-

Local governments have historically relied on selling bonds to finance operations. But low interest rates and the rising costs of taking bond issues public are making traditional loans a more tempting option.

April 13 -

-

Ten Virginia banks bound by an unusual holding company structure are merging into a single bank that would be among the largest headquartered in the state.

August 1

Worth Harris Carter Jr. has a great story to tell about his company, Carter Bank & Trust in Martinsville, Va., though he seems reluctant to share it.

By any measure, Carter, 77, is an extraordinarily successful community banker. He is also one of the most tight-lipped operators in the business. He makes no appearances at investor conferences, has seemingly never held a conference call and lacks a LinkedIn profile. He rarely agrees to interviews. In keeping with past practice, Carter Bank declined multiple requests to comment for this article.

The perplexing thing is that Carter has compiled a resume most other bankers would be more than comfortable discussing. It is no stretch to say that, if Virginia had a banking hall of fame like those in Texas, North Carolina, Illinois and Pennsylvania, Carter might be considered a shoo-in for admission.

The bank's executives "make themselves pretty scarce," said Philip Timyan, a shareholder who also pens a blog, Timyan Community Bank Alert, focused on financial industry investing. "They don't return calls, but if you write them a letter, you have a better chance of getting it answered."

That suits Timyan just fine. "I still like them and the way they run their bank," he said.

The $4.7 billion-asset bank traces its origins back to a single office in Rocky Mount, Va., that opened in late 1974 as First National Bank. Over the next three decades, Carter's strategy was to open community banks in underserved, largely rural communities in Virginia and North Carolina. Each had its own charter, with Carter himself serving as the key unifying element as chairman and president of each bank.

Carter's best work may have come in the past seven years. At the end of 2006, he

By most metrics, Carter Bank emerged from the recession stronger than ever. Since the end of 2007, loan losses have been minimal while profits have grown at a combined annual rate of 14%, topping $33 million last year. The bank has never had a losing quarter since the charter consolidation, including an $8.5 million profit in the first quarter of this year.

Over the same period, it has grown assets at an 8.3% annual pace, all of it through organic growth. Since the charter consolidation, Carter Bank has never so much as done a branch purchase, much less a whole-bank acquisition.

One would expect a bank that achieved those kinds of results would want to crow about it, but Carter is tighter with marketing dollars than he is with his own media profile. The bank spent just $262,000 on advertising and marketing expenses last year, significantly less than most banks of its size.

To give an idea of just how little the bank spends in relation to its peers, consider this: The $5 billion-asset Towne Bank in Virginia Beach spent $5.2 million on marketing in 2014, while the $3.4 billion-asset Cardinal Bancorp in Tysons Corner, Va., spent $5.1 million.

Carter does not budget much time for investors, either.

Scott Koonce, managing director at Montgomery Investment Management, said he began investing in the bank shortly before its charter consolidation. He figured the act of combining 10 small banks into a single institution would attract additional investors and a higher-profile listing.

"I thought wrong," Koonce said. "They're still on the pink sheets nine years later."

Koonce isn't too disturbed. The bank pays a regular, healthy dividend and its stock has performed well, rising 59% the last five years. "The returns haven't been outsized, but it's conservatively run and well-capitalized," he said.

The bank's loan book totaled $2.3 billion at March 31; its loan-to-deposit ratio was 55%. About 15% of those

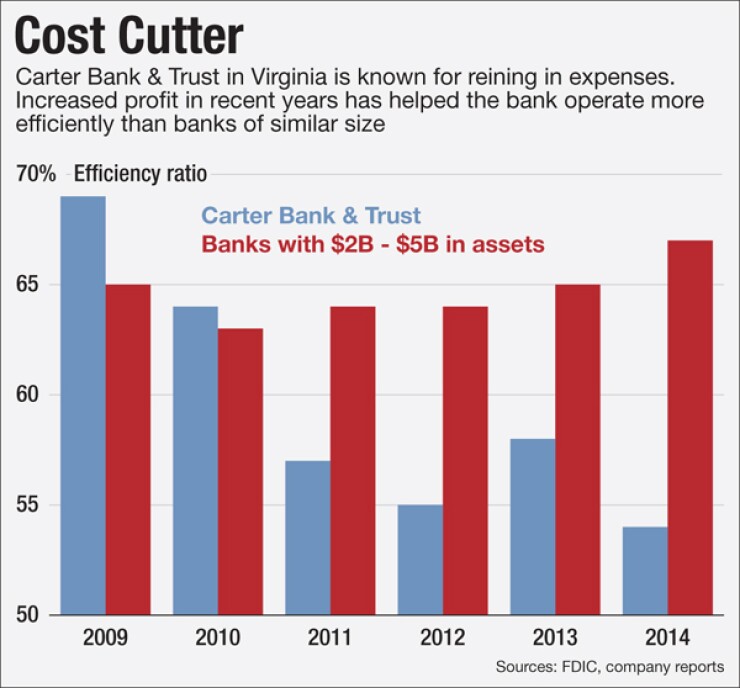

Carter Bank's numbers look "pretty good" relative to its peers," said Anita Gentle Newcomb, a banking consultant who serves on the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, adding that the bank does an exceptionally good job of managing expenses.

Indeed, Carter Bank's efficiency ratio is significantly lower than the average for similarly sized banks. Carter himself is legendary for his frugality. Stories abound of his reluctance to spend money on fax machines, which resulted in branch employees asking other businesses if they could use theirs.

Jerry Falwell Jr., chancellor of Liberty University in Lynchburg, Va., got to know Carter well in the 1980s and 1990s, when his school received several large loans from Carter's banking group. Falwell said he has heard the stories about the fax machines, and he has seen Carter's penchant for thrift up close.

"He drives a modest car with a lot of miles on it," Falwell said. "He reminds me of Sam Walton, the way he drove that old pickup truck even though he was a billionaire."

While he rarely meets with investors, Carter has spoken of his affection for what he terms eyeball-to-eyeball banking. His seeming disdain for technology extends beyond fax machines. Carter Bank lacks online banking and bank-owned ATMs. To avoid fees, the bank advises clients to take advantage of retailers' cash-back offers whenever possible.

Management has said that it is considering adding online banking but it has held back from introducing it due to security concerns.

Though she called the business model interesting, Newcomb sounded skeptical about the bank's ability to maintain it over the long term.

"Customers are demanding 24/7 convenience and are rapidly adopting online banking and mobile banking, including remote-deposit taking," Newcomb added. "Under Carter Bank's model, if you want to make a deposit, you have to go to the bank. That might work today, but over time I don't think it's a smart strategy."

As things stand now, the bank's customer base doesn't seem to mind the absence of online banking or ATMs. The bank has no brokered deposits and appears to have no trouble raising funds locally. Deposits totaled $4.3 billion on March 31, a 1.3% rise from a year earlier. The number of deposit accounts is growing as well, going from 332,000 to 340,000 in the past two years, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Such success seems linked to Carter's decision to focus more attention on his core responsibility: Managing a growing and profitable community bank with very little risk. Still, it's a trade-off, and like any trade-off it has a cost. By his reticence, Carter appears to be sacrificing the extra dollop of value that accrues to banks that execute effective marketing and investor relations strategies.

Making the situation more perplexing, the individual who stands to gain the most from the bank adopting a more forthcoming approach to communication is Carter himself. In addition to being the bank's founder and namesake, he is the biggest individual shareholder, with 3.2 million shares, or 12.3% of the outstanding stock, according to a May 22 regulatory filing.

Noted shareholder activist Gerald Armstrong, who owns a small stake in the bank, said Carter is unlike any CEO he has encountered. He said the bank's corporate governance policies were a cut above many of the companies he follows, making Carter's low public profile all the more baffling.

"I can't figure him out," Armstrong said. "I don't know why he is so withdrawn. He seems to have no profile at all."

Carter might be a mystery to his bank's institutional investors, but his clients see him as a much more sympathetic figure. Falwell said his school, which serves more than 13,500 students, would never have grown as it has without the $20 million loan from Carter's banking group in 1997.

"He believed in Liberty when no one else did," Falwell said. "I wish there was a way to train bankers to be like Worth Harris Carter. He's one of a kind."