WASHINGTON — When the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. broke a decadelong freeze in March 2020 in approving new industrial loan companies, fintech advocates celebrated what they hoped would be an enduring thaw.

But a year and a half later, the political environment is not in ILCs' favor. Democratic appointees hold a 3-1 majority on the FDIC board, giving them enough votes to reject any application that they oppose.

“I expect the Democrats on the board to take a hard look at any charter application that attempts to mix banking and commerce,” said Todd Phillips, director of financial regulation at the Center for American Progress and a former FDIC attorney.

The ILC, also known as the industrial bank, remains a

While the prudential regulators appointed by the Trump administration were generally eager to open their charters to fintechs, the Biden administration has signaled a more cautious approach.

“It's been clear that there are many people in the industry, academia and policymaking circles for some time that have raised very significant concerns about ILCs and industrial banks,” said Dennis Kelleher, president and CEO of Better Markets.

He added those concerns “are shared by the Biden administration and the professional regulators they have.”

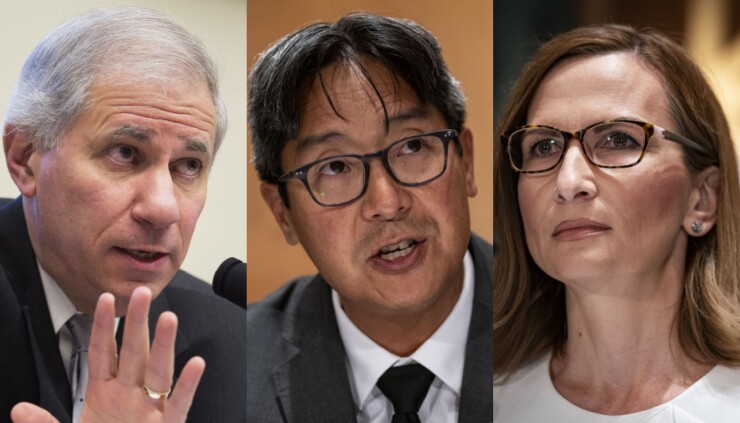

The FDIC is led by Chair Jelena McWilliams, a Trump appointee, whose term is set to expire in mid-2023. But the agency’s five-member board — which must vote to approve any new industrial bank application — is now stacked with three Democrat-appointed votes: Michael Hsu, acting comptroller of the currency; Dave Uejio, acting director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau; and Martin Gruenberg, an FDIC director and former agency chair. (The fifth seat is unfilled.)

McWilliams had signaled the board might be more open to ILCs during the Trump administration. In March 2020, the agency approved charters for the payments firm Square and Nelnet, a student loan servicer, the first ILC approvals since 2008.

But the current makeup — even with two acting officials serving on the board — could mean the thaw is short-lived. Gruenberg notably opposed Square's application, and no firm was able to open a new industrial bank when he led the FDIC between 2011 and 2018.

The ILC charter has long been controversial. Bankers and other critics say it gives nontraditional bank owners a legal loophole from the Bank Holding Company Act, subjecting them to lighter regulation than more mainstream financial institutions and allowing commercial firms to enter the banking system.

Some observers say the addition of Hsu, who took the helm of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency in May, to the FDIC board is particularly noteworthy. He was formerly a senior official at the Federal Reserve, which historically opposed the ILC charter because it skirted bank holding company supervision.

“Michael Hsu is a dyed-in-the-wool Fed guy, and the industrial loan loophole was intended to undermine the Fed's authority under the Bank Holding Company Act,” said Todd H. Baker, senior fellow at the Richman Center for Business, Law and Public Policy at Columbia University. “So the Fed as an institution has never felt positive towards the ILC charter.”

But others say that it would be a mistake for fintechs to rule out the ILC as a charter option this early into the Biden administration.

“It's always been hard to get an ILC; that itself is not news,” said Michele Alt, a partner at Klaros Group and a former lawyer at the OCC.

“So what’s the impact of the Biden administration?” Alt said. “I would say we don’t know. It’s not at all clear to me that the current state of play has anything to do with the administration’s views on bank regulation, or specifically ILCs, because the Biden administration hasn’t said anything.”

Yet the signs point to Biden administration officials being more cautious, in general, about approving bank charters for fintech firms. Hsu has said the OCC is conducting a review of fintech chartering decisions made by Trump-era comptrollers. He has stressed the need to balance competing policy priorities when it comes to allowing new entrants into the banking system.

In written testimony submitted to Congress in May, Hsu acknowledged that “some are concerned that providing charters to fintechs will convey the benefits of banking without its responsibilities.” But he also noted that “others are concerned that refusing to charter fintechs will encourage growth of another shadow banking system outside the reach of regulators.

“I share both of these concerns,” Hsu concluded.

Still, Hsu and other Democrats have also focused on promoting financial inclusion, which some analysts say provides an opening for a financial technology firm to responsibly serve those populations. And Gruenberg’s opposition to ILCs has not been monolithic; he did not object to Nelnet's industrial bank charter.

“If you look at the most recent statements made by the acting comptroller in congressional hearings, one of the things he talked about was really reducing inequality in banking,” said Peter Dugas, executive director at Capco.

“One of the things we’ve seen Democrats discuss quite extensively is fintech companies and fintech providers being able to serve as a mechanism in which they can address low-income populations where the banking system may not be able to get access to provide the services which would address any equality in the banking system,” Dugas said.

Any additional slowdown in rulings on ILC applications will likely cause legal headaches for any fintech in the process of seeking an industrial bank.

There are currently five pending applications for an ILC charter: Thrivent, Rakuten Bank America, Edward Jones, General Motors Financial Co. and Great America Bank. A sixth applicant, Brex,

“Everyone's in this deeply unfair situation where they're spending millions of dollars based on legal advice that says they should be able to get some charter, and yet administratively, because of the Michael Hsu situation and a lack of guidance from Congress, there’s no assurance that they will be able to get one,” said Baker.

The OCC and FDIC declined to comment for this story. An OCC spokesperson said that “as an FDIC board member, it would be inappropriate to comment on potential board deliberations or decisions.”

But analysts emphasize that all is not lost for ILC aspirants.

“This could be a good time to do a lot of the heavy lifting that goes into assembling a business plan and an application in order to be poised to file when those clouds lift,” said Alt.

Baker agreed, noting that the administration could nominate a permanent head of the OCC who is more favorable to ILCs.

“The smart players who have a long-term view are spending money prudently now so that if the logjam breaks, they'll be in the best position to get a charter issued should the confirmed comptroller, whoever he or she may be, be in favor of the ILC,” Baker said. “If you've got a long-term view and you're willing to take some risk, building up your structure so you're in the best position is probably a smart thing.”