Everyone remembers the school bully, even in banking.

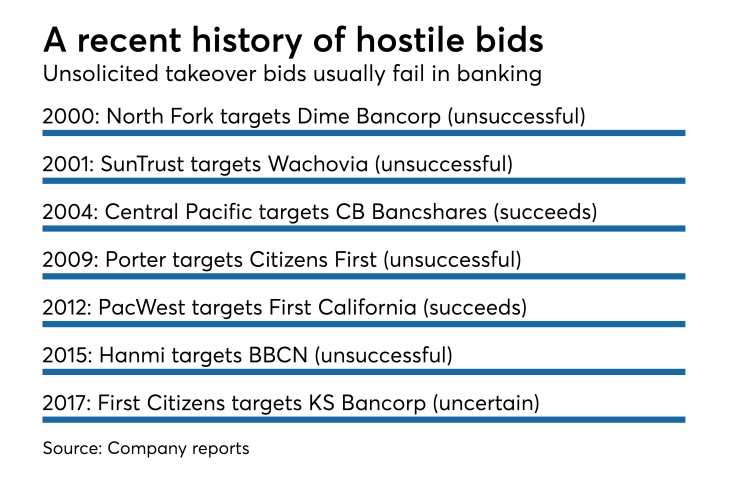

Hostile takeovers are so infrequent that they draw attention when they occur. They are often a matter of perspective: Targets feel they're being pushed around, while aggressors believe they are working around recalcitrant directors and management to pursue a justifiable goal.

Which view is right? It depends.

First Citizens BancShares in Raleigh, N.C., is the latest institution to make an unsolicited bid, taking an offer to buy KS Bancorp directly to the Smithfield, N.C., company’s shareholders.

The board at the $368 million-asset KS Bancorp has derided the effort as one that is “not in line with … community banking values.” The $34 billion-asset First Citizens, however, has defended its actions as being “fair and open” with KS Bancorp's investors.

The situation poses broader questions. Do aggressor banks increase their reputational risk by trying to force a deal? How do acquirers manage the message to a target’s shareholders and employees? What will other potential sellers think if they see a bank become aggressive?

As far as reputation is concerned, banks attempting hostile bids could face fallout “on the margin,” said John Gorman, a lawyer at Luse Gorman in Washington. At the same time, a bank that knows what it wants could appear more attractive to boards at other institutions looking to sell for the best price possible.

Aggressors shouldn’t have major problems persuading other banks to sell as long as they offer fair pricing as part of an unsolicited bid, said Tony Plath, a finance professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

Message is also critical, particularly when dealing with a target’s investors, industry observers said.

Directors have a duty to review proposals that offer premiums and boost shareholder value, said Jack Thompson, the head of financial investments at Gapstow Capital Partners in New York.

So an aggressor’s key objective involves making the case to a target’s investors that selling provides “an opportunity to realize better value, so don’t let management and the board get in the way of that,” Gorman said.

There are trade-offs to going public with an unsolicited offer. A target’s employees and clients will also learn about the effort, perhaps making them more susceptible to competitors, Thompson said. So it is important for an aggressor to communicate stability and outline a retention plan for a target’s staff.

“I think it’s a pretty tough row to hoe,” Thompson said.

Public overtures to a target’s shareholders, employees and clients could also shape broader perceptions of an aggressive institution, industry observers said.

“Reputation means a lot,” said Bob Wray, managing director at Capital Corporation in Prairie Village, Kan.

“In the Midwest, I think it would be very detrimental” to an aggressor’s future M&A prospects, which could explain a dearth of hostile takeovers, Wray said, adding that he would typically steer his clients clear of such efforts. “I think it could have a negative impact with certain targets in a nonhostile” situation.

Banks should also

SunTrust Banks in Atlanta famously

Hanmi briefly tried to interfere with BBCN Bancorp’s 2016 acquisition of Wilshire Financial.

An unsolicited bid sometimes spurs a target to sell to another institution. Dime Bancorp in New York agreed to sell itself to Washington Mutual in 2001 after North Fork Bancorp in Melville, N.Y., initiated a

“In certain circumstances, it compels the target to take action one way or the other,” Wray said.

First Citizens can take some comfort knowing that some efforts succeed.

Cathay General Bancorp

Banks that successfully buy the targeted institution still have considerable work to do to maintain a positive reputation with future sellers, Plath said. First Citizens, for instance, would be well served to retain as many KS Bancorp employees and branches as possible, he said.

Using a “scorched-earth” strategy can stigmatize a bank, Plath said.