-

Banks have faced onslaughts of litigation for several years over their credit card payment protection plans. But so far legal efforts to challenge or change the business have ended in dismissals or relatively small settlements.

February 6 -

Discover Financial Services is anticipating a joint enforcement action from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau over the marketing of its credit card payment protection products, the company disclosed in a regulatory filing posted late Thursday afternoon.

January 26 -

WASHINGTON - The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency issued a rule Tuesday that could give banks a large share of the $6 billion a year credit life insurance business.

September 18 -

First Premier Bank has for decades offered credit cards with higher rates and fees than almost any other bank. For instance, if you borrowed $250 on one of their cards and held that balance for a year, you'd pay roughly 75% of that amount, $187.50, in finance charges and fees—assuming no late payment or other charges.

December 20

For a product claiming to protect consumers from unforeseen misfortunes, banks' credit card payment protection plans have made plenty of enemies. A federal probe could give those opponents the upper hand for the first time.

Attorneys general and plaintiffs' lawyers have

But thanks to a series of regulatory and judicial decisions favorable to the banking industry, defeating or settling the legal complaints has historically been cheap. Compared to annual profits of $1.3 billion on payment protection products, the industry's tens of millions of dollars in legal costs are a rounding error.

"There is no incentive for getting out of this business unless or until the regulators get in," says Scott Hakala, managing director for consultancy CBIZ Valuation Group LLC and an expert witness for plaintiffs' attorneys seeking to calculate alleged injuries to payment protection customers.

The possibility that the government may do just that

The potential stakes include not only the immense profitability of payment protection plans, but the regulatory framework that has allowed the products to thrive.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau "is trying to move consumer financial services regulation from a disclosure-based regime to more of a fairness-based regime," says Joseph Barloon, a partner at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. "There is every indication that this is an area where we may see that philosophy put into action."

"LIFE HAPPENS"

Payment protection products are advertised as a safety net for consumers worried that an unexpected misfortune could send them over the brink.

"Life happens," says Discover Financial Services on its

"Our optional protection products have benefits that offer cardmembers tools to monitor and understand their credit, which helps to provide peace of mind," says Discover spokeswoman Leslie Sutton.

The company is responding to the federal probe by "working through the process with regulators and [we] remain focused on providing our customers with the products they value and service they expect from Discover," she said in a separate emailed statement.

For consumers, the plans function like insurance policies. Issuers who sell the product either waive or defer credit card payments for customers who suffer one of a number of covered events, from the birth of a new baby to job loss or death.

For the privilege, Discover charges 89 cents for each $100 outstanding on a consumer's credit card every month he is enrolled. Other major card issuers charge as much as $1.35 per $100 per month. Currently, 24 million accounts, or roughly 7% of credit cards issued by the nine largest issuers, are enrolled in some form of payment protection, the Government Accountability Office estimated in a

Discover claims that it has over one million enrolled customers, and the company has earned the revenue to prove it. Since Discover's 2007 IPO, revenue on debt cancellation and deferment plans has skyrocketed. The credit card company posted $241 million in revenue on the products in the fiscal year ended Nov. 30, 2011, which was more than triple the $74 million reported in 2007. (Discover says that some of the growth in the latter two years is due to the addition of reported income from securitized loans under new accounting rules.)

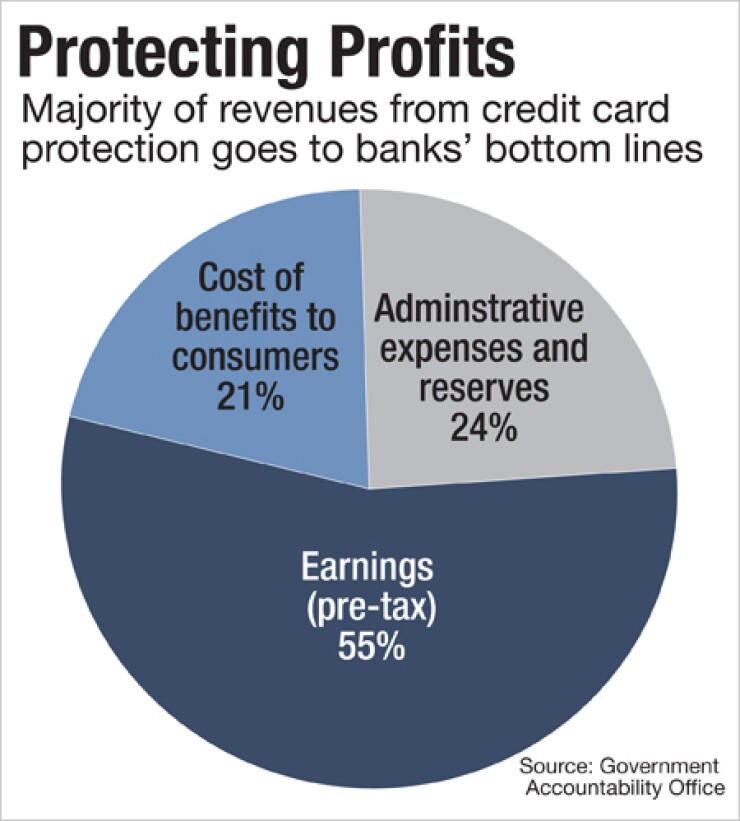

The top nine card issuers posted $1.3 billion in pretax profits on the plans in 2009, or more than half of the $2.4 billion collected in fees paid by enrolled borrowers, according to the GAO. Almost a quarter of the fees collected go towards the cost of marketing and administering the plans. The remaining 21% of fees, or about $518 million annually, are spent providing the plans' actual benefits to consumers.

The revenue inflow from debt protection plans has likely taken on increased importance for issuers following the 2009 passage of the Credit Card Accountability, Responsibility, and Disclosure Act, which restricted credit card lenders' ability to charge fees and hike interest rates.

"Given the CARD Act and the way the revenue model [for credit cards] has generally changed, these products are likely to be getting more focus," says Sarah Phelps, a principal at First Annapolis Consulting.

"A lot of these credit insurance products do drive some revenue for the issuers. As any good business owner would do, if one line item were to come under pressure, issuers look to other line items to replace some of that revenue," she says.

Just about half of all credit card mail offers include the option to sign up for payment protection, according to data from Mintel Comperemedia, a company that provides direct marketing data.

The only company to scale back on payment protection plan offers is JPMorgan Chase & Co., which "significantly reduced" its payment protection marketing on its Freedom and Slate credit card products starting in March 2011, Mintel reports. The bank, which agreed to pay $20 million in December 2010 to settle litigation against its plan, declined to comment.

Representatives for Bank of America Corp. and Citigroup Inc. also declined comment for this article. American Express Co. spokeswoman Leah Gerstner said in an email that the company has not been and is not presently involved in litigation over its protection plans, but declined to speak further about the products.

A spokeswoman for Capital One Financial Corp.

"We're pleased to have worked with Attorney General McGraw to resolve this matter which dates back to a time prior to 2006. We've since made significant improvements in the payment protection product and look forward to continuing to serve our card customers in West Virginia," said Capital One's Tatiana Stead in an email statement. She refused to comment further on the product or the company's 2010 settlement of class-action litigation over product sales.

FROM INSURANCE TO 'PROTECTION'

Few retail banking products boast profit margins rivaling credit payment protection plans, yet many banks didn't get into the business until the 1990's.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency authorized some bank debt cancellation contracts as early as the 1960's, but state insurance regulators argued that the products constituted a form of credit life insurance, and thus were subject to their oversight.

Whether the plans were insurance or banking products was more than a matter of semantics. If the products were insurance, they were subject to state rules often mandating that their price be proportional to the claims paid. But if they were banking products, they could be sold with whatever terms and pricing banks wished.

During the 1990's, an 8th Circuit Court ruling and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act reinforced the OCC's claims,

Insurance companies' sales of credit card insurance plummeted from $757 million in 2001 to $186 million in 2009 - and big banks jumped into the breach.

"The large national banks just went after it in a big way, and they had the backing of the OCC," says Birny Birnbaum, executive director of the Center for Economic Justice in Austin, Tex., who has heavily criticized the products over the last decade.

The OCC declined to discuss its oversight of debt protection.

DOUBTS RAISED

Debt cancellation and deferment products are typically marketed without disclosing much of the initial fine print. Some, but not all, lenders post the full terms and conditions online, but seven of the nine largest card issuers would not mail out copies unless a consumer enrolled in the protection plan, the GAO found.

Some protection agreements require customers who have suffered debilitating injuries to prove they remain injured by submitting a new doctor's note every month. Several plans dictate that any customer who files for benefits due to unemployment will immediately have his credit line frozen or reduced.

"I have yet to see [a plan] that made economic sense to the customer," says Hakala, the expert witness. He argues that the products should be sold for closer to 29 cents to 39 cents for every $100 of debt for the benefits consumers receive; that's close to what credit unions charge for similar products.

But it's not just the terms of the product or the prices that have consumer advocates up in arms. Card issuers have been

Overblown is how banking industry executives characterize consumer advocates' criticisms. The product is optional and provides tangible value to the consumer, bankers argue.

"A remedy for the consumer who feels he's paying too much for something is to stop paying for it," says Kevin McKechnie, executive director of the American Bankers Insurance Association, a subsidiary of the American Bankers Association.

"These things were designed for people who couldn't get life insurance. There's significantly less underwriting involved," he adds. "Go and try to find a life insurance policy for $5,000 that diminishes as you reduce debt. This is the only place in the market where you can find that kind of risk protection."

The GAO notes that the products can also shield consumers from credit score dings in a short-term cash crunch, and that they can offer some borrowers peace of mind. Industry members accentuate other positives, and they have readily refuted consumer advocates' claims that the products are worthless. Plaintiffs' attorneys often fall back on arguments that the plans are too expensive. Even assuming they did make a compelling case, pricing is not the court's jurisdiction.

"There's a difference between not-a-good-value and valueless - it's not like customers were buying acreage on the moon," says Gregory Dresser, a partner at Morrison & Foerster LLP, who has helped defend banks, including Capital One, against some of the payment protection class-action complaints.

NEW SHERIFF

Battles over the merits of the products have for the most part remained outside of courtrooms, and the vast majority of the dozens of lawsuits filed have either been dismissed or settled quickly (

"Most of the actions and private litigation are based on how these products are marketed. People who either have scripts that are really misleading or deceptive or those who clearly don't follow the scripts," says Rick Fischer, a partner with Morrison & Foerster LLP. "Those sorts of things are not going to hurt the people offering legitimate products."

Fischer, like other banking industry members, instead points to the CFPB as the most dangerous agent of change.

The 2009 Dodd-Frank Act transferred supervisory and enforcement authority for credit card debt protection products to the CFPB, and consumers advocates and banking industry members alike point to the bureau as the next front line in the payment protection war.

"The greatest risk is they [CFPB officials] go beyond just pure unfair marketing or deceptive marketing and go after the economics of the product itself, because then they can destroy it," Fischer says.

"The bureau has already made it clear that it is focused on these products and the issue of 'consumer confusion,'" says Anand Raman, a partner with Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom.

Discover announced in January that it is

CFPB spokeswoman Jennifer Howard says the agency is "currently reviewing" changes to disclosure rules for debt cancellation and suspension agreements proposed by the Federal Reserve for its Regulation Z in 2009 and again in 2010, before power was handed over to the CFPB. She declined to comment on the joint enforcement action with the FDIC against Discover.

"The GAO found that consumer costs for these credit card debt protection products might be substantial relative to the benefits. One of the CFPB's priorities is making sure that consumers have clear information about the costs and risks of these products," she adds.

Both the joint enforcement action and the review of Federal Reserve regulations appear to stem from the ongoing concern over how the products are sold. Even if regulators demand substantial tweaks in marketing and disclosure of payment protection programs, those changes are unlikely to undermine the profitability of the plans and would allow banks to protect a business that brings in billions of dollars in profit in an increasingly regulated credit cards market.

"The question is what tools [the CFPB] will use. Over the next several years, I would expect both enforcement with respect to perceived Unfair, Deceptive and Abusive Practices and rulemaking, focusing on disclosures and marketing," Raman says.

The new "abusive" standard added under the Dodd-Frank Act

"The bureau has suggested in some statements that 'abusive' goes to price…. And that's where I think the greatest risk is" for debt protection products, says Morrison & Foerster's Fischer.

The products would be dramatically less profitable if regulators were to set price restrictions akin to those used at the state level for insurance or to require lenders to significantly boost the benefits the products provide to borrowers. Banks, which are currently reaping profit margins of 55% on average, could easily withstand some new restrictions on the products - but it is unclear how much new regulation they would be willing to put up with in order to continue selling what amounts to an auxiliary product.

"The more that [regulators] require issuers or insurance companies to include certain bells and whistles, and the more value they demand at a minimal price, the less likely you are to have the product," Fischer says.

Direct price ceilings or explicit restrictions are also just one potential tool in the regulator's toolbox. Skadden's Raman notes other products that have been pushed to the margins.

"Bank regulators have shown, for example with payday lending and

As banks that once specialized in offering tax-time refund anticipation loans have found, once-lucrative products don't always manage to stay that way, especially if they find themselves in a regulator's cross-hairs.

For now the success of the payment protection is undeniable. The products have the backing of the OCC, millions of subscribers and provide banks with hefty payouts.

But just as Discover tells its customers that "life happens" when selling them payment protection, it and other credit card lenders now may find the future hard to predict for the product itself.