Executives at Dacotah Bank in Aberdeen, S.D., wanted a powerful incentive for employees to live healthier lives, so they started offering a discount on the employee share of insurance premiums in 2018 as part of a wellness program.

To get the discount, which is $600 a year, employees of the bank had to get an annual physical, go for two dental checkups and attend training in areas such as stress management, among other steps. Nearly three-quarters of the bank's 394 eligible employees earned the discount last year and Dacotah's year-over-year spending on health care claims was down 2.5% as of mid-2019.

Though not enough to cover the added expense of the premium discounts, the drop is a sign of progress on the overall health of employees, said Joe Senger, the president and chief executive of the $2.6 billion-asset bank.

Still, he is reluctant to conclude that the wellness initiative is the reason health care claims fell.

"I can't say that there's a direct correlation," Senger said.

That is the mantra for many banks that offer wellness programs.

The programs are meant to encourage employees to exercise, eat healthier foods and better manage the risks of chronic illnesses like heart disease and diabetes. The thinking is that if employees embrace the effort, health care costs will drop.

But whether the actual return on investment can be measured is up for debate, said Tracie Sponenberg, who serves on an expert panel for the Society of Human Resource Management in Alexandria, Va.

For wellness to be effective, she said, companies are better off starting with a goal of helping employees, not necessarily aiming for a direct return.

"I think we're still trying to get our arms around what exactly do we measure?" said Sponenberg, who is also the senior vice president of human resources for the Granite Group, a wholesaler of plumbing and heating supplies in Concord, N.H. "Is it important to measure or is it the right thing to do?"

Other factors can affect health care costs, frustrating efforts to assess the impact of a wellness program.

At Dacotah, the bank's workforce is getting younger as an influx of new employees replaces retirees, Senger said. And an expensive medical claim or two could easily drive up costs for the bank, which is self-insured and spends about $4.5 million a year on health care. Employees contribute to their health care coverage; Dacotah absorbed the cost of the discount.

Senger said he expects a stronger wellness program to make a difference. "We're hoping that it's going to give us a long-term trend of lower costs," he said.

Other banks on the 2019 list of Best Banks to Work For also have seen progress in cutting health care spending — or at least in slowing its growth.

Like Dacotah, they hesitate to draw conclusions about cause and effect. But they are measuring progress on wellness in other ways, such as participation, overall health and, in one case, use of sick days.

And they point to the intangible benefits of wellness programs, which can encompass psychological and financial health, in addition to physical health. Employees may be more engaged as a result and more likely to make an extra effort at work.

"We think it contributes to creating this workplace that's very attractive, which we think creates good results financially," said Douglas Williams, president and CEO of the $2.9 billion-asset Atlantic Capital Bank in Atlanta, which has roughly 200 employees.

Wellness may not be the most important feature of a competitive benefits package, he added. But "it's more than icing on the cake. It's one of the foundational elements of building an attractive culture."

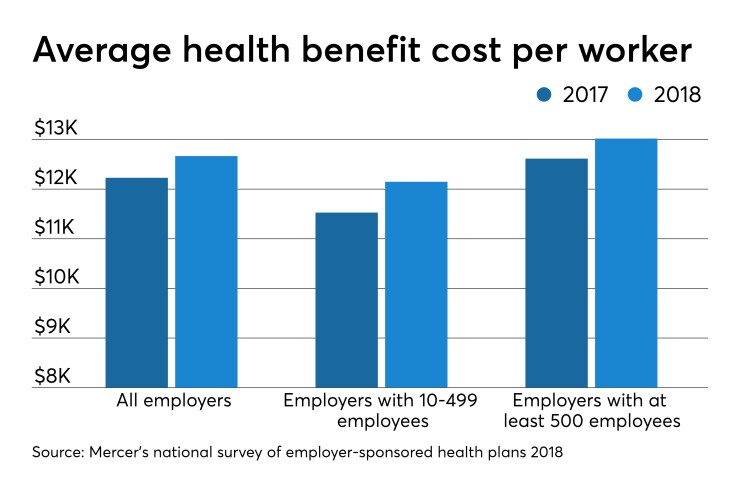

The programs have become more robust over the years, Williams said. They are a way to deliver value to employees as they are asked to pay more for their own health care.

"It's sort of part of the benefits arms race, if you will," Williams said.

The wellness program was strengthened in 2018 in an overhaul of Atlantic Capital's culture, said Annette Rollins, the bank's chief human resources officer. The goal was to help more employees and increase engagement, she said.

Now employees who have health insurance through the bank can earn premium discounts of about 30%, Rollins said. But there are also rewards for those whose insurance comes from other sources. They can earn points redeemable for merchandise and gift cards.

"We wanted to be inclusive of our entire work population," Rollins said.

The changes are less than a year old, so it is too early to measure the results. But feedback has been positive, turnover is down and the bank has had some success encouraging employees to switch to lower-cost generic prescriptions, Rollins said. She declined to share turnover statistics, but said generic prescriptions now account for 97% of the bank's total.

Banks recognize that the goal with any wellness program is for employees to adopt healthier habits in their everyday lives, not just sit through sessions on healthy cooking or compete to take the most steps in a week.

The results of biometric screens can offer a glimpse into whether that is happening, several bank executives said. The screens are designed to gauge employee health by measuring things like blood pressure, glucose and cholesterol. Employees can use what they learn to adopt healthier lifestyles.

Individual data is confidential, and the aggregate results can be skewed by turnover. But screening offers opportunities for banks to gather data and try to control costs.

More Best Banks to Work For coverage:

Best Banks to Work For Stearns Bank's message to employees: 'Prioritize yourself' To reach the goal line, Citizen States focuses on 10 yards at a time A small change to Pinnacle's wellness program went a long way

Using what it has learned from biometrics, Peoples State Bank in Wausau, Wis., is planning to offer individualized coaching to employees prone to chronic illnesses.

"That tends to be where your plan spends all its money, on those high-risk individuals," said Donna Staples, human resources director for the $893 million-asset bank.

Peoples State has contracted with an outside provider to start offering the coaching in 2020 to employees the bank believes could benefit from it.

Another idea it might implement in 2020 is to expand insurance coverage for preventive medical visits, Staples said. The bank's plan covers one per year. But executives are weighing whether it is worth the cost of covering more visits for people who could benefit from regularly tracking risk factors like their cholesterol or blood pressure.

One goal is to lower costs overall. But if possible within privacy rules, the bank also would like to measure improvement healthwise, perhaps by tracking whether its at-risk population declines or registers better biometric scores as a group, Staples said.

Executives at Apollo Bank in Miami are hoping they may learn something from a new policy for sick days.

This year, for the first time, Apollo is allowing employees to carry over unused sick days from one year to the next, said Melissa Pineda, director of human resources at the $703 million-asset bank.

"That will allow us to understand the effectiveness of our wellness program and see how many don't use all their sick-time benefits and roll it over," she said.

Under the old policy, many employees were taking sick days in November and December, suggesting they may have wanted to use them before they lost them, Pineda said.

The absences ate into productivity and efficiency, she said. The new policy is "a really big morale boost and cultural enhancement."