By any measure, WSFS Financial in Wilmington, Del., has been a community banking standout under the leadership of its chairman, president and chief executive, Mark Turner.

It has been highly profitable, consistently posting industry-leading returns on assets and equity, largely because management decided during the depths of the financial crisis to accelerate its growth while many others were retrenching.

WSFS is also among the industry’s most respected banks, as evidenced by the stack of awards it has received for customer service and employee satisfaction.

Yet for all its recent success, the $7.1 billion-asset WSFS appeared to be at a crossroads when management set out earlier this year to map out its next strategic plan. The nagging question facing senior leaders: How can WSFS keep the momentum going at a time when loan demand is sluggish, competition for customers is intensifying and consumers, particularly millennials, are increasingly favoring large banks that are seen as having more sophisticated technology than their smaller counterparts?

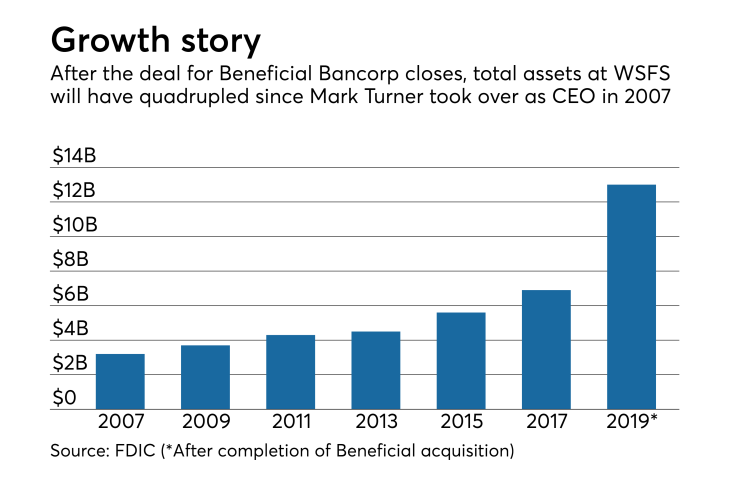

The answer came in August, when WSFS announced that it was buying the $5.3 billion-asset Beneficial Bancorp in Philadelphia for $1.5 billion.

The acquisition, expected to close early next year, would be WSFS’ largest to date, almost doubling its asset size, to nearly $13 billion, and vastly increasing its visibility and deposit share in the nation’s eighth-largest metropolitan market.

But what makes the deal for Beneficial especially compelling is the estimated cost savings, which WSFS intends to use to fund what Turner calls its “tech transformation.”

Within six months of the deal’s closing, WSFS intends to consolidate about 30 overlapping branches and begin investing half the savings — roughly $32 million over the next five years — in a host of customer-facing and back-office technologies. The goal is to improve the delivery of retail services and help WSFS chip away at big banks’ dominance.

“If you look at Bank of America or JPMorgan Chase, they are already taking most of the new entrants into the marketplace,” Turner said in a recent interview. “We are not losing customers, but we are not getting our fair share of new ones coming into the market.”

Read about the other Best in Banking honorees for 2018:

If the Beneficial deal meets projections, it could position WSFS as a consumer and commercial banking powerhouse in the mid-Atlantic for years to come.

Once the acquisition closes, WSFS would leapfrog over M&T Bank and BB&T to claim the No. 6 deposit share in the Philadelphia area, which is dominated by national banks. Even with the planned branch consolidation, WSFS would still have more than 110 branches in Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey, and the addition of Beneficial’s balance sheet would give it nearly three times the lending capacity of any other community bank in the market.

It’s a potentially transformative deal and, as the driving force behind it, Turner is being honored by American Banker as one of its community bankers of the year for 2018.

Engineering a transformation

The recognition also acknowledges the extraordinary job Turner has done leading the 186-year-old WSFS over the past dozen years and building — through a series of acquisitions and partnerships — what was in many ways a traditional local thrift into a modern, high-performing community bank.

On Turner’s watch, WSFS has expanded into Pennsylvania and New Jersey, added several new business lines, including a thriving wealth management operation, and teamed with fintechs to offer such products as online student loans and online home equity loans. It also took advantage of marketplace disruption — most notably Wilmington Trust’s sale to M&T in 2011 — to add teams of lenders who brought with them new commercial customers.

The acquisition of Beneficial would be the biggest deal of all — and Turner’s last as CEO.

Though just 55, he is stepping down from the post at the end of this year and handing the reins to Chief Operating Officer Rodger Levenson, 57. Turner will stay on as executive chairman, but give up day-to-day responsibilities to focus on business development for WSFS and economic and workforce development in the markets it serves.

Turner was named CEO in 2007 and before that spent three years in what was called the office of the CEO under his predecessor, Marvin “Skip” Schoenhals. Turner told the board years ago that he planned to stay in the role for no longer than 15 years and he said he is stepping away now because Levenson, who he had been grooming for the job since 2014, is more than ready.

“In my opinion, 10 to 15 years is the optimal amount of time to be the CEO of a public company,” Turner said. “If you stay too long, you run one or more of the following risks: becoming complacent, becoming arrogant, losing energy or becoming irrelevant.

“The world is moving pretty fast these days and you have to stay on top of your game mentally,” Turner added. “Even though Rodger is a couple of years older than me, he brings a different energy, a different view and a different vision.”

Pivoting after the financial crisis

An accountant by training, Turner joined WSFS in 1996 as comptroller under Schoenhals, was promoted to chief financial officer in 1998 and named COO in 2001. Over the course of the next several years, Schoenhals gave his protégé a range of responsibilities — appointing him head of retail banking at one point and head of technology and operations at another — to broaden his experience and better prepare Turner for his eventual promotion to CEO.

Then, just a year after Turner took the helm, the housing market crashed and triggered the Great Recession.

Like most banks, WSFS suffered steep losses on real estate loans during the crisis, but some crucial decisions made in the years prior — selling off a subprime mortgage subsidiary in 2003 and intentionally scaling back its construction lending in 2005 — helped it weather the downturn better than most.

Then once WSFS got a handle on the credit problems, Turner and the management team decided in 2010 that it was time to focus on growth.

Over a two-year stretch, WSFS hired dozens of relationship managers, added de novo branches and relocated others to better locations. It also entered the wealth management business with its acquisition of Christiana Bank & Trust in Greenville, Del. WSFS would go on to acquire three more banks, including its first two in Pennsylvania, and two other wealth management firms in the next several years.

Levenson, who joined in 2006 from Citizens Financial, said that WSFS would not be in the position it is in today if Turner had not decided to switch from defense to offense in 2010.

“A lot of banks were hunkered down trying to figure out what was going on, but once we got our arms around the credit, Mark said, ‘Let’s go after it,’ even though it meant that our earnings would be depressed for a couple of years,” Levenson said. “That took a lot of courage from management, and from our board.”

Added Turner: “We felt like that was the best time for us to be investing in our future.”

The success of the strategy has been evident in steadily improving profitability numbers. This year’s third quarter was one of its best ever. Net income nearly doubled from the same period a year earlier, to $38.9 million, and its core return on assets, excluding some one-time gains, climbed by more than 50 basis points, to 1.72%.

WSFS’ numbers look even better when measured against the overall industry. Through the first half of this year, its return on assets was 24 basis points higher than the industry average, at 1.57%, and its return on equity was 163 basis points above average, at 13.46%, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. data.

Fostering employee engagement

Turner is understandably proud of the returns WSFS has produced, but he’s even more proud of the culture he has helped to create at the bank.

Fifteen years ago, when Turner was COO, WSFS brought in the Gallup Organization to measure employee engagement, and the initial results were discouraging. For every three engaged employees at the bank, there were two disengaged employees.

Schoenhals and Turner responded by adopting a series of measures that empowered employees to make decisions to better serve customers and encouraged them to publicly celebrate the work of their colleagues. By the time Turner took over as CEO, the numbers had improved dramatically: 29 engaged employees for every two disengaged employees.

The numbers have held up over the past decade and they help explain why WSFS has been named a top workplace in Delaware by the Wilmington News-Journal for 13 years running and a top global workplace by the Gallup Organization for three consecutive years.

The culture of engagement that Turner helped foster was never more evident than on the day after Thanksgiving last year.

Because of a processing glitch, direct deposits that WSFS customers were counting on that Black Friday did not make it into their accounts, and many didn’t find out until their debit cards were declined while they were out Christmas shopping.

The bank was bombarded with phone calls from angry customers looking for answers — on a day when many call center employees had taken personal time off. So Peggy Eddens, the chief human capital officer, and her team called all the employees who had scheduled days off and asked them to come in and help handle the flood of calls and help soothe customers’ nerves. Every single one of them showed up, according to Eddens. (The glitch was fixed by 11 a.m.)

In a social media post a few days later, Turner praised the employees who “rallied to make a bad situation better.” He also took full responsibility for the glitch, never once placing blame on the bank’s core processor, and that resonated with customers.

WSFS’ “transparency and ‘customer-first’ mentality are reasons why we will continue to bank with them for years to come,” one customer wrote in a comment on the post.

Eddens shared a similar story of employee selflessness that occurred several years earlier, when rival TD Bank’s direct-deposit platform malfunctioned on the day it closed its acquisition of Commerce Bank.

Many of TD’s branches were overflowing with customers demanding an explanation, and some employees of other local banks tried to capitalize on the unrest by encouraging the angry customers to ditch TD.

To Turner, though, it felt unseemly to kick a rival when it was down, and he instead instructed WSFS employees to go to nearby TD branches to lend moral support and offer to do whatever they could to help. Some WSFS employees ended up working at TD for several days, until the processing glitch was fully resolved.

It was an unprecedented act of kindness that WSFS has, until now, never made public.

“Doing the right thing is one of our core values,” said Eddens. “And sometimes that takes you to places, like a competitor’s bank lobby, that you wouldn’t normally go.”

Turner said that WSFS’ culture is its “secret sauce,” but he acknowledges that maintaining it is among the biggest challenges the bank faces as it integrates Beneficial. WSFS plans to take at least six months after closing the acquisition to change signs on Beneficial branches and convert systems, because Levenson said it needs at least that long to properly train Beneficial employees and introduce its brand to the marketplace.

Eddens and WSFS’ retail banking executives also have been upfront about the fact that jobs will be lost once the banks are fully integrated. In the weeks after the deal was announced, they traveled to every Beneficial location to discuss the branch consolidation plan and encourage employees whose jobs may be at risk to consider other opportunities within WSFS.

“We were very honest in telling them that there is overlap and that there won’t be jobs for everyone,” Eddens said. “It’s a hard message to share, but I think these truthful conversations really start to plant the value of culture.”

Making the deal work

The deal certainly has skeptics. WSFS’ stock price has soared in recent years because of the record profits, but the shares started falling after the Beneficial deal was announced, partly because some investors worry that the acquisition will suppress earnings in the near term or that the tech investment will take too long to pay off. (The stock has fallen by roughly 25% since early August.)

Frank Schiraldi, an analyst at Sandler O’Neill & Partners, said he understands why some investors may be skeptical.

'If we do everything just like the big banks do, we’ll lose,' Turner says.

While WSFS has plenty of experience with acquisitions, it has never integrated a bank as large as Beneficial, he said. Moreover, Beneficial is just three years removed from a second-step mutual-to-stock conversion and, as such, is flush with capital that WSFS would need to find ways to deploy if it hopes to hit its profitability targets.

“It’s a show-me story at this point,” Schiraldi said.

Even so, the analyst sees the deal as a good bet. “Ultimately I think it will be proved out as successful,” said Schiraldi, who has a “buy” rating on the stock. “There’s a lot of growth potential in Philadelphia, and there’s an opportunity for a sizable community bank to do well there.”

In his new role as executive chairman, Turner said that a big part of his responsibility will be “making the Beneficial acquisition work.” He is a Philadelphia native, and he intends to spend significant time in and around the city developing and rekindling relationships with business and civic leaders and prospective clients.

He also will be keeping close tabs on WSFS’ tech transformation. Two years ago, he went on a three-month “learning tour” in which he visited a wide range of financial, technology and retail firms to gain insight into how they were embracing innovation, and he came away from it believing that WSFS needed to up its game.

“You can open a deposit account online with us, but it’s clunky — it takes 20 minutes,” Turner said, identifying one of WSFS’ top tech priorities. “There are products out there that can do it in three, four or five minutes, and that’s what we need to be moving toward.”

He said, too, that in some cases WSFS needs to go beyond doing what other banks are doing to create unique experiences for customers. One idea: a click-to-chat feature in a mobile app that would allow customers to converse with a banker face-to-face.

“If we do everything just like the big banks do, we’ll lose,” Turner said.

Turner plans to spend about 40% to 50% of his time on board duties for community organizations, including serving on the board of Wilmington Leadership Alliance, a nonprofit he co-founded that provides job training to at-risk young adults.

During the rest of his waking hours, he will be thinking hard about what he wants to do once he steps down as chairman, likely within the next two years. Turner has no plans to join or start another bank — “I would never want to compete with WSFS,” he said — but he could envision a second career in which he invests in and advises startups.

“I feel like I’ve got one good act left in me and I’d rather start that at 55 than 65 or 70,” he said. “I’m not exactly sure what that act is, but I’m hoping it’ll be something interesting and a little less regulated.”