For half a decade, big banks and retailers have been quarreling about the effects of government-imposed price caps on U.S. debit card fees.

The banks contend that merchants have pocketed

Retailers say

What is lost in this high-stakes tit-for-tat, which is being

Yet there is mounting evidence that as a result of the five-year-old debit card rules — or more precisely, as a result of how the banking industry responded to the rules — Americans are spending more money on their credit cards.

Between 2012 and 2015, the number of U.S. credit card transactions grew slightly faster than the number of debit card transactions, according to Federal Reserve data. Those numbers represent a huge turnaround from the previous decade, when debit card use was growing by leaps and bounds.

The price cap is surely not the only factor in the shift, but experts say that it had a significant impact. “It’s an important part of the picture,” said Nick Clements, a former credit card industry executive.

Many Americans who lean heavily on reward-laden credit cards are likely benefiting in today’s landscape. But the shift toward plastic carries risks for other consumers, who may incur finance charges. The trend may also be having a negative influence on some consumers’ saving habits.

Rewards growth fuels credit card spending

The Fed’s debit card fee ceiling was implemented in response to 2010 legislation that was sponsored by Sen. Richard Durbin, D-Ill.

Since the Durbin amendment took effect, banks that are subject to it

Meanwhile, the fees that banks get paid for credit card purchases were unaffected by the Durbin amendment. Today those charges are often

Even before Congress passed the Durbin amendment, banks had a financial incentive to encourage the use of credit cards, because of the interest income and penalty fees they collect from consumers. But the math became more compelling once the debit card price ceiling took effect.

“If someone has a choice between push steak and beef stew, they make more money on steak, so they’ll push the steak,” said Mallory Duncan, senior vice president at the National Retail Federation.

Referring to the banking industry, he said, “If they can make monopolistic fees on credit cards, they’re going to push credit cards.”

The U.S. credit card industry is heavily concentrated — JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup, American Express, Capital One Financial and Discover Financial Services have roughly 70% of the total market share. Over the last five years, the big six issuers have sought to attract credit card spending by continually sweetening the cash and travel-based rewards they offer to their customers.

In 2013, Capital One launched the Quicksilver card, which offered 1.5% cash back on every purchase. The following year, Citi rolled out its Double Cash card, which further upped the ante. In 2016, Chase announced Sapphire Reserve, which offered new cardholders points worth $1,500 if they spent $4,000 in the first three months.

“There’s been an arms race between issuers,” said Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate.com.

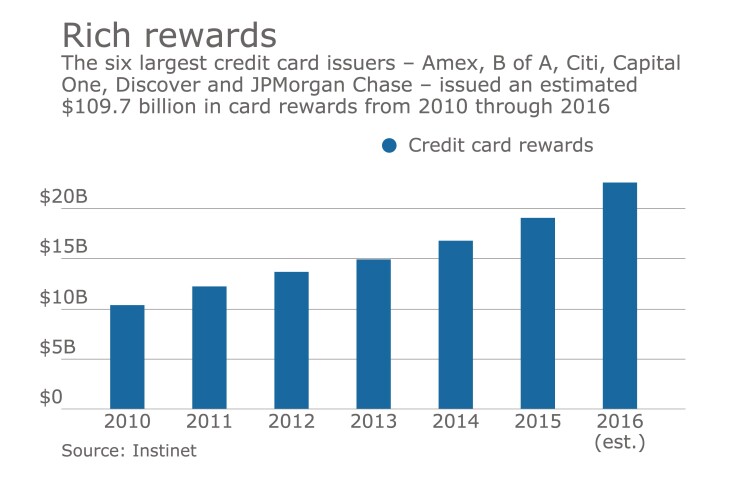

In 2011, the big six issuers sent $12.2 billion to consumers in the form of credit card rewards, according to a recent research note by analysts at Nomura Instinet. By last year, that figure had risen to $22.6 billion.

“Attractive credit card rewards … have fueled credit card spending volumes,” the analysts wrote.

Mixed outcomes for U.S. consumers

The most comprehensive report on Americans’ payment habits is published by the Fed once every three years. It is based on data reported by a sample of depository institutions.

During the 2000s, before the arrival of the debit card fee cap, consumers’ use of debit cards grew rapidly, according to the Fed data. Between 2003 and 2006, U.S. debit card transactions increased by 74.4%. Between 2006 and 2009, those payments grew by 52.6%.

Meanwhile, U.S. credit card transactions grew by just 14.2% between 2003 and 2006, and they actually declined by 3.2% during the next three-year period.

A number of factors are at play here. The U.S. debit card market was still fairly small in the early 2000s, which made it easier to achieve impressive growth rates. And during the Great Recession, many consumers had their credit lines cut, which undoubtedly had a significant impact on credit card spending in 2009.

Still, the spending patterns from the 2000s were a reflection of the banking industry’s substantial efforts to market debit cards at that time. Part of the industry’s motivation was to reduce consumers’ use of checks, which are costly to process. Hefty interchange fees on debit cards were another factor.

The Durbin amendment took effect in October 2011. Between 2012 and 2015, credit card transactions grew by 26.1%, slightly outpacing debit card transactions, which rose by 23.0%, according to the Fed data.

During the same three-year period, spending on credit cards rose by $610 billion, compared with a $460 billion increase in debit card spending, the Fed found.

This turnaround from the previous decade’s spending trends happened despite the fact that many consumers, chastened by the financial crisis,

To be sure, the share of cardholders who use credit cards in low-risk ways has been growing.

In the third quarter of 2016, 29.2% of U.S. credit-card holders paid off their entire balance each month, according to the American Bankers Association. That figure was just 19.5% in the third quarter of 2008.

For savvy shoppers, leaning heavily on a credit card that offers generous rewards can yield substantial savings. “If you really use it to your advantage, there’s a lot of money that you can squeeze out of it,” said Brian Riley, director of the credit advisory service at Mercator Advisory Group.

But for credit-card holders who pay interest charges each month, the recent shift in spending patterns is more worrisome. Consumers

In the fourth quarter of 2016, Americans had access to $2.57 trillion in available credit on their cards, an increase of more than $470 billion from four years earlier, according to

Even for consumers who pay off their entire bill each month, an increased reliance on credit cards may have negative repercussions.

In any event, the U.S. personal savings rate is currently 5.4%, which is higher than it was during the credit bubble of the mid-2000s, but well below its levels in the 1960s, '70s and '80s.

Spending patterns are absent from the policy debate

In Washington, the Durbin amendment has long been viewed as a zero-sum game between banks and retailers: Congress can either satisfy merchants by keeping the price ceiling in place, or it can fulfill the wishes of banks by repealing the five-year-old regulation.

Lobbyists on both sides of the debate have not shown much interest in studying how the price ceiling has impacted consumers’ spending habits. After all, banks and retailers both make a lot of money from credit cards, and they do not have a lot to gain by casting their increased use in a negative light.

The Electronic Payments Coalition, which represents banks in the debate over the Durbin amendment, did not provide comment prior to deadline.

Duncan at the National Retail Federation acknowledged that some of the recent growth in the use of credit cards may be attributable to the Durbin amendment, but he also pointed to other factors, and said that credit card use was already on the rise prior to October 2011.

He also took issue with the notion that credit cards cause consumers to spend more. He noted that consumers typically use credit cards to buy bigger items but added, “That doesn’t mean that the credit card causes the higher purchase.”