-

Branches are outdated, expensive and unwieldy. For years, bankers have postponed dealing with the dead weight. Now it looks like theyre starting to make the necessary hard decisions. Finally.

December 17 -

A new report from Celent finds that many banks plan to expand their branch networks over the next few years even though all the evidence suggests that foot traffic is declining and that most transactions are now conducted online.

May 9 -

New research from Synergistics points out the unintended consequences of branch closures.

May 9 -

A number of banking company closed branches during the second quarter, and even more have announced plans to follow suit. Over the past 12 months, there was a net loss of about 770 branch offices nationwide as banks aim to cut costs in the face of depressed interest rates and low loan demand.

July 30

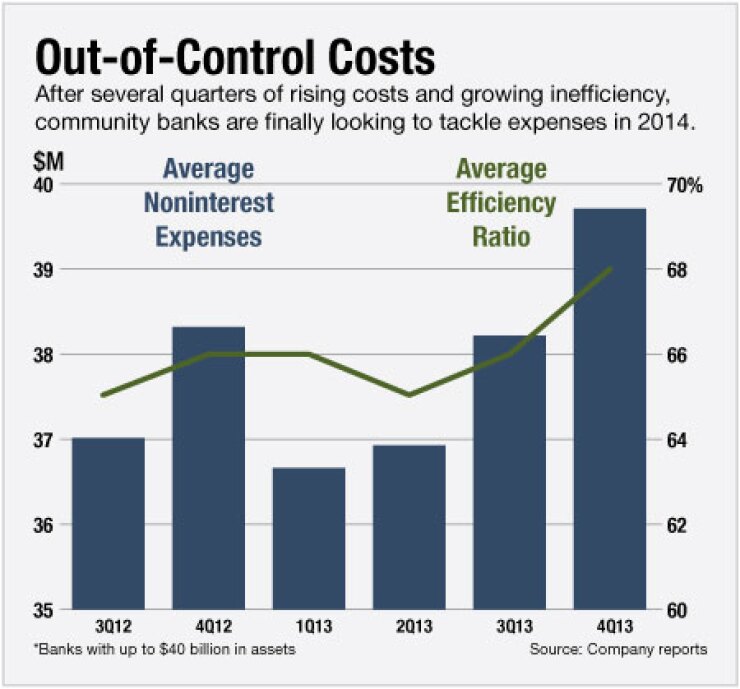

Community banks are often reluctant to close branches, but rising costs are encouraging management teams to take a hard look at cutting back.

Noninterest expenses at banks with $40 billion or less in assets rose nearly 4% in the fourth quarter compared to a year earlier, averaging $36.9 million, according to data compiled by American Banker. Higher costs have been a drag on efficiency. The average efficiency ratio was 68.26% in the fourth quarter, compared to 66.46% a year earlier.

Up-to-date statistics on branch closings at community banks are scarce, but recent announcements suggest that

"It is broadly recognized now that it isn't the 1990s anymore and that things need to change," says Bob Meara, senior banking analyst at consulting firm Celent. "The competitive advantage of having branch density is a huge cost disadvantage."

Fulton Financial (FULT) in Lancaster, Pa.,

Other

CenterState Banks (CSFL) in Davenport, Fla.,

Closings are also a natural way to slim down after acquisitions.

Simmons First (SFNC) in Pine Bluff, Ark., said it

Despite the latest closings, many industry observers believe that community banks lag larger rivals in the area of branch consolidation.

"More community banks may be cutting branches, but not enough and not quickly enough," says Collyn Gilbert, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods.

Smaller banks have frustrated analysts with their reluctance to close branches. Partly as a result of consolidation, the average number of branches per community bank has been rising, peaking at 5.6 branches in the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.'s latest report on the sector.

Many larger banks began pruning far earlier and have become active consolidators. A number of those banks greatly expanded over the last decade and now have more fat to trim than smaller rivals, industry experts say.

"Big banks are going to be doing the bulk of the closing because [they] were responsible for the branch boom," Meara says.

Smaller banks expanded their networks more cautiously than big banks during the early 2000s. Total U.S. branch count rose 24% from 2001 to 2011, to 83,128, according to the FDIC. But community bank branches rose less than 3% over that time, to 35,851. (The agency's most recent study on community bank branches runs through the end of 2011.)

Big banks are scaling back.

Webster Financial (WBS) in Waterbury, Conn., is one of the few community banks to show comparable zeal for closing branches, Gilbert says. The $20 billion-asset company, which has shed more than 50 branches in recent years, has implemented a staffing model to make its network leaner, Chairman and CEO James Smith told analysts this month.

Webster remains an exception among community banks.

"Small banks have been able to grow earnings, which has caused them to turn a blind eye" to branches," Gilbert says. "But you just can't have these expansive branch structures if branch traffic keeps falling."

Mounting expense pressure will change attitudes, industry observers say. But a reluctance to cut, along with the time it takes to secure regulatory approval, end leases or sell properties, means that large-scale branch consolidation at smaller banks "is still several years away, if it happens at all," says Brad Smith, president of bank consulting firm Abound Resources.

"I don't expect to see any dramatic decline in the near term," Smith says. "Almost every metric would suggest we are saturated with branches in lots and lots of marketplaces, yet community banks are still loath to close branches."