WASHINGTON — Some banks and consumer advocacy groups support anti-redlining rule reform, defying banking trade groups' opposition while arguing the changes are needed to promote community lending and won't overburden smaller banks.

A

They say the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency exceeded their statutory authority with the new regulations, which expand the scope of where regulators evaluate banks lending. Under current rules, banks are assessed on how well they lend near their branch locations. The new CRA would extend such assessment areas beyond those sites and into areas where banks do significant business.

The rules — which apply to firms with more than $2 billion in assets — encourage banks to lend capital to the communities where they take deposits from consumers. The rules adjust the way banks are graded for CRA ratings, and regulators will take those ratings into account when institutions apply to open new branches or make an acquisition or merger.

The strongest public opposition to the ABA's lawsuit emerged when Beneficial State Bank, based in Oakland, California, joined civil-rights groups in

"[The new rule is] not, frankly, a huge stretch," said Randell Leach, CEO of Beneficial State Bank, in an interview. "When the lawsuit came out trying to stop it, that just didn't sit right… It looked like the large banks that sort of have the most influence were basically throwing their weight around to undermine something that was actually going to be good for communities and good for a population of banks as well."

Leach — like many advocates of the rule — has criticized the lawsuit because he says it perpetuates the banking industry's history of discrimination. Leach said the big bank trade groups are fighting measures intended to right the wrongs of the past.

"[CRA] is saying you're doing great things for the economy, but you are leaving populations behind, communities behind," he said. "And with great power comes great responsibility, so step up and do some of these basic things."

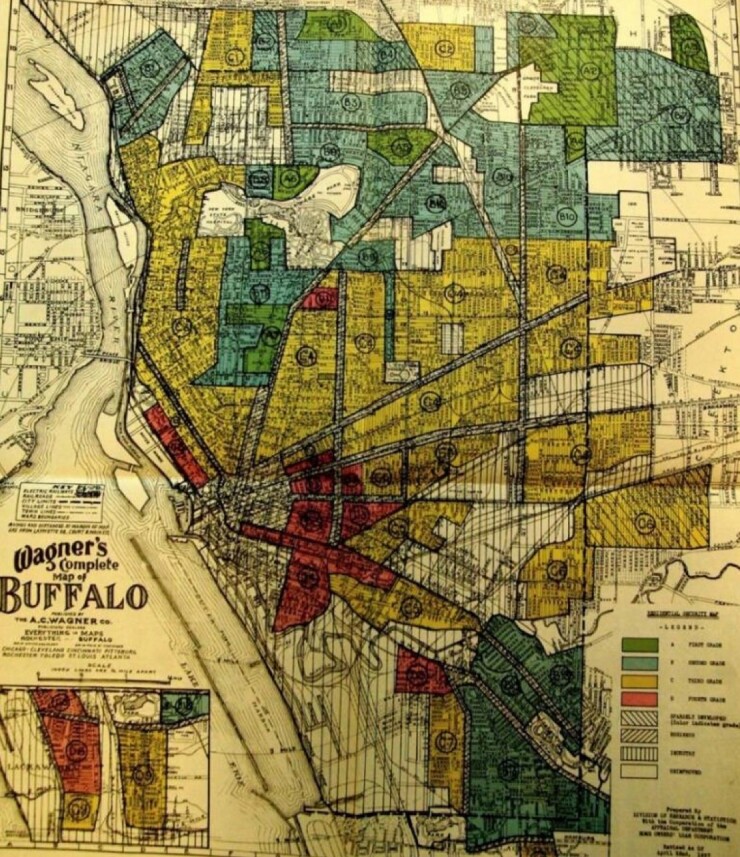

Historically there's been a one-sided relationship between banks and low-income communities. Banks would take deposits from residents and businesses there, offering minimal interest in return, but they frequently denied loans or provided high-interest, predatory loans to people in those same areas. When the CRA passed in 1977, Congress directed regulators to issue binding evaluations of how effectively banks lend to low- and moderate-income individuals.

One of the CRA's lead architects, Sen. William Proxmire, D-Wis.,

Despite its enactment alongside a string of civil-rights laws, the CRA does not explicitly incorporate race into its assessments. Jessie Van Tol, CEO of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, said the act is one of a set of laws enacted to address racial disparities, such as the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975, which requires banks to report data on home mortgage applications, approvals and denials to prevent discriminatory lending practices. Like the CRA, that law also faced pushback from the banking industry.

"[The CRA] was passed as a response to redlining, which was squarely a race-based phenomenon," Van Tol said. "At the time, the understanding of race and class in America was such that the response ended up being passed on sort of a class basis, on an income basis."

Van Tol noted another reason for the rule being pegged to income was that communities of all races have been left behind.

"These are not just communities of color, these are also poor white communities in Appalachia as well, places that either don't have bank branches today, or perhaps never had concentration of bank branches," he said. "Nonetheless, banks are lending in these places."

The industry-led suit argues that the Federal Reserve, the FDIC and the OCC exceeded their statutory authority when they

Banks have opposed aspects of the

Leach was disheartened given he sees the new CRA as an incremental improvement, providing clarity he believes could actually help the industry with compliance, especially smaller institutions.

"It's not this huge, cumbersome thing," he said. "Many of the institutions that were around and redlining back in the day are still ones that are fighting against this incremental improvement and claiming it's a huge inconvenience, and it's not…they just need to buck up and just get on with it."

Leonard Bernstein, a banking lawyer at Holland & Knight, said there may be a sense of unfairness among banks regarding the obligations imposed by the CRA, especially compared to non-banks.

"I think there could be a legitimate fairness issue among the banks, wondering why others in the industry don't have the same obligation," he said. "That is as much a political question as a business question, and that's been there from the start."

Regulators have echoed such sentiment about uneven CRA obligations. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau Director Rohit Chopra said in June he supports leveling the playing field between bank and credit union CRA requirements.

Van Tol — who said he was surprised by the lawsuit — noted that banks' opposition to the enhanced CRA rules fits into a pattern of pushback against civil-rights measures.

"The laws of the CRA can be placed in the context of the industry sort of fighting tooth and nail for specific and meaningful changes in policy that would produce better outcomes from a racial equity perspective," he said. "The rule was, I'd say, widely considered to be a compromise."

The Supreme Court's opinion overturning

"The bank trades have seen this shift in the Supreme Court, and have seen a path in the Fifth Circuit to bring favorable cases that you know, even if they wind up in the Supreme Court, perhaps have more favorable outcomes for business interests and you know, they have shifted and adjusted strategies accordingly," Van Tol said. "So far, that's kind of been viewed as a free punch — so to speak — at regulations that they don't like, and I think that has certainly emboldened them."

Van Tol said empowering judges to interpret the statute doesn't necessarily spell victory for the banking industry. After all, any stakeholder can challenge agency rules.

"In pursuing these really sort of aggressive court cases, they certainly run the risk of people like us bringing our own cases, pushing in the opposite direction," he said. "I think they run the risk also of really angering their primary regulators, who — it should be noted — don't change with the political shifts."