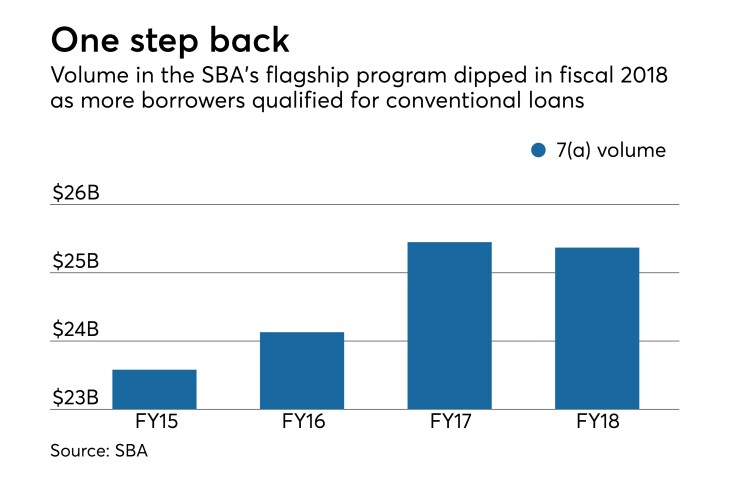

The Small Business Administration’s flagship program just missed hitting another record high.

Volume at the agency's 7(a) program fell by 0.3% in fiscal 2018, which ended on Sept. 30, to $25.4 billion. Though a nominal decline, it is noteworthy given several years of accelerated lending that had on multiple occasions forced lawmakers to authorize mid-year increases to the SBA's authorization cap.

Bankers and other industry observers noted that the final tally remained high and that the reasons for the decline can actually be viewed in a positive light.

The decline in guarantee volume was largely a function of the strong economy, which has allowed more banks to direct clients to conventional loans, said Bill Manger, associate administrator for the SBA's Office of Capital Access. It could also show more discipline on the part of lenders, industry observers said.

“Historically speaking, this past year was still strong,” said Jim Fliss, national SBA manager for the $138 billion-asset KeyCorp in Cleveland, characterizing the dip as little more than "a rounding error.”

Bankers said they still view the SBA's loan programs as an important tool even though more borrowers are qualifying for traditional credit. And the relationship between bankers and the agency seems to be steadily improving.

“I have seen nothing but an increase in professionalism from the agency from then until today," said Chip Mahan, chairman and CEO of the $3.5 billion-asset Live Oak Bancshares in Wilmington, N.C. Mahan had been associated with SBA lending since the late 1980s.

Live Oak was the nation's most prolific 7(a) lender in fiscal 2018, originating nearly $1.3 billion in loans. It edged out perennial leader Wells Fargo, which came in second with $1.2 billion in production.

The ranking reflects Live Oak's emphasis on personnel, expertise and technology, said Huntley Garriott,

Wells, for its part, remains committed to the program.

“While we continue to see shifts in lending activity across the industry, Wells Fargo is proud of its longstanding history in SBA lending — as a national SBA Preferred Lender that extended more than $1 billion in SBA loans in the federal fiscal year 2018 to businesses of all types and sizes, including smaller and newer businesses,” said Lindsay Bosek, a company spokeswoman.

Volume at credit unions fell sharply, declining by 9.5% in fiscal 2018. The number of 7(a) loans originated decreased by 12%. No credit unions placed among the program's top 100 lenders; only five nonbank lenders made that list.

Credit quality remained stellar in the last fiscal year, with charge-offs totaling just 0.23% at the end of March, according to the most recent SBA data. That compares with 2.02% in fiscal 2015.

Still, bankers are divided on how long the good times will last.

“The regulatory environment is improving, the economy is improving, I expect SBA will benefit as well,” said Kevin Ferryman, director of SBA lending at the $930 million-asset Patriot National Bancorp in Stamford, Conn.

Mahan was skeptical, describing a stage in the cycle where banks are eager to make loans, increasing the likelihood of risk-taking.

“It’s the time in the cycle that I call la-la land,” Mahan said. “A lot of banks are highly liquid. There’s plenty of capital out there. Nobody’s even talking about credit losses.”

Changes are afoot at the SBA, and it is unclear how they will impact fiscal 2019.

President Trump in June

The SBA appears set to narrow the scope of its fee waiver for smaller loans. Under its plan, announced in August, most small-dollar borrowers will pay a 2% guarantee fee, unless their loans originated from rural areas or a region designated by SBA as a historically underutilized business zone. Loans from those designated areas would pay a roughly 0.67% fee.

Fee relief for certain types of loans to veteran-owned businesses is mandated by law.

The added revenue from the fees would help the SBA to keep operating 7(a) at a zero subsidy, meaning that credit costs are paid by user fees, rather than a congressional appropriation, Manger said.

Bankers are paying close attention to how the SBA handles fee waivers.

“I don’t know that it’s going to be catastrophic, but it is an additional" cost, Fliss said. "The jury’s still out.”

Some changes, particularly to rules implemented in the aftermath of the financial crisis, make sense, bankers said.

“If you step back and you think as a taxpayer what has happened over the last 10 years, we had the worst recession we’ve seen since the 1930s, and we changed some rules,” Mahan said. "It was the right thing to do. Now that we’re enjoying one of the finest economic recoveries in the history of this country, we're changing the rules back to something more traditional. I think that’s OK."

The agency has also

Despite the proposed changes, more lenders are adding scale in SBA lending.

The $1.3 billion-asset SunWest Bank in Irvine, Calif.,

The $1.3 billion-asset River Valley Bancorp in Wausau, Wis., announced plans in August to form a national SBA lending division, a move that followed a long search for a lending team, said CEO Todd Nagel. River Valley wants to run a “boutique” operation to complement its growing equipment finance and insurance lines.

Patriot National spent months drafting a set of policies, procedures and compliance guidelines, Ferryman said.

“We’ve built a really strong foundation," Ferryman said. "Now, were starting to hit our stride."