A few years ago, certain members of the economics blogosphere, fascinated with bitcoin but frustrated by its volatility, began arguing that the decentralized digital currency needed a central bank to stabilize its value. More radically, some suggested that central banks should start issuing their own digital currencies as a replacement for paper money.

The constant fluctuation in bitcoin's price seemed to militate against its usefulness as a medium of exchange. But the Federal Reserve, went the argument, could peg its own digital currency at a rate of one-to-one with the U.S. dollar. This "Fedcoin" would be legal tender, just as banknotes are.

The idea soon escaped the blogosphere and spread through the cryptocurrency community, where it has won supporters such as Adam Ludwin, the CEO of Chain, a startup that is building blockchain architectures for financial companies. Researchers at the Federal Reserve, the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England have since studied the issue, and have even built proofs of concept to explore the possible future of central bank money.

"The idea is a fascinating one, and it looks like the 21st-century analog of paper currency," Jerome Powell, a member of the Fed's board of governors, said recently.

A stable, cashlike form of electronic money allowing instant and final settlement of transactions has obvious appeal for consumers. Central bankers, for their part, are interested in the idea of Fedcoin because a digital fiat currency would allow them to slash operating costs, fight financial crime and, when necessary, set interest rates well below zero. It could be the key to creating a cashless society. But they remain wary of distributed ledger technology, which is still in a nascent state, and unsure of what effect a Fedcoin would have on the private banking system — or on society as a whole.

Last November, the research arm of R3, a consortium of banks that are seeking to adapt blockchain technology for the financial industry, shared with its members a report shedding light on Fedcoin. The study R3 commissioned, which has not previously been made public, breaks down the potential benefits, risks and challenges of implementing central bank-issued digital currencies.

Digital dollars

Bitcoin does a remarkable job of replicating in the digital realm many of the key features of cash, namely censorship resistance, which means that people holding cash

Sina Motamedi, one of the first economists to explore the idea of central bank-issued digital currency,

Fedcoin, of course, would face no such uphill battle.

"There would be no need to 'convert' back to some underlying 'real' dollar because these digital dollars would be real, just in a new medium," Ludwin said in a talk he gave to an international audience of central bankers and regulators at the Fed's offices in Washington last June. "In the same way that dollars already exist today in multiple mediums — notes, coins, electronic reserves — we would treat these digital dollars as just dollars in a new medium, backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government."

Nor would Fedcoin interfere with the regular functioning of the central bank's monetary policy, as some critics have feared that bitcoin could if it became popular enough. New Fedcoins would be introduced into the economy by swapping them for banknotes — one dollar for one Fedcoin. As demand for Fedcoin fluctuated, the central bank would simply redeem the public's banknotes for digital currency, and vice versa, with the Fedcoin

Barring changes in monetary policy, then, the combined quantity of cash in society, both digital and physical, would remain constant. And because Fedcoins could be converted back into banknotes, they would no more impede the Fed's ability to guide the economy by setting interest rates on reserves than would the introduction of a new banknote denomination.

"It would be like if the Fed started issuing a $30 note," said JP Koning, who authored the R3 study and once worked at the Bank of Montreal, a member of the R3 consortium. "Would that have any influence on bank monetary policy? No."

A cashless society

If anything, the replacement of banknotes with digital cash could actually strengthen the Fed's hand.

As the demand for Fedcoin rises, the central bank would be able to cut down on the unavoidable costs of creating, storing and shipping banknotes, as well as the need constantly to upgrade their security features in order to protect the nation's money from counterfeiters.

"If they can figure out how to create digital money, they can sell off their printing presses," Koning said.

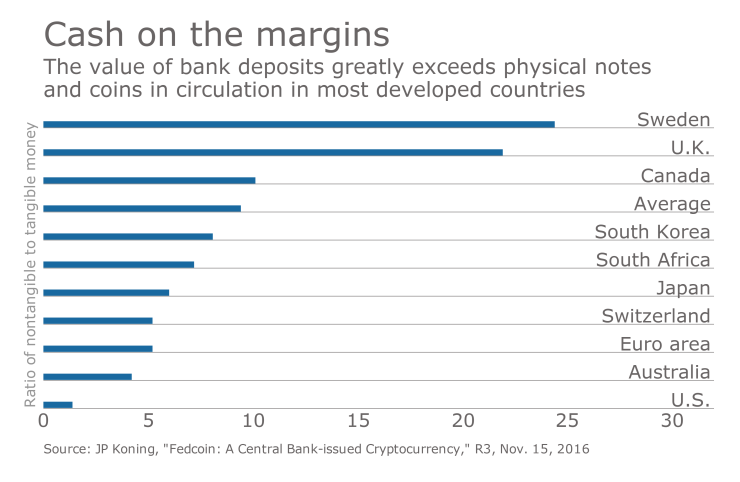

While no society has eliminated notes and coins, there are signs that developed nations may be

"Technology is obviating whatever need there may ever have been for high-denomination notes in legal commerce," he wrote.

Soon after, the European Central Bank announced that it planned to stop producing new 500-euro notes in 2018. The abolition of cash, some experts say, would make it much harder for criminal organizations and tax evaders to stay in the shadows.

Another reason to go cashless, from a central banker's perspective, is that it would allow them to set interest rates below 0% — breaking through what central bankers refer to as the "zero lower bound." This is the theoretical floor on interest rates, since commercial banks being penalized on their deposits at the central bank will have a strong incentive to liquidate them, and average people will empty their bank accounts to hold cash. Cash provides no interest, but its 0% yield is better than a negative rate.

In recent years the European Central Bank and the central banks of Japan and several other countries have shocked the world by setting interest rates below zero. By the middle of 2016, half a billion people were living with "

"When the next financial crisis comes, these central banks will want to set deeply negative interest rates," Koning said. Cash remains an impediment.

The mass adoption of Fedcoin would eliminate the safe haven of cash, giving the central bank more leeway to respond to a recession in an era of already low interest rates. Just as the Fed could offer interest on Fedcoin balances when the economy is strong, so it could penalize them when times are tough.

Not all economists agree that negative interest rate policy is sound. And, at least for now, the Fed has not lost faith in the value of physical cash as a safe store of value and a tool of financial privacy.

The appetite for U.S. banknotes remains healthy both at home and abroad, Powell said during a keynote speech at a blockchain event at Yale Law School this month. Indeed, there is about $1.5 trillion of Federal Reserve notes in circulation, much of it outside the United States.

"My kids live in New York, and they don't know what cash is anymore," Powell said. "But we're not there as a country yet."

A tale of two blockchains

If a central bank were to begin offering digital cash to consumers, what sort of system would it use to issue the new currency? There are two basic options: a permissioned or a permissionless blockchain.

Permissionless blockchains, like bitcoin's, allows anyone to participate and tend not to require participants to link their real identities to their transactions. They do the best job of replicating the anonymity (or near-anonymity) and

Permissioned blockchains are best thought of as proprietary solutions, closed networks with a limited number of known, authorized participants, such as a private company might build for itself. They are designed with regulatory compliance and speed in mind. The limited number of users and the fact that they can be trusted means that transactions clear much more quickly and the network can handle a greater volume of payments — important features for Fedcoin.

Financial institutions and large tech firms have been putting the lion's share of their resources devoted to blockchain research into studying and developing the permissioned kind. Indeed, since 2015, such companies have sought to separate blockchain technology from digital currency, seizing on the former as a superior form of recordkeeping that could cut back-office costs. But there is only so much you can do with a ledger alone.

The fundamental reason why a central bank-issued digital currency is so important, said Rod Garratt, who serves as senior economic adviser to R3, "has to do with the distinction between clearing and settlement. Digital ledgers are great for keeping track of stuff — who owns what — but to fully utilize the benefits of distributed ledger technology we need a settlement instrument."

That's where Fedcoin comes in.

The fate of private banks

In his original 2014

"As the public shifted out of private bank deposits and into Fedcoin, banks would have to sell off their loan portfolios, the entire banking industry shrinking into irrelevance," Koning said.

His concerns are shared by some economists, as well as by Victoria Cleland, the cashier of the Bank of England. A central bank-issued digital currency, she said in September, could "fundamentally change the structure of the financial system." If it competed for users — customers — with commercial banks, it could cause "a reduction in deposit funding available to commercial banks, undermining their ability to provide credit to consumers."

After studying the issue in greater depth, however, Koning takes a more measured view in the R3 report. He has dug up historical examples in which commercial banks were able to hold off a direct challenge from central banks or government-issued money.

One example is postal banking. From 1911 to 1966, the U.S. Postal Service provided savings accounts to consumers in competition with financial institutions. And, in those years following the Panic of 1907, in which a number of banks had collapsed, it didn't shy away from laying on noble rhetoric about being above the profit motive — having, indeed, a motive "infinitely higher and more important . . . to encourage thrift and economy among all classes of citizens." Yet private banks hung on, surely in part because they were willing to offer 3.5% interest on customer deposits while Postal Service accounts offered only 2%.

Another example is the Bank of England, which offered deposit accounts to retail customers until well into the 20th century. In 1855, Queen Victoria's own household left its private bank to do business with the Bank of England's Western branch.

But not everyone made the switch. While private banks paid interest on accounts, the Bank of England paid none. It even charged customers whose accounts were unprofitable. Private banks were therefore able to survive the threat of government-issued, nontangible money by offering customers more favorable terms.

In banknotes, too, the private sector has at times held its own. For decades in Canada, until the nation's central bank was created in 1935, government-issued Dominion notes shared wallet space with paper monies issued by the Royal Bank of Canada, the Bank of Montreal and other institutions. These privately issued currencies disappeared only after being regulated — not competed — out of existence.

So maybe the fears that Fedcoin could cause a meltdown in the banking system are overblown. Private banks would need to "step up their game" in response to Fedcoin, Koning said, "but it's not a bank killer."

Struggling to find the sweet spot

Banks can rest easy — for now. Despite distributed-ledger proofs of concept built by the Bank of England and other central banks, any Fedcoin-style proposal appears to be years away from implementation. In a speech last September, Cleland said the U.K.'s central bank has embarked on a multiyear program to study "the potential economic impact of extending access to central bank money."

A number of technical challenges remain. Powell expressed doubts about the Fed's ability to keep a generally circulating digital currency safe and secure from cyberattacks, theft and even counterfeiting. While advanced cryptography could minimize cyberattacks, he said, it could also make it easier to hide money from the authorities. Improvements in computer technology could make the currency more secure but could also increase the severity of cyberattacks.

After consulting with fintech startups and building its own proof of concept, the Bank of England concluded that distributed ledger technology in its current form is not yet ready to meet its standards for performance, said Andrew Hauser, the bank's executive director of banking, payments and financial resilience. The main challenge, he said, was finding the sweet spot between the competing demands of speed, scale, resilience and trust.

At the Yale event, Hauser described his team's excitement after the bank's initial research suggested that issuing a digital currency could yield significant economic gains — raising the U.K.'s GDP by several percentage points. But as the technical and policy challenges became clearer — including the risk to the private banking sector — it "threw cold water" on their initial enthusiasm, he said.

In the U.S., the Fed confronts many of the same obstacles. Among them is the question of whether the central bank would have to keep extensive records of Fedcoin users' transactions, as commercial banks do today with records of their customers' debits and credits. Such information in the hands of the Fed would raise significant privacy concerns, Powell said.

When asked at Yale who would be allowed to open a Fedcoin wallet and spend digital currency issued by the nation's central bank, Powell was emphatic about where his institution stands.

"The Fed is not considering issuing a digital currency," he said. "It's not something we're looking at doing. We're not at a place where I think that's going to happen."

Another way: CADCoin

A central bank-issued digital currency doesn't have to take the form of digital cash. Rather than a full-fledged Fedcoin it could be merely a more efficient, decentralized version of Fedwire, the central bank's large-value transaction system. Instead of being available to the public, it would serve only the needs of member banks.

"All countries have large-value payment systems," Garratt said. "It doesn't really matter to the consumer what that payment system looks like as long as it functions well."

One prototype for such a next-generation payment system, from the Bank of Canada, goes by the name of CADCoin. In a joint experiment with R3 and the five largest Canadian banks, the central bank set up an asset registry in which participating financial institutions exchanged cash collateral for digital currency generated by the central bank, which could then be used amongst themselves to settle transactions. In the end, the CADCoin could be redeemed for cash.

Only briefly mentioned in the R3 report, CADCoin represents a closed system, a permissioned blockchain with known and trusted participants — making it "a different animal altogether" from a digital fiat currency, said Carolyn Wilkins, the senior deputy governor for the Bank of Canada. After a presentation slide describing CADCoin leaked last year from a Canadian payments conference session to which press weren't invited, Wilkins

For now, at least, the Bank of England also appears to have backed away from Fedcoin. Hauser said that his institution is focused on rebuilding Real Time Gross Settlement, the system it uses for real-time electronic payments, to allow for a "wide range" of private-sector distributed ledger offerings to be built on top of it.

The fate of bitcoin

Far off as the prospect may still be, what would happen to bitcoin and other privately issued cryptocurrencies if a stable, interest-bearing, central bank-backed digital money arrived on the scene?

At the very least, Koning said, it would give them a run for their money. But alternative cryptocoins may not die out completely — at least not as speculative commodities. Some bitcoin users are attracted by its wild price swings, just as there are people who speculate in penny stocks. Since the price of Fedcoin, unlike bitcoin's, would not be volatile, "pretty much anyone who wants to speculate in cryptocoins would still use bitcoin," Koning said.

But for everyday transactions, Fedcoin looks like the clear winner.

"Anyone who just wants to use cryptocoins as a medium of exchange for buying jeans, or groceries, or whatever, those people are going to be attracted to something like Fedcoin," Koning said. "And those people won't be using bitcoin, because it's too volatile."

Ironically, the competitive edge that Fedcoin would likely have over bitcoin and other alternatives is one of the things that makes the Fed hesitant to mint it in the first place.

Powell said he expects private-sector distributed ledger systems to be more innovative and in some ways superior to whatever might come out of a central bank. By competing with these systems, a system run by the Fed — including a digital currency — would "run the risk of stifling innovation."

But it would hardly be the first time the federal government decided to take matters into its own hands rather than letting a thousand flowers bloom in the private sector. If the central bank of a major country does create its own cashlike digital currency in the years to come, says Koning, the people who are holding bitcoin in the belief that it is the universal money of the future might decide they are wrong after all.