfolio is shrinking because you're turning collateral back into cash [from liquidating loans] and another portion is shrinking just from refinances and payoffs."

The $2.2 billion-asset bank is adding loans but declines in covered loans have offset overall loan growth. Other failed-bank buyer are facing similar challenges.

"We're doing as much internal growth as we can," says Norman Skalicky, the chief executive of Stearns Bank in St. Cloud, Minn. "There are an awful lot of people looking for loans and there are not as many new loans getting done so a lot of people are fighting for that business."

Like Community & Southern, Stearns separates its loan officer group from its failed-bank resolution group. "It's a lot of work so it's hard to find a lot of people who want to work those loans and work hard at them," Skalicky says. Since 2008, the $1.3 billion-asset bank has acquired eight failed banks.

Skalicky said failed-bank deals helped offset weak loan demand, making up about 30% of its $1 billion loan book. Unfortunately, there are few performing loans in a failed bank's portfolio.

Stearns bought a pair of failed banks in Florida in August 2009, adding $425 million in loans. That number has dropped to less than $200 million largely because of write-downs, settlements and borrowers paying off the loans.

Bankers know that, once the loss-sharing expires, any failed-bank loans left are their sole responsibility. Even the healthiest loans often run a greater risk of being classified in the future, compared to those originated by the failed-bank acquirer.

"We have [failed bank] loans that are paying and performing but it's not a very good loan" due to the structure, Frawley says, including a lack of interest-rate floors for some loans. "We also find that while some of these loans are paying today, they may not be paying tomorrow or the next year."

It is fair to wonder whether these deals will fully pay off for acquirers. Bankers say that, for now, they have received a nice earnings boost because of loss sharing. And some buyers almost see it as a civil service to help clean up the mess.

"Somebody has to work those loans and the FDIC … would prefer to keep them in the private sector," Skalicky says. "We feel it's a good thing to be doing and we also get some earnings out of it."

These bankers also realize that there is little long-term benefit to holding onto the loans, so they are trying to shift more resources to making new loans.

"Most of these banks are promoting new lending generally but there may be lag between new profits and the profits they had on the loss-share," MacDonald says. "The earnings may be at a lower level, but they will certainly be more stable once the loss-share rolls off."