As reports have rolled in that Wells Fargo employees opened more than 2 million fake accounts to meet sales goals or secure bonuses, and that 5,300 workers were fired, personal failings and human judgment have been at the heart of the debate.

Regardless of where the fault lies — with branch employees or upper management — the failure of humans to act with honesty and integrity raises an oft-repeated question these days: Could technology have prevented the problem?

It certainly could have helped Wells put checks in place that would have ensured employees could not set up bogus accounts — and could help other banks from following in its footsteps, tech experts say.

"Systems that are used to detect fraudulent account openings and transactions can be adapted to detect internal shenanigans as well," said David Mooney, president and chief executive of Alliant Credit Union, which is headquartered in Chicago with members nationwide. "This is a particularly good application for artificial intelligence and intelligent machines, which can scan large amounts of public and internal data and identify patterns."

Mooney serves on the advisory board of a company called Datanomers that does this for telecom companies. More on that later.

"Whenever incentives-based selling is in place with front-line employees, there should be a series of risk management checks in place, and regular and visible audits to detect abuse," said Al Pascual, head of fraud and security at Javelin Strategy & Research.

The accusations against Wells employees included setting up accounts customers did not request, funding those accounts by transferring funds from other accounts without telling customers, creating phony email addresses and setting PIN numbers for unknown and unwanted debit cards.

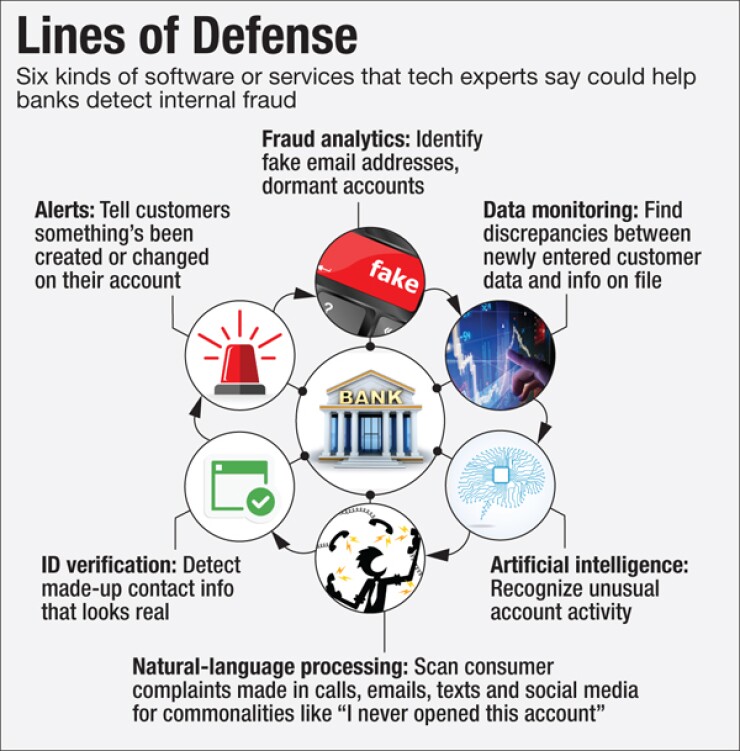

What type of technology would be most effective? There are several options.

Analytics and AI

Fraud analytics software could be adapted to look for signs of doctored contact information such as fake email addresses like

Pascual, however, does not see traditional fraud analytic tools as an effective deterrent to employee fraud. "They're not necessarily designed to mitigate that kind of risk," he warned. "They're looking for indications that an external bad actor is attempting to act in place of a legitimate customer. How are they supposed to know when it's an employee?"

Indeed, FICO confirmed that its popular Falcon fraud-analytics software, used by more than 90% of banks, is typically used to monitor for third-party fraud on existing active accounts, not in-house fraud on dormant accounts.

Data monitoring, a related technology sometimes used to protect the improper viewing of sensitive information, could also be applied here.

The fintech startup BigID monitors customer data and compares newly entered data against data in archives and applications to find anomalies.

A mortgage application might have one set of information about a customer while a credit card application has very different data, for instance, including a different email address. Of course, this is not a sure sign of fraud because many people maintain multiple email accounts.

"Email alone is rarely enough to indict anybody, but it may be enough to raise alerts," CEO Dimitri Sirota said. A bank might set an alert that is triggered any time there are three or more data disparities. Such software might also look for a pattern of an email address changing right before a new account is created.

"People do this for security today" to detect the work of hackers, Sirota noted. "But now people are thinking about it in terms of personal data privacy and protection."

Artificial intelligence is another possible answer.

"The fiasco at Wells Fargo is the typical outcome of where you don't know what your baseline, your norm looks like," said Deepak Dube, founder and CEO of Datanomers, an AI spinoff from IPsoft whose technology is used to detect fraud in telcos. "This is prevalent in banks, whether it's the London Whale fraud in London for JPMorgan Chase or fake accounts at Wells Fargo. If you can build for an organization as large as Wells Fargo what your statistical norm looks like, then you can study deviant behavior."

An artificial intelligence machine could learn to understand what is normal for accountholder characteristics, including diversity of email addresses, distribution of active versus inactive accounts, and where accounts are typically opened and in what numbers, for instance. Then when patterns of deviation appear, executive management can be alerted there was something funny going on," Dube said.

Datanomers also uses a natural-language-processing technology from IPsoft called Amelia that performs semantic analysis on calls, emails and other customer-care interactions to spot themes in complaints. If lots of customers say they are being charged for an account they never wanted, that suggests a pervasive problem.

Obtaining Digital Consent

Being able to prove customers agreed to a new account or product may become critical in the wake of the scandal.

"If I'm the head of retail or the CEO at any bank, I'm looking at what happened to Wells Fargo and thinking, why wouldn't the [Consumer Financial Protection Bureau] come after me and say hey, you say you have operational controls, show me proof that customers were involved in these transactions?" said David Eads, CEO of Gro Solutions, a provider of account-opening software. "In my experience, about 80% of the products at a bank are sold in the branch, and you have the fox in the henhouse."

In Eads' view, the continued use of paper forms and antiquated branch systems provides an opening for fraud.

"There's nothing in there that proves the customer authorized the opening of that account," Eads said. "We're taking the employee's word for it, and the employee all the way up to the CEO is incented on the number of accounts and relationships."

Electronic signature software could capture the customer's assent to purchase a product. It could be augmented with biometrics such as fingerprint or iris scans to ensure the validity of the customer input.

BigID has developed technology that tracks consent agreements.

So if a customer looks at a product offer in a web app and clicks "I Agree," the bank will get a record of when and where that consent took place. To prevent an employee from providing the consent, the bank could build in a requirement that it has to come from the customer's desktop or mobile device.

The company has reached out to Wells Fargo to offer this software but hadn't gotten a call back yet, its CEO Sirota said.

"The issue with electronic signatures is that they still must be authenticated," Mooney pointed out. "One would need to make sure that an employee could not somehow set themselves up as an electronic signatory on the account. It might be a future application for blockchain."

Verification and Notifications

Identity verification tools could be used to detect the use of made-up contact information that looks real. Emailage, for instance, verifies email addresses. "Even at the most basic level you can look for illegitimate email addresses that don't fit the typical format," Pascual said. Informatica and LexisNexis are among the other providers of services that verify contact information.

With the contact information vetted, technology that automatically notifies the customer of account or product changes would also be useful. "You definitely want to have notifications in place," Pascual said. "In a bank that relies heavily on cross-sales, you probably have established relationships where contact information has been on file for a while, so notifying customers whenever a new account of any kind is opened is easy to do. It's also good customer service."

The notification should obviously take place in a different channel than the account opening itself. If a new credit card is opened in a branch, the customer could be notified by paper mail, text or email.

Wells Fargo CEO John Stumpf testified before Congress on Tuesday that in the future, the bank will send confirmation emails to customers within one hour of the opening of a new deposit account.

Big Brother Is Watching

As these technologies are implemented, Pascual recommends telling employees about them, so they know they could get caught. He also stresses the need for clearly defined, communicated and enforced consequences for violations to deter this type of behavior.

"If that's not happening, people will run amok," Pascual said.

He's loath to blame aggressive sales goals for the problems at Wells Fargo. "It's easy to make that the driving reason, but people could be pressured just by thinking they need money — they have bills to pay, they have a sick family member," he said.

"The fact is, if people feel like no one's watching, they will try to get away with things," Pascual said.

Editor at Large Penny Crosman welcomes feedback at