It’s a scene you might find in any American coffee shop.

Baristas steam milk and pour espresso shots. Students and young professionals sipping on Peet’s Coffee set up laptops at small tables, ready to hunker down and work, while other patrons pop in for a quick caffeine fix or a bite on their way to work.

It seems so ordinary, if it were not for a few Capital One Bank employees lingering in front of a large screen at the back of the store. Armed with tablets, they stand ready to answer questions about banking products and services, yet they avoid approaching people with a hard sell.

This cafe, in Boston’s Downtown Crossing, is leased and managed by Capital One Financial in McLean, Va. It is one of more than two dozen cafes that the $366 billion-asset company operates in markets where it otherwise has no branch presence.

The coffee shops are

The cafes represent another threat to community banks as larger institutions rely more on their deep pockets and technological know-how to take market share. Since they are not branches, the storefronts are easier to open and less expensive to operate. And they are popping up at a time when interest rates are rising, making it more important for banks of all sizes to bring in low-cost funding.

“If you can imagine people popping these things up — the competition for community banks would get overwhelming,” said Robert Mahoney, CEO of the $2.5 billion-asset Belmont Savings Bank in Massachusetts, which has a branch less than two miles away from Capital One’s cafe in Harvard Square.

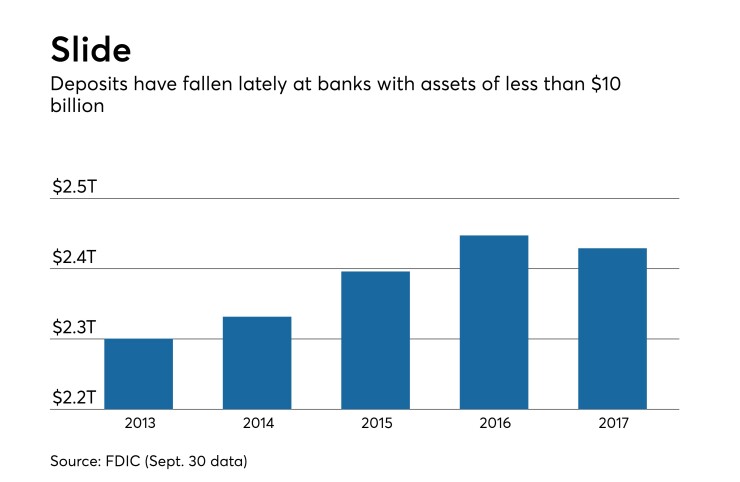

Community banks have already been losing ground, with deposits at institutions with less than $10 billion in assets decreasing by about 1% over the 12-month period that ended Sept. 30, according to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Banks with more than $10 billion in assets reported a 4.5% increase over the same period.

A look at Capital One’s deposit growth shows the success of its digital bank, which it obtained from its 2012 purchase of ING Direct. Deposits at its digital bank rose by nearly 27% over a four-year period that ended June 30. All of the company’s other branches had total deposit growth of 8.6% over those years, including a negligible increase over the 12 months that ended June 30.

Several factors have worked in Capital One’s favor.

The cafes fall short of the definition of a branch, defined as a place where deposits are received, checks are cashed and money is lent, according to the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. Prospects can open accounts at Capital One Cafés, but the only way they can deposit cash into their accounts is through the ATMs.

The distinction is important because branches are held to certain regulatory obligations, including an approval process with a comment period. Branches also must report deposit volume to the FDIC. Since Capital One doesn't report the cafes' deposit volume to the FDIC, it's impossible to know how much market share they are taking in a given market.

The lack of vaults, teller lines and other branch staples reduces Capital One’s overhead.

The innovative hybrid offers a branch substitute that appeals to millennials, said Ken Thomas, president of Community Development Fund Advisors. It's only a matter of time before more big banks replicate the model, he said.

“We cannot stop innovation,” Thomas said. “There will be more of these — not fewer.”

In fact, Bank of America in Charlotte, N.C.,

“I just think it’s a really good way to introduce people to financial services, particularly if you’re an out-of-state firm and you’re just opening a coffee shop,” said Kevin Tynan, senior vice president of marketing at Liberty Bank in Chicago. He noted that the insurer State Farm has a similar concept with its Next Door cafe.

“It’s particularly helpful to them because it overcomes those barriers people see,” Tynan said of the State Farm cafe.

While the concept has the potential of expanding banking services to more millennials, it is also creating anxiety among community bankers, including some who believed that the cafes were considered branches.

“Next thing you know, there are five banks on every street corner,” Mahoney said. “Maybe that’s a great convenience for the public, but from a community banking standpoint, it has the feel of unfair competition.”

Another Boston-area banker, who asked not to be named, also complained that the cafes should be treated the same as branches.

Some industry observers said the rise of cafes and other tech-heavy offices signals a need to update certain regulations, including the Community Reinvestment Act, which was written in the 1970s and updated in the 1990s before online banking became commonplace.

“This is yet another reminder that we need to update CRA to be not so branch focused and to look at new deliveries opening up,” said Jo Ann Barefoot, a consultant and former deputy comptroller of the currency. "Evaluation of compliance with CRA is very subjective."

Capital One, for its part, isn’t skirting CRA. The deposit-taking ATMs in Boston qualify Massachusetts to become part of its CRA assessment area. Capital One’s most recent CRA rating is from 2013, which took into account an evaluation that occurred before most of its cafes opened.

Though most, if not all, of the Boston cafes are in affluent neighborhoods, Capital One noted when it

Capital One also has cafes in Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Denver, Seattle, Philadelphia, West Palm Beach, Fla., and St. Cloud, Minn.

“I suspect you'll continue to see us testing how can we take advantage of fewer branches that give us an opportunity like in Boston where we've got a number of cafes, but we don't have any branches per se,” Scott Blackley, Capital One’s chief financial officer, said at an investor conference last summer.

That would allow Capital One “to accumulate deposits and … customers without” branches, Blackley added.

A Capital One spokeswoman said by email that the company plans to add more cafes this year in a range of cities, though she did not discuss specific markets or the number of offices planned. She also declined to say how many deposits come from the cafes.

Smaller banks should take time to observe Capital One’s effort and implement their own strategies to trim costs and create economies of scale.

“This is the way the industry is moving,” Thomas said. “There are more competitors and nonbanks competitors like fintechs. Capital One has come up with a unique way to compete with fintechs because [the cafes] are less expensive than opening the full blown branches they would normally open.”

Tynan offered a similar suggestion for community bankers — put coffee shops in branch lobbies.

“Many lobbies now are too large and don’t have as much traffic, so putting five or six tables in there and offering free coffee is a signal to the community to come in and visit,” Tynan said. “You need to figure out ways to bring them into your branch, and certainly I think a coffee shop concept is a good way to do that.”

Pinnacle Financial Partners and Trustmark did just that, with each adding Starbucks cafes to their branches in Memphis, Tenn., said Carter Campbell, president and chief manager of National Property Concepts, which offers consulting services tied to branch design.

“This allows banks to save money on some of these properties and also draw foot traffic,” Campbell said. “It helps banks grow deposits and all they are trying to do in branches.”