A battle over director compensation is brewing at a recently converted thrift in New Jersey, showing that it doesn’t take long after going public for an activist investor to make waves.

In a recent letter to Kearny Financial in Fairfield, N.J., longtime activist Lawrence Seidman argued that directors have profited unfairly from its

“Someone has to draw the line,” Seidman said in an interview. “Do I think the bank is doing a good job? No.”

-

Citigroup said its board changed the way the lender calculates performance pay for executives after receiving some complaints.

April 6 -

Kearny Financial in Fairfield, N.J., is moving ahead with its second-step conversion after getting approval from the Federal Reserve Board.

March 16 -

A rush of bank M&A is welcome news to activist investors, who typically make money when banks make improvements and sell to bigger institutions. Here is a look at six firms that have stood out in recent years for pressuring management teams and boards to enhance value for shareholders.

January 31 -

Activist investors are turning their sights back toward banks after going easier on them than on other industries in recent years. Look for the next bank M&A wave to be fueled by aggressive hedge funds as they push for board seats and ultimately sales of financial institutions.

January 31

It’s a standard play for Seidman, who has a

But some observers argue that Seidman’s move is premature. The $4.4 billion-asset Kearny has only been a fully public company for 11 months – it had been trading as a mutual holding company since 2005 – and has a pile of capital on hand from its conversion. It will simply take time for the company to deploy that capital.

“It’s absurd to criticize a company for low returns” after it just completed a conversion, said Mark Fitzgibbon, an analyst with Sandler O’Neill. “Activist shareholders have an agenda – what that is remains to be seen.”

Kearny executives did not respond to requests for comment. Seidman declined to disclose his stake in the company.

Investor complaints about compensation are not unusual, but typically they are directed toward management. Across the industry, investors have complained about escalating executive compensation – and won concessions – as tight margins have weighed on performance. Citigroup, for instance, recently

Seidman, though, is tapping into a

“Let me put it to you this way: They’re not the only bank that over compensates,” said Ted Kovaleff, a longtime industry observer and owner of the investment firm Informed Sources Service Group. Kovaleff is also an investor in Kearny.

In an 18-page letter to Kearny's president and chief executive, Craig Montanaro, Seidman outlined in extensive detail his concerns about compensation at Kearny.

When the company began trading as a mutual holding company in 2005, the board received a stock incentive plan, according to the letter. Options tied to that plan were exercised when the company went public last May.

As part of the second-step conversion, directors are set to receive an additional incentive plan this fall.

Such plans are typical for mutual conversions, and compensation levels are highly regulated, according to William Bouton, an attorney with Hinckley Allen.

According to Seidman’s letter, each board member receives approximately $100,000 in annual cash compensation, in addition to the stock incentive package.

Over the past decade, most directors received between $1.5 million and $3 million in total compensation, according to the letter. John Hopkins – who served as CEO until 2011 and currently serves on the board – earned more than $12 million.

Seidman has other concerns as well. He accused Kearny freezing its pension plan for company employees in 2007, but keeping a separate retirement plan in place for directors

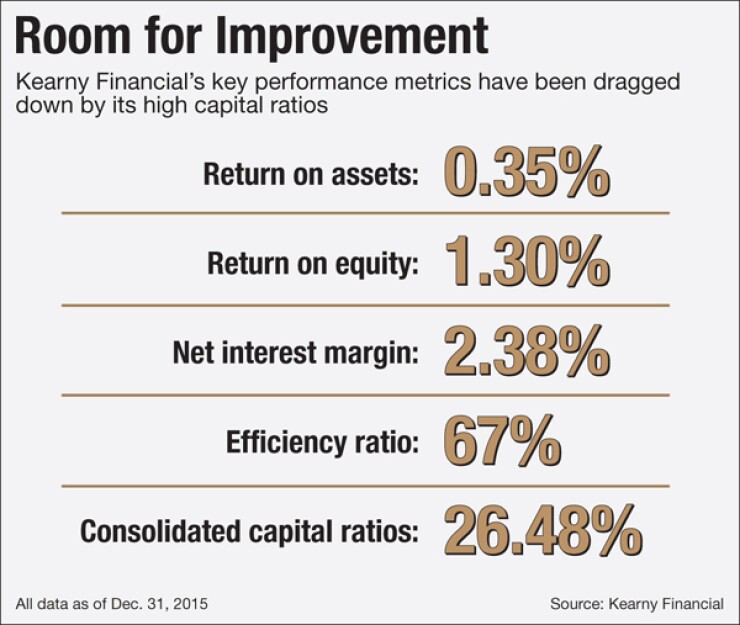

Kearny has struggled to keep pace with its peers. Though its profits for the quarter that ended Dec. 31 increased more than 75% from the same period a year earlier, to $3.8 million, its return on equity fell 44 basis points, to 1.30%. Since 2006, its ROE has never exceeded 2.17%, Seidman said in the letter.

Still, Fitzgibbon said investors should be patient and give Kearny some time to prove its value.

“Kearny is a newly public company that has a mountain of capital – and that’s because the way the conversion process works,” Fitzgibbon said. “It’s not through any fault of theirs.”

The company’s tangible common equity ratio is nearly 25% – one of the highest in the nation, Fitzgibbon wrote in a recent client note. And it is making moves to deploy capital. Assets have increased 25% over the past year as Kearny has sharply increased its lending.

Fitzgibbon also noted that Kearny has not formally published its compensation plan. Instead, it has provided only preliminary details as part of its prospectus, according to Seidman’s letter.

“It’s premature to criticize a plan that hasn’t yet been presented to shareholders,” Fitzgibbon said.

In most second-step conversions, shareholders vote on incentive plans for directors one year after the company goes public. The plans typically win easy approval from investors, Bouton said.

Any pushback on director or executive pay – from either activists or advisory firms – typically occurs a few years down the road, after the company has more of a track record.

But “the business is changing,” Bouton said. “There’s been an increased focus on executive compensation from dissident shareholders.”

Like most converted thrifts, Kearny is prohibited from selling for three years after going public. Bouton said he believes Seidman is trying to drum up discontent among shareholders now in order to gain support for a sale down the road.

“It’s obviously a prelude to sell the bank at an earlier date than what management would like to see,” Bouton said.