-

Bankers, technology CEOs and President Obama are throwing everything they have at countering the growing threat of cyber attacks, putting their faith in biometrics, tokenization and data sharing. But it's far from clear that it will be enough.

February 13 -

Hackers in several financial services industry data breaches targeted customer-contact information that is often thought of as less sensitive. But crooks can use that data and other bits of stolen info to do great harm.

February 10 -

Criminals who once focused on email fraud are turning to text messages and phone calls to trick bank customers. Fraudsters are also using social media and Big Data to learn more about their consumer and commercial targets.

February 4

Bankers should act quickly to ensure they are not vulnerable to the same kinds of attacks that allowed a gang called Carbanak to steal $1 billion from financial institutions around the world.

The hack, which was revealed this week by Kaspersky Lab, relied on relatively unsophisticated forms of intrusion like fake e-mails, but also reflected an exceptional degree of patience and intelligence-gathering. Hackers lurked in bank networks for long periods of time in some cases since 2013 and secretly recorded bank employees to learn how they work and mimic their behavior.

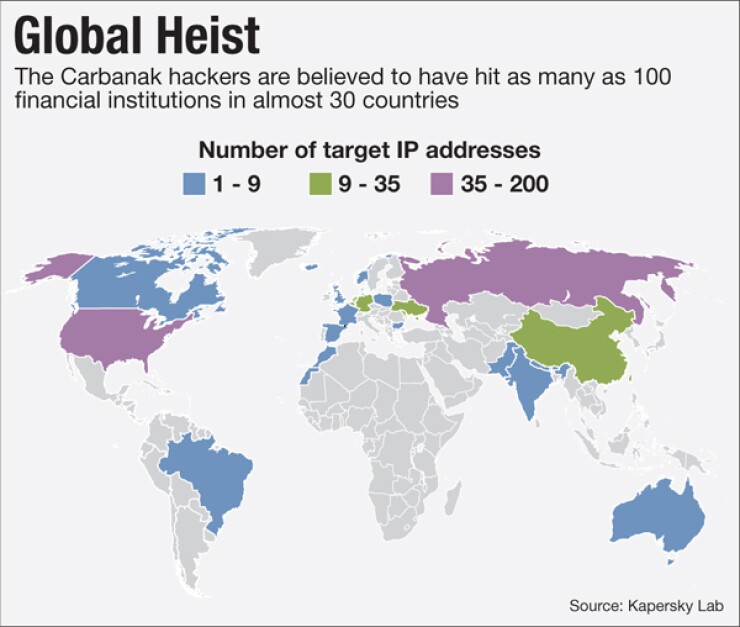

Kaspersky's researchers would not disclose the names or origins of affected banks but said about 100 financial institutions in 30 countries had been targeted so far.

Following are answers to questions about how banks can understand the threat posed by Carbanak and take appropriate action to guard themselves against it.

How are Carbanak hackers breaking in to banks' networks?

The hackers used so-called spear-phishing attacks, in which hackers send an email that appears to be from an individual or business that the victim knows. Once a victim clicks on an attachment, malware is launched on that person's computer. In the Carbanak case, the fake emails appeared to be coming from someone else within the bank and the attachments contained malware that exploited a vulnerability in Microsoft Word. Once inside banks' systems, the hackers were able to unleash malware software designed to carry out espionage, data exfiltration and remote control.

The espionage component let hackers take over the video cameras on victims' computers and secretly videotape them as they worked, over many months.

"This allowed the attackers to understand the protocols and daily operational tempo of their targets," Moscow-based Kaspersky

Why are so many bank employees still falling for spear phishing attacks?

Although spearphishing attacks are an old form of cybecrime, hackers are getting better at them, according to Avivah Litan, vice president at the tech consulting firm Gartner.

"They are using clever social engineering techniques to pull them off," she said. "For example, it is relatively easy for hackers to figure out who the CEO and managers of each bank are, and then use those names and identities to impersonate email senders."

A common technique, Litan said, is to make the email appear as if it's from the company's CEO with a title that an employee who is being spearphished can't resist such as "2015 Salary Plans" or "Urgent: your attention is required."

"Emails such as these are becoming commonplace techniques hackers use to infect employee desktops, and they succeed almost every time," Litan said. "It takes a lot of training to convince your staff to question emails from their CEO or other higher-ups they report to."

How did hackers manage to go undetected on banks' networks for more than a year?

The Carbanak gang conducted what's called an

"These thefts are a significant evolution in approach, since the attackers didn't simply break in, take over accounts, and run with the money," said Mike Lloyd, the chief technology officer at security analytics company RedSeal. "The time invested by criminals in studying the operations of target banks shows two things: first, that such attacks are lucrative enough for this time commitment to be worthwhile, and second, they would not have bothered if they did not have to."

How is the money being stolen?

Criminals are using online banking or international e-payment systems to transfer money from the banks' accounts to their own. In one case, the stolen money was deposited at banks in China and the United States.

In other cases cybercriminals have logged into banks' accounting systems, inflated account balances and pocketed the extra funds through a fraudulent transaction. For example: if an account has $1,000, the criminals change its value so it has $10,000 and then transfer $9,000 to themselves. The account holder doesn't suspect a problem because the original $1,000 is still there.

In another variation, cyber thieves seize control of banks' ATMs and order them to dispense cash at a pre-determined time. When the payment is due, one of the gang's henchmen is waiting beside the machine to collect the payment.

How can banks defend themselves against Carbanak?

The most important step is to tell employees not to open suspicious emails, especially if they have an attachment. This may seem obvious, but it has become painfully clear that many employees are still not getting the message.

"While this cyberheist is considered very sophisticated, spear-phishing is one of the most preventable and affordable," said Stu Sjouwerman, CEO of security consulting firm KnowBe4. "You would expect the finance industry to set the bar very high and have employees trained within an inch of their lives not to fall for such an attack. We would highly encourage financial institutions to take a look at their training methods and beef them up accordingly. "

Kaspersky also recommended that banks update their software. Carbanak has been exploiting a vulnerability in Microsoft Word for which Microsoft has already issued a patch.

Banks can also

"The lesson for defenders is clear: we need to up our game, understanding how we can be spied upon, and how motivated adversaries can work to hide in plain sight," said RedSeal's Lloyd. "Employees will always be prone to being fooled, as they were at the victim banks in this case. Organizations need to strengthen internal network segmentation, so that the whole chain does not fail whenever one weak link usually a human gets caught out."