A large number of credit unions are buying into the adage bigger is better.

Credit union mergers typically involve smaller deals, often with acquired institutions having less than $100 million in assets.

Since March, however, there have been three deals in which the credit union being acquired had more than $300 million in assets. And a New York investment banker said he is working on a fourth deal — with even more possibly on the way.

Those deals threaten to create bigger, and more formidable, credit unions to compete against banks.

“That’s noteworthy,” Peter Duffy, a managing director at Sandler O’Neill, said of the uptick in bigger credit union deals. "We're in dialogue with a number of institutions and they're above $300 million in assets."

The same factors that are driving banks to sell — rising technology costs, burdensome regulation and a need for scale — are influencing the decisions of credit union executives. Any effort to remove credit unions' tax-exempt status could spur more merger discussions.

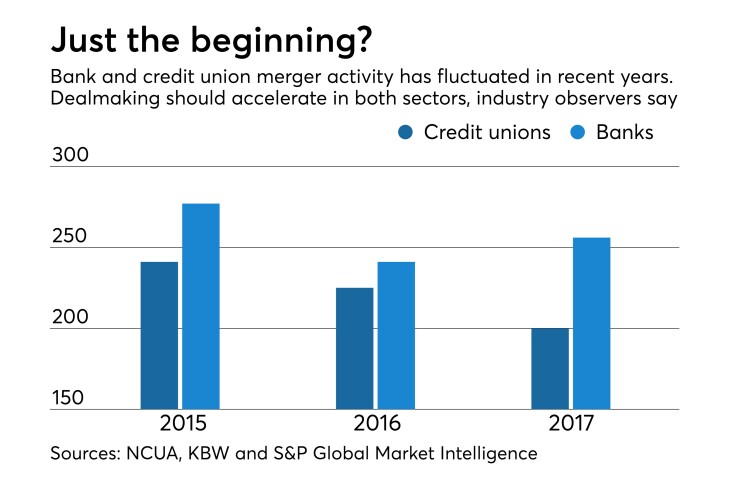

Nearly 670 credit union mergers took place between 2015 and 2017. That volume wasn't too far off from the 774 bank deals announced over the same time period.

Credit unions “are looking for a safe haven,” said Richard Garabedian, a lawyer at Hunton Andrews Kurth who frequently works with credit unions. “With all the regulatory burden and the need to have all the technology that other bigger institutions have, they’re going to feel the need to find a merger partner.”

Banking advocates aren’t especially sympathetic.

“The larger ones are the ones that compete the most vigorously in commercial lending,” said Chris Cole, senior regulatory counsel at the Independent Community Bankers of America. “They’re getting larger and grabbing market share.”

The American Bankers Association is also keeping an eye on the situation, said Brittany Kleinpaste, the group's vice president of economic policy and research.

Larger credit unions "are the ones causing different levels of competition,” Kleinpaste said. “’It's not cannibalizing just banks. They’re pushing smaller credit unions out of certain areas.”

All three credit unions that announced big deals since March have significant member business lending portfolios.

The $543 million-asset Vibe Credit Union in Novi, Mich., which

The $1.6 billion-asset NuVision Credit Union in Huntington Beach, Calif., has $203 million in member business loans. It agreed in March

Several factors could deter large credit union combinations, including a reluctance by many boards to trade away their institutions’ independence — as well as their own positions — to create a bigger entity, Garabedian said.

“It’s always harder with credit unions because they don’t have that impetus of shareholder fiduciary duty,” Garabedian said. “They have a fiduciary duty to the members, but that’s not the same thing. It’s harder to get their boards to sign off on a merger.”

Garabedian recalled a deal he was working on in California where the other party ended up walking away from a proposed combination.

"The other institution — not my client — didn’t quite get the benefits of the combined entity,” Garabedian said. “You’ll see [the trend] scale up somewhat, but I don’t know how far up the food chain it will go.”

Duffy, who acknowledged the potential reluctance of credit union directors, said powerful reasons still exist to force them to confront the industry's future.

“The balance sheet of banks and credit unions has commoditized, so few institutions with assets less than $1 billion have any pricing power,” Duffy said. “The operating environment is not getting better, consumers aren’t getting less demanding, the regulator is not less demanding, and the need to pay good people hasn’t lessened."