WASHINGTON — When banks resisted expanding credit in the years following the financial crisis and passage of the Dodd-Frank Act, online marketplace lending seized on what seemed like a niche opportunity: targeting the credit markets deserted by banks.

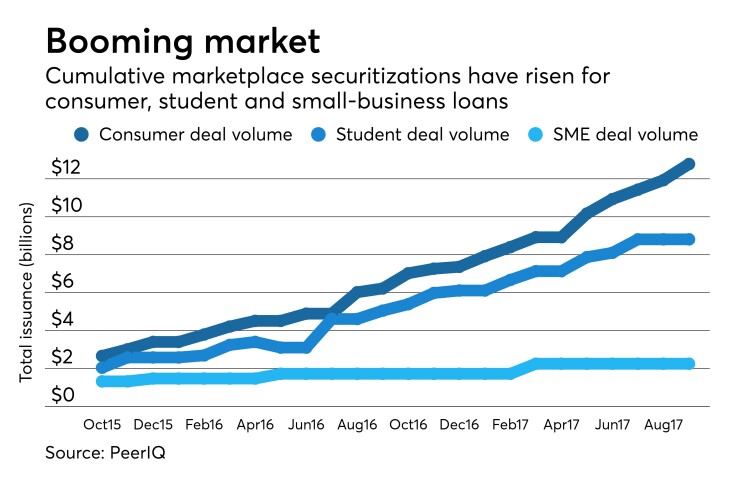

But with issuance of marketplace securitizations now exploding — rising 300% cumulatively in the past two years — the idea of online lending as a niche is quickly deteriorating. This continues to prompt challenging questions including whether the industry imposes systemic risk, how it can weather an economic crisis, whether its underwriting model is sustainable and if the days of bank-managed financial intermediation are numbered.

“We're fundamentally destroying financial intermediation, and we're only rebuilding parts of it back up again,” said Karen Shaw Petrou, a managing partner at Federal Financial Analytics.

Here are four questions about the future of online lending:

Can online lenders weather a true economic storm?

Online lenders have flourished in credit markets deserted by banks in the wake of post-crisis regulations. But as these new business models take root within the financial industry, concerns are growing about their chances of survival during the next capital drought.

“We've taken big chunks of risk out of the banking sector and moved that to the nonbanking sector,” said Ram Ahluwalia, the co-founder and CEO of PeerIQ, a company that tracks marketplace lenders. “Many of them will consolidate and disappear at the credit cycle turns.”

Today, online lenders have grown into important providers of products now shunned by banks, such as small business loans, personal loans and student refinancing. But, because they typically cannot rely on cheap sources of funding like deposits, they offload their loans to other players, such as asset managers, hedge funds and even community banks, spreading the risk to other corners of the financial industry.

Yet some question whether the success of the online lending model can be determined in the current economic environment, which has been relatively benign.

Underwriting methods developed to make loan origination cheaper, more efficient and accessible to a broader range of borrowers have yet to be tested by a credit crunch.

“The resiliency of the portfolios relying on alternative data and underwriting hasn’t been materially tested today by adverse market conditions,” said Keith Noreika, the acting Comptroller of the Currency, in an interview. “Nonbank lenders do share some similarities with institutions we saw in the financial crisis or prior to the financial crisis that caused trouble.”

Is online lending a recipe for systemic risk?

Whether online lending poses a new systemic risk is perhaps the most controversial question about the sector's future.

The potential of lenders to hit speed bumps from loan losses, a liquidity crunch and exhaustion of their capital is one issue. But how big an impact those problems would have on the overall financial system is another.

Some say the answer could lie in the magnitude of risk to banks that are the biggest purchasers of loans and securities from nonbanks. In the first quarter, banks funded 40% of all of Lending Club’s originations, according to the company’s earnings report. When banks purchase securities from an online lender, the risk of the underlying loans is spread across multiple institutions, yet the financial crisis proved that such diversification of risk does not make it go away.

The crisis showed that securitization can obscure risks across the industry and fuel the growth of unsustainable businesses. Observers said this could become a concern with online lending the more it is embedded with community bank balance sheets.

"Community banks lack risk management infrastructure to drive accountability on the loan performance and on the valuation of the loans,” said Ahluwalia.

But others argue that online lenders' footprint — even within the loan markets that they serve — is still too small to have any systemic effect.

“For this to be a systemic problem, these loans would have to be originated in very large volumes, and then sold into the banking system in very large volume and not be detected by the bank examiners,” said William Isaac, a senior managing director at FTI consulting and a former chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Since 2013, marketplace lending companies have securitized $12.8 billion in consumer loans, $8.8 billion in student loans and $2.3 billion in small business loans, according to PeerIQ’s third-quarter report on the industry. By contrast, banks held $9.46 trillion in loan balances at the end of the second quarter, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

“We're lending smaller loans than a traditional bank,” said Sam Taussig, the head of government relations and community banking at Kabbage. “So, the idea that we are rapidly taking over the entire small business consumer marketplace is pretty wildly inaccurate.”

The securitization model, he added, can help to spread risk, rather than concentrate it in the hands of a few companies.

“We're diversifying ... risk across many stakeholders,” Taussig said. He noted that once assets end up on bank balance sheets, they are also liable to be examined by regulators. “As you subject yourself to a bank partnership, you subject yourself to additional scrutiny by the federal regulators,” he added.

Is expanded access to credit enabled by online lenders a good thing?

At the 2016 Super Bowl, Quicken Loans ran an ad for its Rocket Mortgage product, showing people applying for mortgages on their phone while at the aquarium, at a show or at work. "If it could be that easy, wouldn't more people buy homes?” the ad says.

But the images of taking out credit as a casual endeavor sparked backlash on social media from critics who made comparisons to the recklessness of the subprime mortgage crisis, suggesting that online lending models are designed to approve borrowers too easily, and that their pricing is not affordable.

“Maybe we shouldn't make getting a mortgage so easy a child could do it (like in the ad),” one person wrote on Twitter, illustrating the suspicions raised by models that approve lenders maybe too smoothly.

But Taussig describes the easier credit access marketed by online lenders differently. He says they have become adept at finding creditowrthy consumers that banks may have overlooked.

“Fintech companies are offering products that, yes, sometimes are more expensive because we are extending loans to riskier customers that may not have access from a traditional institution,” said Taussig.

He argued that borrowers who use platforms like Kabbage are “not desperate for credit, they're desperate for time.”

“We're like the UPS of capital — fast, easy and a great experience,” he said.

According to a July research paper by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve, which analyzed consumer loans originated by Lending Club between 2007 and 2016, these products are indeed picking up where banks have left off.

“Fintech lenders fill credit gaps in areas where bank offices may be less available and provide credit to credit worthy borrowers that banks may not be serving,” the study found. “And this credit seems to be ‘appropriately’ risk-priced.”

Yet there have also been growing questions about the affordability of online loans. With only 15 states, plus the District of Columbia, enforcing usury caps on small-business loans, research has shown that rates on small-business loans in some places have reached as far as triple-digit rates.

“The cost of these loans is no different than the storefront payday loans,” said Scott Astrada, the director of federal advocacy at the Center for Responsible Lending. “When the market isn't regulated, bad actors are rewarded.”

But Taussig says most online lenders are taking affordability issues seriously.

“The first thing we look at, even before moving on in the application process, is the ability to repay,” he said, adding that the company values long-term customer loyalty. “Kabbage succeeds only when the customer succeeds.”

Still, critics of the industry are skeptical of the model’s resiliency.

“Small businesses are ... rolling over the loans and borrowing repeatedly,” said Todd Baker, a senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School and managing principal at Broadmoor Consulting.

“As soon as the credit cycle turns and losses start, the institutional funding for these lenders will dry up, and they will be unable to refinance and roll over those loans to these small businesses.”

Is traditional banking dead?

But if online lenders persevere and grow, the biggest question might be whether their expansion leads to a reconfiguration of the financial industry, with the traditional bank model of taking deposits to fund loans on borrowed time.

In other words, will banks no longer be the middleman for companies looking to borrow?

“When you have disintermediation it means that your financial system ceases to rely on regulated financial institutions with" deposit insurance and access to the Federal Reserve's discount window, said Petrou. "That's fine in good times.”

But, she added, long-term risks of such a fundamental paradigm shift include “lack of across-the-business-cycle lending capacity, lack of resilience under stress, lack of internal controls, lower growth rates due to higher cost credit, and much less credit for critical economic-equality sectors," like startup, small businesses.

At its most extreme, disintermediation could remove the need for banks in the financial industry. But that would inevitably boost the systemic risk of newer fintech players. Indeed, if new types of payments technologies take hold, they could become part of the core structure of the financial industry.

“Everyone wants to come up with a blockchain solution that everyone else has to rely on,” said Pratin Vallabhaneni, an associate at AKPS. “If a firm is actually successful on doing that, the question becomes whether that firm will be deemed systemically significant.”

But Taussig said disintermediation could also help even out risks in the financial system by providing a more diversified set of business models.

“Disintermediation of the banking system creates safety by diversifying risk,” he said.

But if the model of banking becomes fundamentally obsolete, then the regulators themselves will be disrupted.

”We have a regulatory system that grew up in a bank centric marketplace,” said Jo Ann Barefoot, a fintech consultant. “One of the biggest regulatory challenges is how to have holistic regulation of the whole market.”