-

Two recent deals in Southern California serve as a billboard announcing that the mergers and acquisitions market there is shifting to open-bank deals.

July 28

Chiefs of healthy community banks say they are talking more about doing deals with rivals hurt by the tepid economic recovery.

At an industry conference this week in New York, executives at banks with less than $20 billion of assets gave anecdotal evidence that a much-expected wave of unassisted deals may be nearing.

Conditions that would lead to regulator-free acquisitions ripened last quarter: Lending fell. Balance sheets shrank. Revenue declined. Share prices stayed depressed. And failed-bank deals got pricier.

The result: Struggling banks are a lot more interested in selling the franchise — before regulators come calling. There is a sense that "live" mergers — those that do not involve failed banks — could accelerate by yearend.

"The boards and their executive teams are tired. We're starting to see discussions pick up," said Carl J. Chaney, chief executive of the $8.5 billion-asset Hancock Holding Co. in Gulfport, Miss. "I'm getting more and more calls from investment banks."

Chaney, speaking at a Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc.-sponsored community bank conference, said he gauges the temperature of the bank M&A market by the volume of deal books that investment bankers send his way. By that measure, the sell-side of the market is much hotter than it was just four months ago, he said.

Exactly when talk will become action remain's anyone's guess.

A few things are hampering normal deal activity. The continuing glut of bank failures is one. Figuring out what an unprofitable or barely profitable institution is actually worth is another. Doing a normal deal is still a leap of faith without many recent deals to compare prices with.

"I think there are a lot of people talking," said David Zalman, the chairman and CEO of Prosperity Bancshares Inc., a $9.6 billion-asset company in Houston. "Valuation continues to be the big question."

Also, few potential buyers stayed healthy by taking big risks. The same fragile economy that is pressuring sellers could discourage buyers from making a move.

"We don't want to mess up our bank," said Bernard Clineberg, the chairman and CEO of Cardinal Financial Corp., a $2.1 billion-asset Tysons Corner, Va., firm.

Clineberg has a couple of criteria for a deal target.

The first: "It would have to be a strong leader in charge of that institution."

The second: "It would have to be safe."

Clineburg said Cardinal is open to buying banks as well as insurance providers, real estate brokers and other businesses that can drive revenue growth.

The industry is poised for a big consolidation wave, he said, as regulatory changes cut revenue, pressuring the boards of market laggards to sell.

"I see it coming now," he said.

Fred Cannon, a co-director of research at Keefe Bruyette and its chief equity strategist, said the ingredients are in place for normal deals.

Consumer and business borrowing is down and will not rebound any time soon. Margins are shrinking as deposits swell and lending dries up. Regulatory changes are hurting income and expenses. Potential buyers, meanwhile, have lots of liquidity to deploy after raising capital.

"Consolidation should be the natural result of [all] that," Cannon said.

For many, failed bank are losing their allure as targets even as they dominate most of the merger activity, bankers said.

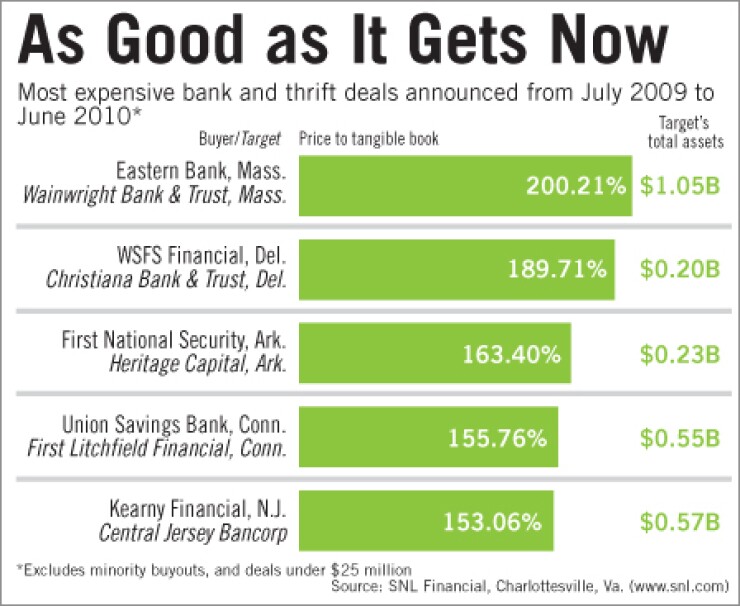

Loss-sharing agreements with the federal government are becoming less favorable. More bidders are entering the fray, driving up deal prices. The banks that have failed lately tend to be the smallest institutions, operating in markets that healthy banks do not like.

"The FDIC deals — the economics are going away," said Russell A. Colombo, the CEO of Bank of Marin Bancorp in Novato, Calif. "I think by the end of this year you are going to see more live deals."

Philip Wenger, the president and chief operating officer of Fulton Financial Corp. in Lancaster, Pa., said the $16.6 billion-asset company is bracing for a wave of normal mergers over the next 18 months to two years.

"There's more chatter," he said. "Folks need more capital. People [on boards] sit around and say: 'How are we going to get a return to our shareholders?' "

Fulton has not been all that interested in buying failures. Wenger said only a few banks have failed in his region. They tend to be damaged goods that have lost most of their best customers, he said.

"We're much more interested in what I would call healthy banks," he said.