WASHINGTON — The largest banks operating in the U.S. all passed the Federal Reserve’s annual stress test for the first time on Wednesday, providing ammunition for those in the industry seeking to dial back their intensity.

But even if those efforts are successful, much of the stress testing processes have already been internalized by banks and the Fed's supervisory grip is unlikely to loosen much.

“Let’s not go too far in declaring victory," said David Wright, a former Federal Reserve Board official and now managing director of banking and securities at Deloitte. "The next shift will be to operationalize this, streamline this further to make this more ingrained in everyday decisions.”

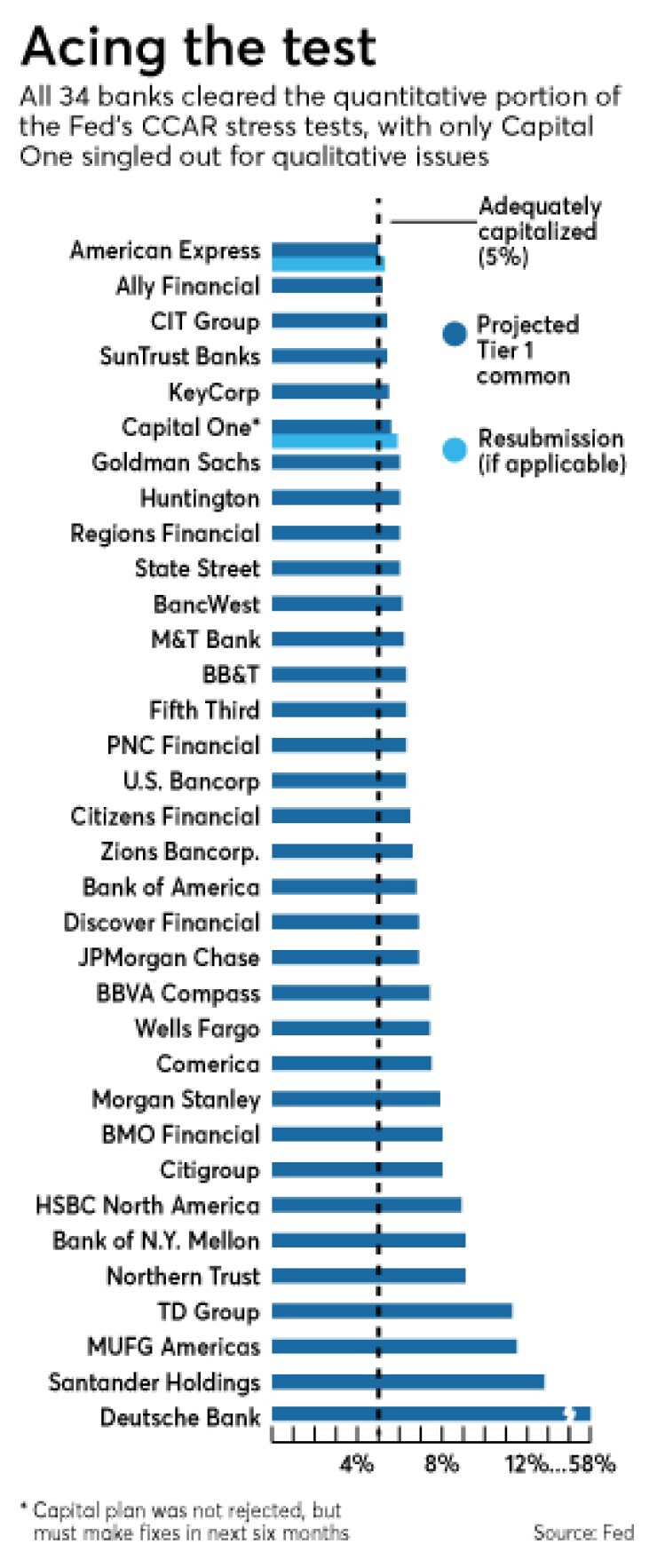

There was little doubt that the news was mostly good for big banks. The results of the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review stress test found that all 34 banks examined met the minimum capital requirements under severely adverse economic conditions. For the first time since the test started, none of the banks had their capital plans rejected for either qualitative or quantitative reasons. Only Capital One received a conditional nonobjection, allowing it to enact its capital plan but requiring it to submit changes by yearend.

Fed Gov. Jerome Powell, who chairs the Fed board’s supervisory committee, said the test’s results demonstrate that the U.S. banking system is safe and secure.

“I’m pleased that the CCAR process has motivated all of the largest banks to achieve healthy capital levels and most to substantially improve their capital planning processes,” Powell said.

Industry advocates immediately seized on the results, arguing that the exercise is unnecessarily burdensome and costly.

“Today’s CCAR results show America’s banks are strong, safe, and ready to boost economic growth by deploying sidelined capital back into our communities,” said Richard Foster, senior vice president and senior counsel for regulatory and legal affairs at the Financial Services Roundtable. “Moving forward, the Federal Reserve Board should implement the Treasury Department’s recent recommendations to modernize the capital planning review process and add needed transparency and accountability measures.”

Oliver Ireland, a former Fed official and partner at Morrison Foerster, echoed that sentiment, questioning whether the Fed can achieve the same level of safety in a less intrusive way.

“Now that we have demonstrated that that banks can not only raise capital but also tailor their risks to the capital raised, it's time to ask whether we have the number right and whether there are less costly ways to achieve the same goals,” Ireland said.

But Bill Lang, a former Philadelphia Fed official and managing director at Promontory, said the Fed has broad supervisory authority over firms – power upon which the CCAR process is based – and so even if the central bank were to make stress testing part of routine supervision, the Fed still can affect banks' ability to pay dividends and make other capital allocations.

“That’s the question that the Fed and other regulators need to wrestle with,” Lang said. “If they need to keep companies on their toes, they have other means that might be just as effective.”

Wright said shifting the qualitative stress testing examination to a more routine exercise – as the Treasury report has suggested– comes with some risk of market complacency. But the banks have also built up the capability to make those examinations more routine, largely at the Fed’s direction.

“There is a possibility of some complacency, but here’s the good news: everyone invested the time and money to get this to a place where it can be done through business-as-usual,” Wright said.

Lang added that there are several areas that the banks still need to improve, even if those concerns don’t rise to the level of a qualitative objection. Those areas include data governance, model risk management and data quality.

Wright agreed, saying the banks may have improved, but Wednesday’s results show they still have a way to go.

“Data quality is a really challenging area, and one that many firms still struggle with and are trying to get right,” Wright said.

That was particularly true for Capital One Financial Corp., which received a conditional nonobjection from the Fed based on weaknesses in the firm’s “oversight and execution of the firm’s capital planning practices, which undermined the reliability of the firm’s forward-looking assessment of its capital adequacy under stress.

“Specifically, the firm’s capital plan did not appropriately take into account the potential impact of the risks in one of its most material businesses,” the Fed report said. “Further, the firm’s internal controls functions, including independent risk management, did not identify these material weaknesses in the firm’s capital planning practices.”

Capital One has until Dec. 28 to resubmit a revised capital plan.

Richard Fairbank, the chairman and CEO of Capital One, said the firm will resubmit its capital plan and expects to have an update on its capital distributions related to those adjustments by the time of its second quarter earnings call.

"We will resubmit our capital plan and are fully committed to addressing the Federal Reserve's concerns with our capital planning process in a timely manner," he said in a press release. "Consistent with our normal quarter-end processes, we expect to affirm or update our guidance on our second quarter earnings call scheduled for July 20, 2017."

Each of the banks subject to CCAR received their initial results ahead of publication and may submit adjusted plans if any of their post-stress minimums fall below the regulatory requirements. American Express Company did precisely that after its initial total capital level fell to 7.8% in the severely adverse scenario — just shy of the 8% minimum required. The firm’s resubmitted plan showed a 8.1% post-stress minimum total capital ratio.

Capital One also resubmitted its plan even though none of its initial quantitative levels fell below the required minimum.

Two banks that notably were not singled out in the 2017 stress tests were Deutsche Bank Trust Corp. and Santander Holdings USA, both of which had faced qualitative

Specifically, the Fed said some firms have not yet been able to identify risks associated with new products and services, may be an overly optimistic loss estimation and need to improve controls for data accuracy and model risk.

Wednesday’s CCAR results complete the 2017 round of the Fed’s stress tests, which has

The tests are similar in many ways. Both take a bank’s balance sheet and run it through nine future quarters of hypothetical economic conditions developed by the Fed to approximate stress conditions of varying intensity. The severely adverse scenario is generally calibrated to be at least as adverse as the 2008 financial crisis. Banks are examined using both Fed models and internal bank models to see whether the firms’ balance sheets remain above minimum capital levels.

One important difference between DFAST and CCAR is that CCAR takes into account banks’ actual capital plans, whereas DFAST uses standardized assumptions. A more important difference is that there is no penalty for banks failing to meet the minimum capital requirements in DFAST, whereas banks can have their dividend payments reduced or eliminated for failure to meet the capital requirements. CCAR also includes not only quantitative but qualitative examinations, requiring the banks’ models to meet certain specifications.

In the

The 2017 CCAR results included for the first time a detailed discussion of the central bank’s qualitative examination process, an effort that a senior Fed official was intended to give the public further insight into how that test is performed. The Fed said it uses six criteria: governance, risk management, internal controls, capital policy, scenario design and projection methodologies. The Fed included real, albeit sanitized, situations where banks received objections based on each of those criteria.

Wednesday’s results come as the Fed’s stress testing regime – particularly the CCAR program – is coming under heightened scrutiny from lawmakers and the Trump administration. Banks and other industry groups have said the program has outlived its usefulness now that the banking sector is better capitalized and more aware of its own business dealings than it was before the crisis.