E-commerce is wreaking havoc on brick-and-mortar retail sales, and the declining foot traffic is hurting many shopping malls, strip centers and Main Streets across the country. The rise in empty storefronts is understandably troubling for commercial real estate owners and the banks that lend to them.

But the great retail shakeout is presenting some new and interesting opportunities for commercial real estate lenders.

One is in financing the conversion of all that vacant retail space into new uses — restaurants, health clubs, medical facilities, community colleges, movie theaters and office space.

Another opportunity is financing the acquisition or construction of industrial warehouses and distribution centers. While the surge in e-commerce sales — expected to top $450 billion in 2017 and reach close to $700 billion by 2022 — has been a downer for retail real estate, it has been a boon to the industrial sector, and banks are actively searching for opportunities tied to warehouse and distribution.

“In the last 12 to 18 months, you’ve seen people come out of the ground with large, speculative warehouse space and, as fast as they can build it, it’s getting leased up,” said Patrick Ryan, the CEO of the $1.4 billion-asset First Bank in Hamilton, N.J. “We would love to continue to get our share of industrial loans.”

E-commerce’s impact on the retail landscape is just one trend commercial real estate lenders will be monitoring closely in 2018.

They will also be on the lookout for opportunities in residential construction, as the housing market continues to tighten and areas hard hit by hurricanes and wildfires look to rebuild. At the same time, they can’t load up too much on commercial real estate loans or they risk running afoul of regulators; and they need to be mindful about maintaining pricing discipline in the face of rising competition from nonbank lenders, insurance companies and deep-pocketed institutional and foreign investors. Here’s what to watch for in commercial real estate lending in 2018.

Logistics, logistics, logistics

One of the fastest-growing areas for CRE lenders is in warehouse and distribution, and that’s a trend that’s likely to continue in 2018 and beyond.

Simply put, the likes of Amazon, Zappos and W.B. Mason need massive amounts of space to store their goods, and they want properties to be very close to major population centers and transportation hubs so they can get products to customers within hours, not days.

“If you’re a bank and you want a new business opportunity, you better focus on anything that’s industrial or warehouse, and you better have lenders who understand the business,” said Peter Minshall, the managing partner at Washington Capitol Partners and a longtime real estate investor in the Washington and Baltimore areas.

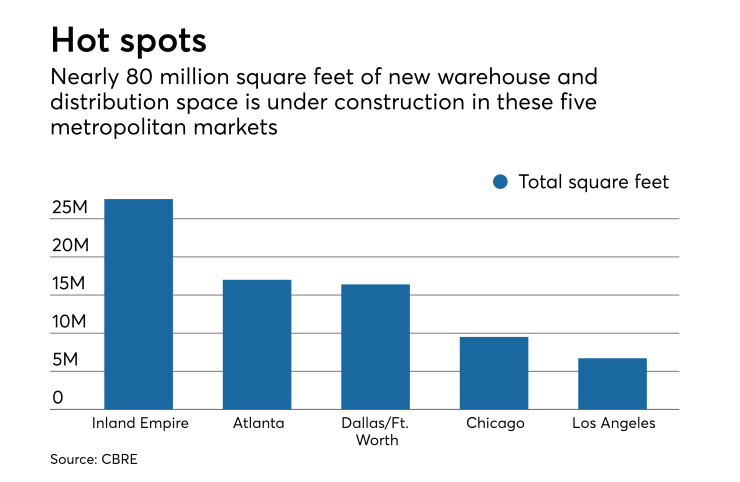

The trends are compelling. According to the commercial real estate firm CBRE, warehouse and industrial properties have seen positive net absorption — that is more space being leased than vacated — in 29 consecutive quarters, the longest such streak in more than 20 years. With demand soaring, warehouse vacancies are at near-record lows, rents are rising and building in the sector is booming.

In the Atlanta area, some 17 million square feet of new industrial space is currently under construction and in California’s Inland Empire, where the vacancy rate is a scant 1.3%, nearly 28 million square feet is being built, according to CBRE.

One of the most promising areas of industrial lending is in financing smaller distribution facilities that help online retailers complete the last mile of delivery, said Marc Thompson, director of the real estate industries group at the $5.7 billion-asset Mechanics Bank in Walnut Creek, Calif. The bank recently originated a loan for a “mini-distribution hub” for Amazon in the San Francisco Bay area, he said.

“The big semi trucks pull up and unload there,” Thompson said. “Then smaller vans come in, pick up that inventory, and make deliveries to communities. It’s not a million-square-feet warehouse. It’s more like 60,000 square feet.”

While most of the big players in e-commerce want state-of-the-art facilities, Scott McComb, the chairman, president and CEO at the $884 million-asset Heartland Bank, said that demand for older industrial properties is increasing as well, presenting opportunities for community banks like his.

Heartland, for example, has several clients in the microbrewing business that have taken over older industrial space, McComb said.

Minshall in 2014 was able to obtain a loan from a Maryland community bank to acquire a warehouse property outside of Baltimore that had been mostly vacant for several years. That facility, with more than 200,000 square feet, is now fully leased to W.B. Mason, an office-supplies dealer.

Whether it’s older properties or new construction, opportunities abound in industrial real estate and more banks want in.

Norm Nichols, an executive vice president at the $137 billion-asset KeyCorp in Cleveland, said that, while Key has financed some deals involving warehouse and distribution facilities, it intends to allocate even more resources to the sector over the next several years.

“We are in the industrial space, but we would like to be in it even more,” he said. “The fundamentals are likely to remain very healthy.”

The reinvention of retail

A reckoning is coming in retail real estate, and banks that hold the loans on all those half-empty malls and strip centers will almost certainly see a rise in delinquencies or defaults in the coming years.

Still, they can mitigate their losses by being opportunistic in working with developers to find new uses for those properties, said Byron Carlock, leader of the U.S. real estate practice at PwC.

'Retail going forward is going to be less about new development and more about reimagining existing square footage,' said Norm Nichols, the national manager for real estate project finance at KeyCorp.

Ford Motor Co., for example, recently moved nearly 2,000 employees to an abandoned Lord & Taylor store that had once anchored a suburban Detroit shopping mall. A six-store strip center outside of Columbus, Ohio, was recently acquired by a nonprofit ministry that converted the space into a health clinic and food pantry, in a deal financed by Heartland Bank in nearby Gahanna.

Nichols said that with the increase in vacant retail space, it is crucial for banks to foster relationships with developers who have experience in repurposing commercial properties that have become obsolete.

“Retail going forward is going to be less about new development and more about reimagining existing square footage,” said Nichols, the national manager for real estate project finance at Key. “We are actively looking for clients who have proven track records of being able to reinvent space.”

New home construction

The supply of housing, particularly in urban markets, is at a 20-year low, according to some estimates, but many banks remain reluctant to finance new construction for fear of eclipsing concentration limits imposed by regulators. At the same time, they are hopeful that new Trump-appointed regulators may ease up on some of the pressure they had placed on banks, said PwC’s Carlock.

“Since the crisis, banks have tightened their underwriting and criteria for construction lending,” he said. “The banking sector has underlent to good development opportunities out of fear of regulatory reprisal.”

The need for new housing is particularly severe in areas hard hit by natural disasters. Bankers and analysts estimate that hundreds of billions of dollars will be needed to rebuild in markets like Houston and Florida that were damaged by hurricanes, and the sections of California destroyed by wildfires.

Mechanics Bank is already

“There’s a huge need in that area,” he said. “We are definitely focused on gearing it up.”

Thompson noted that it may be late in 2018, or early 2019, before local governments begin issuing permits needed to rebuild single-family homes in areas hit by wildfires.

Some banks took steps in 2017 to limit their exposure to commercial real estate. The $6.6 billion-asset Dime Community Bancshares this month

First Bank in New Jersey may follow Dime’s lead and pursue a securitization of CRE loans next year, Ryan said.

“We like to bring in participants to share the loans with us,” Ryan said. “It helps us manage our ratios.”

Competitive threats

Of course, real estate is so hot these days that banks are often left on the sidelines when it comes to funding big deals.

Bo Cashman, a Baltimore-based senior vice president at CBRE, said that institutional buyers are so hungry for industrial properties and are so flush with cash that they don’t even need bank financing to acquire them.

On the construction side, the biggest warehouse user of all, Amazon, is building facilities that are so big and have such specific needs that only the largest banks and investment banks can participate in the financing — if Amazon needs financing at all.

“We have no shot at banking Amazon,” said Heartland’s McComb.

Then there is foreign capital. The influx of money from overseas sources, especially government-sponsored funds, has driven the price of some CRE deals to new levels. Much of the new financing has

Foreign capital, especially money from China, has become so prevalent in Southern California that some bankers don’t have to look far to find evidence.

“From our offices in downtown Los Angeles, we can look out our window and see cranes working on 15 projects that have Chinese money,” said Rocky Laverty, president of the $3.2 billion-asset Grandpoint Bank in Los Angeles.

In fact, the emergence of foreign capital may become one of the main stories for commercial real estate lending in 2018, Laverty said.

“There is so much new inventory coming on the market,” Laverty said. “When these projects are completed, they will add so many new units” of both residential and office space. “Who knows what the saturation point is?”