Data aggregators and fintechs have taken heat in recent days on the subject of cybersecurity — and they say the criticism is unfair.

The debate got rolling last week when Kenneth Blanco, the director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network,

“Anytime information is exchanged between parties, there is potential risk that the information can be compromised, and that risk is compounded as more parties, such as aggregators and fintechs, are added into the mix,” Gary McAlum, senior vice president and chief security officer at USAA, said later in response to questions from American Banker.

Yet, synthetic identity fraud has been around for a long time. Fraudsters combine pieces of stolen identity information with made-up details to create a digital identity that looks real and might pass certain verification checks, but does not match any one person. The fraudsters often conduct legitimate transactions on the synthetic identity's account for some time, to establish good standing. Then when they feel the time is right, they will "bust out" — in other words, make some major purchases or take out a loan that will never be repaid.

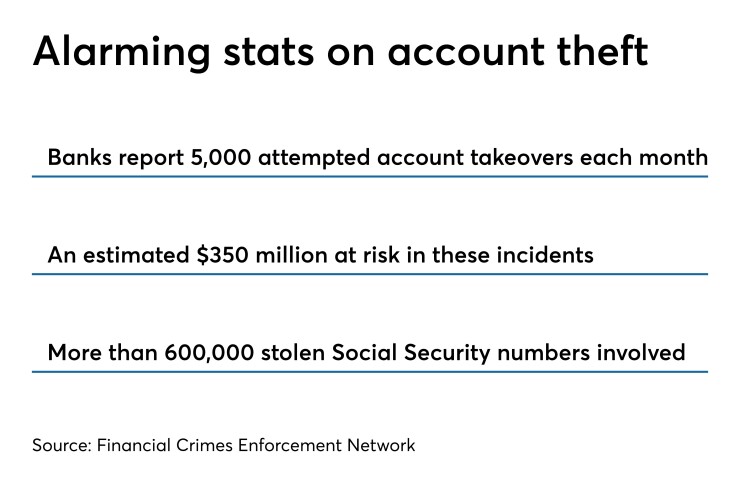

To what extent are data aggregators exacerbating these problems? Blanco did not cite any evidence supporting the assertion that aggregators are facilitating this kind of crime. Fincen and the Financial Services Information Sharing and Analysis Center, the organization to which banks report fraud incidents, did not respond to requests for interviews. Neither did several large-bank security executives.

Executives at data aggregators and fintechs interviewed for this article agreed that fraud, especially synthetic identity fraud, is a problem. But they said they were unaware of aggregators or fintechs being specially targeted. Moreover, they said they flag and block fraudulent transactions that banks would be unable to see on their own.

Kareem Saleh, executive vice president at ZestFinance, an AI software company focused on the credit market, said synthetic fraud has been a real problem in the industry that has plagued everyone, even the most prestigious financial institutions.

“They’ll steal an identity, usually of a young person with no credit history,” he said. “And then they’ll do a flurry of small-dollar transactions that they pay for to help the fake person build a credit history. Then they increase the credit lines and go out and do a big bust-out. We’ve seen some very determined fraudsters steal the identity of a thin-file or no-file person, assume that identity for a period of six to nine months, behave well from a credit perspective, then go out and commit major fraud with the increased ability to borrow money.”

But Saleh said he has not seen signs that cybercriminals are taking advantage of aggregators and fintechs to do this.

“This is the first I’ve heard of that,” he said.

Nate Caldwell, product general manager at MX Technologies, a data aggregator and data insights provider, acknowledged that without strong communication and transparent access, aggregator traffic on a bank’s servers gets lumped in with malicious traffic, making fraudsters harder to identify.

“It’s important to tie together security and data sharing, as this hasn’t always been the case in our industry,” he said.

But Caldwell also argued that despite the risks, by monitoring traffic and applying their own fraud detection technology, aggregators can make digital banking more secure.

“Through increased partnerships with financial institutions, aggregators can provide insight across financial institutions, which can be valuable to identify macroscopic trends and to improve overall security,” Caldwell said.

Steve Boms, executive director of the Financial Data and Technology Association - North America, which has data aggregators among its members, said that in some cases data aggregators already help banks detect fraud.

“The aggregators will see fraudulent credentials out in the ecosystem being used as tests, to see whether they’re able to log in or not,” Boms said. “And they’ll alert financial institutions to those credentials being out there, so the accounts can be investigated and if necessary, those credentials suspended.”

At least one data aggregator is encouraging the banks it works with to require customers to use multifactor authentication, typically in the form of a one-time passcode to the customer’s phone. If the bank does not require it, the aggregator will force the customer to use its own multifactor authentication.

Of course, it is in the data aggregators’ best interest to say they are not introducing risk into the system.

“If you ask a fox the merits of having foxes guard henhouses, they will always say, what a great idea,” said Richard Parry, principal at Parry Advisory and former risk management executive at JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Visa. “The data aggregators have poured millions into data aggregation, they have perfected the art of interrogating data, and in the process of doing that they've sorted it. So the process of aggregating it, and then their total failure to protect it from breach, is what creates the vulnerability because the crooks are breaching and acquiring data that they don't even have to aggregate anymore.”

When he refers to data aggregators, Parry said he is referring to Facebook and all the major credit bureaus as well as aggregators like Plaid, Envestnet Yodlee and Finicity. The problem of account takeover fraud and synthetic identity is systemic, he said.

“Our national system of identity is a data-consistency model, which doesn't mean you are who you say you are,” Parry said. “It means you are the person who's assembled enough data to look good.”

Parry also said multifactor authentication, even with biometrics, is pointless if a company does not know who it is enrolling.

“We’re doing more and more of that enrollment online and over the phone with mobile devices,” he said. “So if I enroll my face, fingerprint and retina, but it's not checked against anybody else's face, fingerprint and retina and is only checked against the data I send in with it, there’s no way to know” if it is a synthetic identity.

Biometrics systems are not federated, so someone can register their biometric characteristics in different places without anyone ever cross-checking.

Tokenization isn’t an answer either, according to Parry.

“There's no point in putting a gold-standard lock on the door if you don't know definitively who you're giving the gold-standard key to and checking it every time you give access,” he said. “I believe in tokenization, but not without making sure you know who you gave it to.”