Banks that specialize in loans to oil and gas companies are anticipating a rebound in demand for new financing — even as federal regulators warn about the risks that climate change poses to financial stability.

A run-up in prices since the start of the year has fueled higher expectations at a handful of banks that have remained in the sector.

Zions Bancorp., for instance, expects to push its $1.9 billion book of energy loans to $2.5 billion over the next year and a half. Such growth would return the portfolio to its level before the Salt Lake City company began shrinking the business following the collapse in prices between 2015 and 2016.

“At these prices, which were predictable, for both oil and natural gas, we will start to see drilling increase and you will see line utilization going up. And there are far fewer players today,” Zions Chief Operating Officer Scott McLean said during an Oct. 18 call with analysts.

The price for a barrel of WTI crude crested at $82 on Thursday, more than double where it was a year ago. Prices have risen as the economy reopened up and demand for oil has surged.

Borrowing bases, which are the amounts lenders are willing to offer in financing based on the underlying value of the oil and gas, have increased as well.

Most of the 84 energy lenders and oil and gas companies that responded to a September survey by the law firm Haynes Boone expected borrowing bases to increase between 10% and 40% this fall compared to the spring.

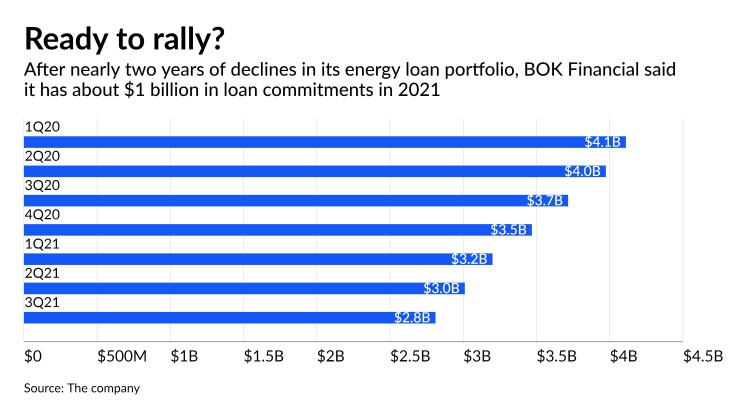

BOK Financial, a $46.9 billion-asset bank in Tulsa, Oklahoma, has already added 40 new oil and gas clients, along with about $1 billion in loan commitments this year. Its energy loans shrunk by about $1.3 billion between the first quarter of 2020 and the third quarter of this year.

Until now, energy companies have been using the climbing prices for their crude to pay down existing debt, but that’s about to change, BOK Chief Operating Officer Stacy Kymes said on an Oct. 20 call with analysts.

“Our current belief is that the fourth quarter will be the inflection point and we expect growth from this segment in 2022,” Kymes said.

The banking industry faces pressure from environmental groups, regulators and some lawmakers to reassess the role they play in financing oil and gas companies that contribute to climate change. Some larger banks, like Citigroup and Bank of America,

The Financial Stability Oversight Council, which has representatives from various regulatory agencies,

“It does not require a vivid imagination to see how climate change could threaten the financial system,” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said in public remarks Thursday.

“As climate change intensifies, more frequent and severe climate-related events — wildfires, tropical storms, and flooding, for example — could trigger declines in asset values and economic activity that could cascade through the financial system, especially if such risks are not properly measured and mitigated.”

The council’s report, which was ordered by the Biden administration in May, focused largely on the collection, analysis and disclosure of climate-related data.

During Zions’ third-quarter earnings call, McLean seemed to acknowledge that lending to oil and gas companies is politically fraught at the moment. He said that the $88.3 billion-asset bank has an appetite for energy lending before adding this caveat: “If I can say that without being politically insensitive.”

Some other banks that lend to oil and gas producers remain cautious about how dramatic the increase in new lending will be.

Drillers have become more reluctant to take on debt, given the years of major volatility in prices, said James Herzog, chief financial officer of Comerica Bank in Dallas, during the $94.5 billion-asset company’s Oct. 20 earnings call. He said that it may “take a little longer” for loan demand to pick up.

Just 18 months ago, when the COVID-19 pandemic shut down much of the U.S. economy, prices for crude briefly went negative, and oil traders were scrambling to pay anyone to hold their barrels amid a glut in supply.

“The commodity price run-up is not necessarily one that's going to just draw a whole bunch of capital to the space,” Herzog said. “The existing population is going to be the ones that are sort of navigating this price spike right now.”