September 2008 was one of those rare interludes when the world shifts beneath your feet. Markets froze. Fabled banks stood on the precipice. The U.S. government, after initially standing by idly, brought out its bazooka. After a generation of deregulation, it genuinely seemed possible that the U.S. banking system would be nationalized.

The crisis had immense economic and political consequences over the following decade.

But 10 years later, what's remarkable is how little the financial crisis changed Americans' relationship to debt and savings. We still borrow more and save far less than prudence would dictate.

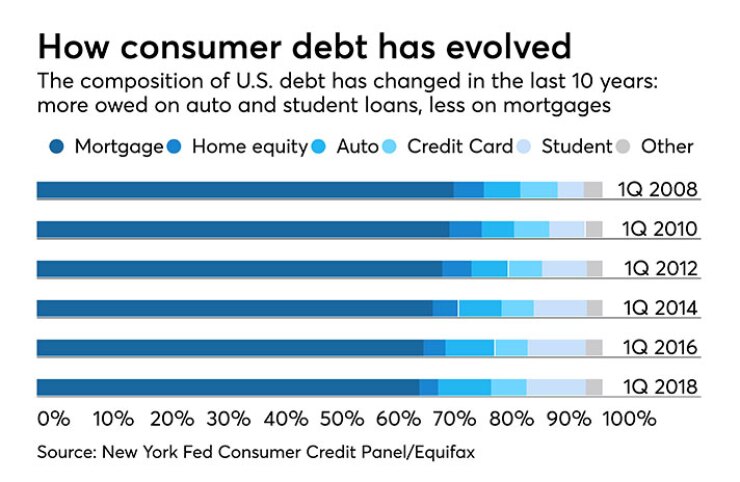

U.S. household debt, which declined between 2008 and 2013, has rebounded sharply. By the first quarter of 2018, it was at an all-time high of $13.2 trillion. The composition of our debt has changed, and we've been better able to manage our obligations, thanks in substantial part to an extended period of low interest rates. But the crisis did not teach us a lesson about the perils of borrowing too much.

Nor did it lead us to place more value on savings. Between 1960 and 1984, the U.S. personal savings rate — which is savings as a percentage of disposable personal income — never fell below 8%. That level of national thrift is far out of reach today. In December 2017, the personal savings rate dropped to 2.4%, its lowest level since the debt-fueled boom of the mid-2000s.

In a much-discussed Federal Reserve survey that was published last year, 35% of U.S. adults reported that they would not be able to pay all of their bills if faced with a $400 emergency. Given that context, one can only hope that the next downturn will be far less severe than the last one, because Americans are again exposed.

"Ten years ago, a lot of the problems economically for households were sort of covered up in debt," said John Thompson, chief program officer at the Center for Financial Services Innovation. "And it sort of feels like that's starting to happen again."

Unable to save

After the financial crisis, some observers argued that Americans were entering a new era of frugality, in which lenders would not be able to rely as heavily on interest income. And for a time it appeared Americans were changing their money habits. A survey that was conducted by the Consumer Federation of America in February 2009 found that 44% of consumers were making an effort to pay down their debt, compared with 38% the year before.

"To state the obvious, consumers went through a severe shock," said Harit Talwar, the head of Marcus, the consumer finance arm of Goldman Sachs. "I've been in various focus groups over the last 10 years, and heard consumers directly. It's very personal. Everybody knows somebody who really struggled."

But it is unclear whether consumers changed much at all, even in the short term. The personal savings rate climbed as high 11% in 2012, but that proved to be a temporary blip, which was likely caused in large part by lenders writing down delinquent consumer debt.

When Americans' expenses fell in the post-crisis era, discretionary spending increased more so than savings, as two studies from the JPMorgan Chase Institute illustrate.

In the first study, the institute, which uses customer data from the New York-based megabank to research economic trends, identified more than 4,300 consumers who had an adjustable rate mortgage that reset to a lower interest rate between April 2010 and December 2012.

Over a two-year period, those customers increased their credit card usage so much that the spending hikes exceeded their mortgage-related savings by 4%.

The second study looked at the spending habits of more than 25 million Chase credit card and debit card holders during a period in late 2014 and early 2015 when gasoline prices were on average $1 per gallon lower than they had been a year earlier. The researchers found that individuals spent roughly 80% of the money they saved at the gas pump.

Diana Farrell, the institute's CEO, lamented that many Americans do not understand the need to establish a base level of spending that is below their income. "A lot of people don't necessarily have a good grip on their finances," she said in an interview.

Certainly wage stagnation during the post-recession period has made it difficult for families to save. That is particularly true in lower-income households, which also have been squeezed by rising costs for housing and higher education.

And to analyze consumer behavior in isolation is to miss a big part of the picture — namely, how outside factors shape that behavior.

"Consumer behavior is largely like water. We kind of take the path before us," said Mariel Beasley, co-director of the Common Cents Lab at Duke University, which applies insights from behavioral economics to the study of Americans' financial well-being.

In the age of targeted marketing, retailers have become highly skilled at persuading us to open our wallets. In comparison, efforts to encourage frugality, such as America Saves Week, are modest. "Savings in this country is invisible," Beasley said.

Banks and other lenders also have a big impact on consumer behavior. Consider, for example, the steep rise in automobile debt after the crisis — outstanding car-loan balances rose by 76% between the first quarter of 2010 and the same period eight years later, according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Undoubtedly some people delayed making car purchases until after the crisis ended. But the rapid growth in auto loans was likely more attributable to an increase in the available supply — lenders took note of the high percentage of car owners who made their loan payments on time during the crisis and subsequently loosened their standards — than it was to changes in the demand for transportation.

The comparatively small market for secured credit cards provides another example of how the financial industry has been encouraging consumers to favor debt over savings.

Secured cards are designed for individuals who do not qualify for mainstream credit. Before getting access to a line of credit, customers put down a security deposit, which serves as a savings mechanism. But secured credit cards are being used by only a tiny fraction of consumers who could benefit from them, according to a 2016 study by the Center for Financial Services Innovation.

One key reason is that credit card issuers do little marketing of secured cards, which tend to have low or even negative profit margins in the first year or two, the study found. So consumers who could benefit from secured cards may turn instead to high-cost payday lenders.

"Arguably the greatest barrier to increased uptake of secured credit cards is their invisibility to most consumers," the study's authors wrote.

Myths about millennials

The Great Recession was particularly hard on Americans who were coming of age in the late 2000s. Those who'd just graduated from college were saddled with staggering levels of student debt and facing a weak job market. Those who hadn't finished college fared even worse, since they were competing against their better educated peers for low-wage work that was in short supply.

In recent years, two narratives have taken hold about the effects that the financial crisis had on millennials' relationship with debt. There is reason to be skeptical of both, though.

The first narrative is that millennials, because they went through the crisis at an impressionable age, are more wary of credit card debt than older generations. In a LendingTree survey from 2015, only 61% of millennials reported that they had at least one credit card, compared with 79% among members of Generation X and 89% among baby boomers.

But there may be numerous reasons that millennials have fewer credit cards, starting with the fact that they have been trying to dig out of a financial hole and are less likely to qualify for mainstream credit. "Younger consumers are generally less creditworthy," said Ezra Becker, a senior vice president at TransUnion.

Another factor in millennials' relatively lower reliance on credit cards is the fact that older generations established their spending habits at a time when debit cards were far less common than they are today. Also a potential culprit: a 2009 federal law that restricted the ability of credit card issuers to market their products on college campuses.

The second narrative that has emerged since the crisis is that millennials are less interested in owning a home and a car than previous generations. The more likely scenario is that many millennials have resigned themselves to delaying major purchases that previous generations made at younger ages.

Young adults often are still trying to pay off their student loans, and many of them are living for longer periods in cities, where car ownership may be optional. Meanwhile, mortgage standards have tightened, and home prices are soaring in many parts of the country.

A 2017 survey by TransUnion found that 74% of millennials who did not already have a mortgage planned to buy a home eventually. "A set of specific circumstances has resulted in a generation that has postponed the typical milestones of adulthood — job, home, marriage, children — and all the purchases that go along with them," said a TransUnion report on millennials.

Across all U.S. consumer groups, home equity is probably the realm where the crisis had the biggest long-term impact on financial behavior.

Before 2008 many Americans saw their home equity as a way to finance consumption or speculate in real estate, but that is far less true today. A recent LendingTree study found that 43% of consumers who tap into their home equity

"I think before the financial crisis, many, many, many American consumers saw their home as a bit of a piggy bank," Brad Conner, vice chairman of the consumer banking division at Citizens Financial, said in an interview. "Obviously it was a very rude awakening to folks."

How much of that shift is the result of consumers' own experiences during the Great Recession, as opposed to lenders tightening their lending standards, can be debated. Conner said that both factor into the current dynamic.

The broader question is whether the crisis dimmed America's love affair with homeownership. But even 10 years later, it is perhaps too soon to provide an answer.

The national homeownership rate plunged from 69% in 2006 to 63% in 2016, a trend driven by the millions of Americans who could no longer afford their bubble-era mortgages, the tighter lending standards that emerged after the crisis and the rise of single-family rental homes.

In the first quarter of this year, the U.S. homeownership rate was back above 64%, which was almost exactly its 30-year average between 1965 and 1995.

Looking ahead

Conversations about U.S. consumer debt often focus on whether another bubble is forming, and whether the next crisis is around the corner.

Right now, there is no sign that the sky is about to fall. Mortgage-related loans, which make up about 71% of the nation's consumer debt, no longer rest on the assumption that house prices will rise forever. Delinquency rates remain low across various asset classes thanks in large part to a strong labor market. And as a percentage of disposable income, household debt is near its average from 1990 to 2018.

The big question is what will happen to consumer debt levels as the Fed continues to raise interest rates. In an optimistic scenario, Americans who have been unable to earn a decent return on their savings over the past decade will start to sock away more of their earnings.

In a gloomier future, U.S. consumers will continue to borrow freely even as rates climb. The ability to make their debt payments will erode with time, which will leave them vulnerable to the next economic shock. And then the same cycle that has unfolded over the last decade will begin again.