Albert Amini and the team working on Discovery Business Bancorp in Chandler, Ariz., see a need for a local bank to serve area entrepreneurs and small businesses.

While initial approval from the Arizona Department of Financial Institutions is required before organizers can start raising capital, the de novo effort already has a niche in mind. In addition to traditional banking services, Amini said he envisions Discovery offering educational resources to small-business owners.

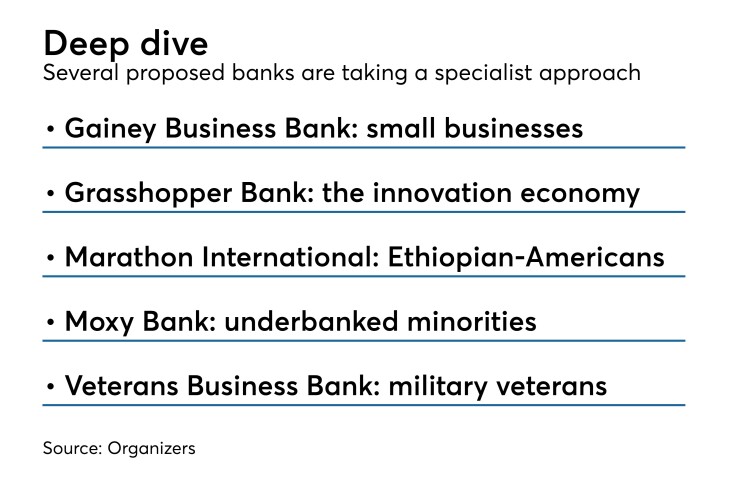

Several other groups are also identifying specialization for their de novos. Another Arizona group hopes to open banks focused on military veterans. Moxy Bank, a proposed minority-owned bank in Washington, would focus on low- and moderate-income clients. And Grasshopper Bank in New York intends to serve the innovation economy.

Before the financial crisis, many de novos were built to bulk up and eventually sell, said Greyson Tuck, an investment banking adviser at Gerrish Smith Tuck. That model is changing, Tuck said. Becoming well known in a niche could be a way for new banks to add value and stand out in a competitive market, industry observers said.

“I have long thought it a good idea for regulators to be more receptive to banks that appeal to relatively narrow niches,” said Ray Grace, North Carolina’s banking commissioner. “Provided that the market analysis is sound and it appears to be a model that is sustainable over the long term, niche banks are a good idea.”

The key for bank organizers is finding niches where they can find experienced staff and avoid taking on too much risk.

A group in Arizona is in the preliminary stages of forming a bank to serve military veterans. Ernie Garfield, owner of Interstate Bank Developers, a firm that specializes in forming de novos, is leading an effort to create Veterans Business Bank, which has not yet applied for a charter or for initial approval from the state. He hopes to open 15 to 20 community banks to serve veterans in five years.

"With the U.S. economy booming, the timing is perfect to open ownership and governance of community banks to those who have served the nation and their respective communities,” Garfield said. “Consolidation in the banking industry has created a barrier for veterans who want to start or grow their own businesses.”

Organizers of Moxy Bank plan to reach underbanked groups by offering traditional services and a financial literacy program.

To be sure, a handful of groups have proposed more traditional approaches. But having expertise in a specific areas could help strengthen a bank’s ties to customers, said Paul Schaus, president and CEO of CCG Catalyst Consulting Group.

Technology has made it easier for community banks to reach particular niches, Schaus added.

“Because of technology, 'community' has to be redefined, and it is no longer geographically based because our clients are not defined to a particular map,” Schaus said. “To be successful ... you have to be focused and have subject matter experts in a particular niche. That way you attract people to your bank by creating a common bond.”

Studio Bank in Nashville, which opened in June, is blending the specialist and generalist approaches, said chairman, CEO and President Aaron Dorn. The bank has hired bankers with specific expertise in areas such as health care, nonprofits and the music industry.

“When you combine all of those together, it creates a broad ability to serve different industries,” Dorn said. “I would say our approach is the best of both worlds of a niche bank and also a general community bank.”

It is beneficial to have experts who know each respective industry, Dorn said. Studio’s music industry specialist, for instance, once was a songwriter.

“There are specific products and service arrangements that we have to have for the music and entertainment space that we don’t necessarily have to have for another line of business,” Dorn said.

Raising $46 million in initial capital will help Studio Bank execute its strategy, Dorn said.

Honing in on a particular niche has proven to be a profitable move for Bank of Bird-in-Hand in Pennsylvania, the first de novo to open after the financial crisis. The bank, which opened in late 2013 to serve the Amish community, recently surpassed $300 million in assets. The bank earned $2.1 million last year, easily surpassing the $693,000 it made in 2016.

The concept and business plan was well received by regulators during the organizing process, said Lori Maley, Bank of Bird-in-Hand's president and CEO.

“It really is a success story,” Maley said.