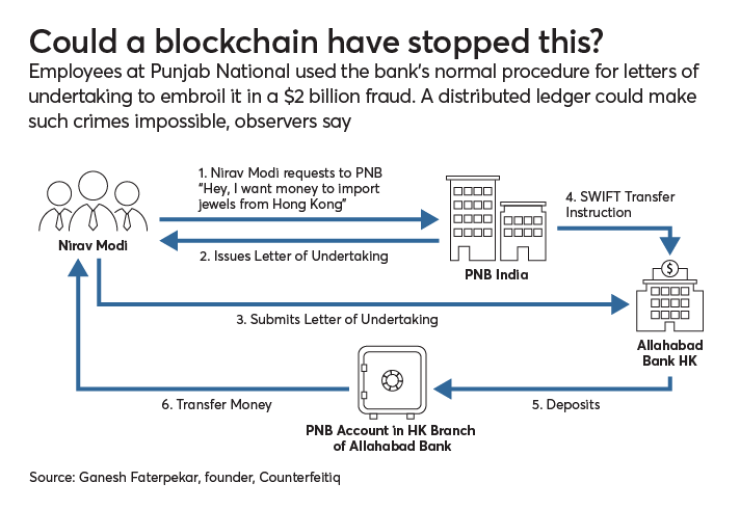

A massive fraud that cost India's second-largest bank at least $2 billion is highlighting concerns about vulnerabilities in institutions' internal controls and spurring some to claim that blockchain could have prevented the crime.

In a recent incident at Punjab National Bank, a deputy branch manager and his subordinate allegedly falsified 150 letters of undertaking directing other banks to give loans to a group of jewelry companies, with PNB providing surety for those letters. Virtually all of them defaulted, causing PNB to be on the hook.

What made the fraud so difficult to detect was that, as far as its internal systems were concerned, the transactions didn't exist. The letters of undertaking were sent using the Swift network, but none were recorded on PNB's internal record-keeping software, which wasn't linked to the Swift system.

That's why some are arguing that bockchain, or distributed ledger technology, could have prevented the fraud. Because immutable records are kept on a decentralized database that multiple parties can view, it's possible that the fraud either wouldn't have happened or could have been detected sooner.

“The whole concept of a distributed ledger system is based on providing mutual validation of transactions among a number of parties who are authorized to have secure access to the distributed ledger,” said John Verver, a consultant and adviser to the anti-fraud software firm ACL.

PNB, the lending banks, and the jewelry companies could all be part of a chain, and each one could see part of the transactions and receive notifications about them. Swift and central banks could also be part of the validation chain.

“At that point, it’s harder to have gaps in the process,” Verver said. “Everyone’s got insight into what’s going on here.”

Monica Summerville, senior analyst at Tabb Group, agrees it might have helped.

“Trade finance is a good use case for blockchain, because there’s so much paper and there are so many different parties in different geographical regions that have to have a trusted relationship,” she said. “With blockchain you decentralize, and the trust is built into the system. If you had a properly implemented blockchain end to end, this particular fraud could not have happened.”

In many banks, there are processes that aren’t fully automated and core systems aren’t linked to other systems, leading to an overreliance on humans. That also leaves it vulnerable to potential fraudsters, particularly ones inside the institution.

“Wherever you have that manual intervention, you need a lot of risk, governance, and oversight,” Summerville said.

That makes it a good test case for blockchain, she said.

“Blockchain might have maybe prevented some aspects of this fraud, but definitely it would have been discovered much faster,” Summerville said.

She recommended that banks turn to outside help for this, from vendors and consultants.

“The day of everybody building their own systems is over,” she said. “There are companies out there that could put systems in place quickly.”

What about employees determined to go rogue?

But not everyone agrees blockchain is potentially a silver bullet.

Chris Skinner, chair of the European networking forum The Financial Services Club, non-executive director of the fintech consultancy firm 11:FS, and author of several books on digital banking, is extremely skeptical of the idea that a distributed ledger could have stopped the Punjab National Bank fraud from happening.

“At the end of the day, a rogue employee will find some way to buck the system,” he said. “A distributed ledger will record an immutable transaction that the employee cannot change. But if the employee created the transaction fraudulently, then it’s the transaction that’s in question, not the immutable record. If you have employees who are rogue, that’s something you have to police internally, regardless of whether you’ve got distributed ledger technology or any other technology.”

Verver also acknowledged that technology can only do so much — even if all the letters of undertaking had been recorded in distributed ledgers, somebody at the appropriate level at PNB would have to keep an eye on them.

Summerville agreed that preventing fraud takes more than a blockchain.

“You could say this was a complete failure of basic governance principles, where you have to match your assets with your liabilities and make sure you have governance in place so that one person isn’t doing things unchecked,” she said. “Normally, there would be certain checks and balances in place, and in this case there’s a litany of best practices that the bank didn’t follow, nor did Swift, nor did the regulator.”

But she also pointed out that smart contracts built for a distributed ledger can be programmed with the ability to confirm clauses of a contract. They could also send data out to an analytics service to look for signs of fraud.

“That’s not unique to blockchain and it’s quite surprising that some of that doesn’t go on now,” she said. Swift, for instance, could be analyzing international payments all the time, looking for suspicious patterns.

Verver pointed out that sound internal controls, fraud analytics, and notification of fraud red flags could be layered on a blockchain.

“Take the case of PNB and the letters of undertaking,” Verver said. “If you used an appropriate distributed ledger system so that all parties involved were a part of that transaction and it’s validated, everybody agrees it’s a deal, at the same time you could apply analytics that are looking for indicators of fraud, and you could add another level of validation.”

Blockchain + human oversight

To truly prevent the type of fraud Punjab National Bank experienced would take distributed-ledger-style technology combined with human supervision and monitoring, fraud controls and fraud analytics, many said.

A distributed ledger’s smart contracts could be programmed to require sign-offs from specific people, Skinner suggested.

“If you’re trying to create a process that can catch exposures, then the more people involved in the process at sign-off, the lower the likelihood of exposure,” Skinner said. “It’s that balance between when do you need to empower and designate authority versus when do you need to have layers of authority. When I look at PNB or any of the instances of people begin pawned by technologists like Bank of Bangalore, it’s always the human element that’s the most susceptible to being duped. And that’s the big we have to crack down on. How do we stop the individual being stupid?”

It could take around five years for all the standards and agreements to be put in place to make blockchains work in trade finance, Skinner estimated.

“It comes down to how many institutions are involved in the agreements,” he said.

With blockchain technology overall, “We’ve put the horse on the racetrack and we haven’t worked out what the cart is,” Skinner said.

“It’s putting the technology first rather than working out what the technology process will work before we apply the technology,” he said. “A lot of standards and agreements between institutions need to be put in place.”

Verver agreed. “The tech companies and international standards bodies and regulatory authorities and businesses are all going to come together around this, so it’s going to take some time. Sometimes you need somebody to go ahead and say, hey, we’re going to make something here that works, it won’t be perfect, but let’s get going.”

Editor at Large Penny Crosman welcomes feedback at