-

The pairing of Rockville Financial in Connecticut and United Financial in Massachusetts would create a $5 billion-asset bank that can get more efficient yet invest in growth. More deals like it have been happening around the country this year.

November 15 -

To prove the value of the merger of Provident New York Bancorp and Sterling Bancorp, executives have to increase revenues at a much faster pace than expenses over the long haul, CEO Jack Kopnisky says.

November 5 -

Provident New York says the addition of Sterling Bancorp will super-size returns. Analysts are sold on the combo but question whether the profitability projections for it are realistic.

April 5 -

ViewPoint Financial Group is acquiring LegacyTexas in hopes of creating a large community bank solely focused on the greater Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area, bucking a 2013 trend in Texas and across the country of using M&A to enter complementary markets.

December 3

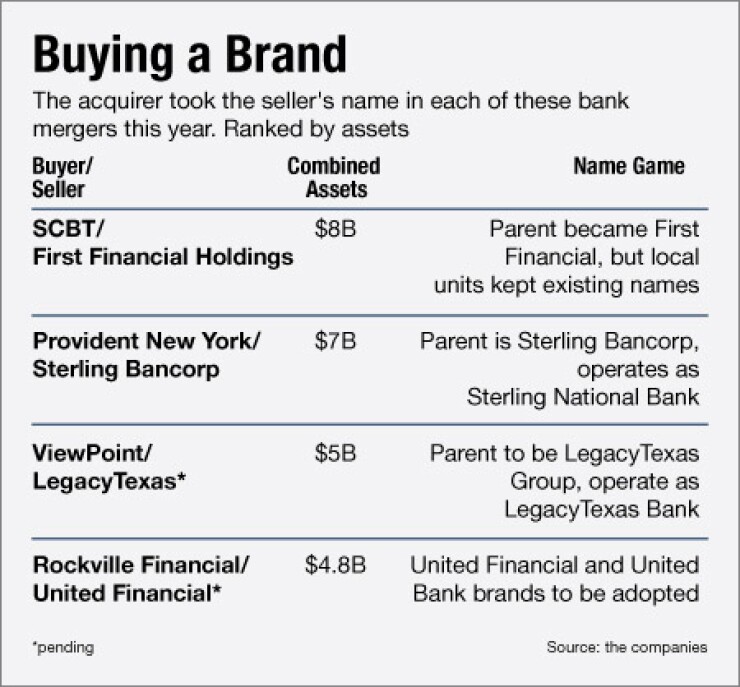

Bank buyers these days really want their deals to be viewed as partnerships, which require give-and-take.

They are giving stock to the sellers and making important concessions, even regarding what to name the new bank. In a handful of the largest deals this year, the seller's brand is the one that survived. All of those deals were sold to investors as an alliance and sometimes described as a merger of equals.

Such deals make so much sense in the current environment: two banks in the same or complementary markets think they can weather the current economic and regulatory environment better and provide stronger returns for their shareholders by joining forces and eliminating redundant costs. Investors have embraced the concept, as stock increases at the buyers have shown.

However, negotiations entail a complex dance of legacies, pride, board compositions and other social issues, before even arriving at a price. Such deals promise financial and strategic benefits, but they are the hardest to pull off, M&A advisors say.

It comes down to cooperation, says William H. W. Crawford 4th, chief executive of Rockville Financial (RCKB) in Connecticut. Last month,

"We really like the Rockville name, it has meant a lot to our community, but at the end of the day the right thing to do was to get this deal done," Crawford says. "Both sides had to give up a lot of different things and name was one of the things we had to give up."

In the same interview, Richard Collins, the chairman and CEO of United who will retire when the deal is completed, points out that the name United is not restricted to a single geography like Rockville is. Crawford agrees.

"'United' is a name that travels well," Collins says. "Maybe that's why there are so many 'Uniteds' around."

With an ownership split of 49% Rockville/51% United and a 20-person board with equal representation from both companies, analysts like Mark Fitzgibbon of Sandler O'Neill have described it as the "most equal of the MOEs we've seen this year."

The name-related compromise makes sense, advisors say. Go with the best one is their advice.

"In most cases what you are seeing are the companies going with what they view as the better name, [the one that] is going to give them a broader application in the market," says Brian Sterling, principal and co-head of investment banking at Sandler O'Neill, which wrote a fairness opinion on the Rockville-United deal.

In some cases, there is a marriage of practical reasons and pride.

"It was definitely important to Lou and the board for 'Sterling' to remain in existence, even if it wasn't the legal surviving entity" Fitzgibbon says.

Damon Delmonte, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, says the naming compromise is a good signal that bankers are seeing the bigger point in negotiating: the companies are better off together and that they should do what they can to make it happen.

"It is sign that they are truly trying to create as friendly a deal as possible," Delmonte says.

It is not all singing Kumbaya, though. There is a competitive advantage to agreeing to take on the seller's name, says Kevin Hanigan, chief executive of ViewPoint Financial in Plano, Texas, which

"In deals, we all have concerns about what if someone shows up and tops your bid," Hanigan says. A larger buyer wouldn't be willing to change its name. "It makes it more difficult."

Still, the most important reason for the switch is that LegacyTexas is a better name, Hanigan says. He knew that from a marketing study even before approaching LegacyTexas.

Hanigan was the one who suggested the name change, and it is a good thing he did.

"Kevin and his team are really appealing, but ViewPoint as a brand wasn't as favorable to us," says Aaron Shelby, an executive vice president of LegacyTexas. The Shelby family owns a 75% stake in LegacyTexas. "I don't know that it would have killed the deal, but it was a factor to us. I don't think we would have been quite as excited without it."