-

Persistent challenges such as margin compression and rising expenses will eventually force more banks to sell.

January 28 -

Executives at FirstMerit, PNC and KeyCorp — which have acquired branches in deals in recent years — are seeking to wring substantial cost savings from their brick-and-mortar networks and rely more on high-tech services.

September 10

Community banks can no longer settle for good branch locations — they need great ones.

Banks are closing branches at a rapid pace in an effort to pad bottom lines and react to declining foot traffic. So small banks must rely more on data and an understanding of local markets for branching decisions, industry observers say.

Smarter decisions on branching could be what helps community banks survive, says Robert Kafafian, president and CEO of Kafafian Group. "Competition isn't getting easier and regulation is a burden," he says. Banks "need to keep their current customers. They have to tap into all … available resources to help themselves."

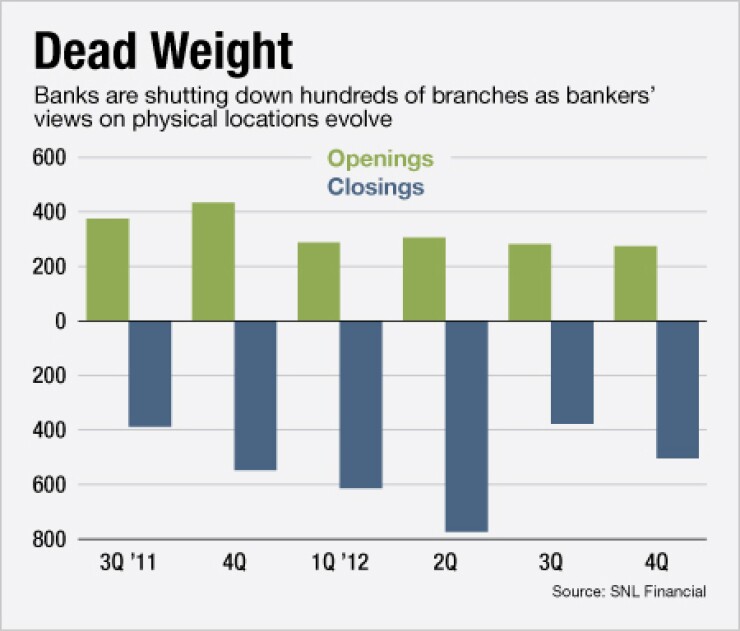

Branch traffic is off 40% from five years earlier, says Lynn David, chief executive of Community Bank Consulting Services. In the fourth quarter, banks closed 503 branches and opened 274, according to SNL Financial. The net decline more than doubled that of a quarter earlier.

Banks once obsessed about density. Now they're emphasizing visibility, says Kevin Travis, a partner at Novantas. Branches and signage should serve as marketing for a bank, he says: "If the branch is the bank, then I need to see it to know it's there."

As a result, branches with less visibility have less value and it no longer makes sense to pay the overhead to run them. Banks also need to determine if a branch will add "to the broader network and help the rest of the branches become more profitable," Travis says.

Every branch "is pretty expensive," Travis says. "I want to get the most usage I can … so I need to put it in the highest-visibility location that I can. People need to know that the branch is around. An invisible branch is expensive and doesn't help the company."

Visibility is important for marketing Opus Bank, says Stephen Gordon, the $2.7 billion-asset company's chairman and CEO. The Irvine, Calif., company opened 16 branches in the last 18 months. It plans to

Opus targets densely populated areas to gain access to a "deep presence of deposits" and a concentration of businesses and real estate opportunities, Gordon says. Opus looks for high traffic areas like upscale retail centers with businesses such as Whole Foods and Starbucks. These are "destinations for customers where there are reasons for people to go there," he says.

Small banks must change how they think about markets, industry experts say. Banks need to consider where customers live and work and the establishments that they frequently visit.

Banks often misunderstand "where their customers are coming from and why," Kafafian says. "You are maybe offering the wrong products or setting up in the wrong locations. A lot of banks don't have the wherewithal to get that kind of data."

Kafafian recalls working with a New Jersey bank that assumed most of its customers lived along the Jersey shore.

After completing research, the bank found that half of its clients were in the northern part of the state; their summer homes were near the shore. That information helped the bank make better decisions about its branches, Kafafian says.

Banks need to track data, such as customers' home and work addresses, ATM patterns, and the types of transactions completed at a branch, Travis says. Banks also need to figure out how many customers only bank online.

Banks must make sure that their branches are convenient for the types of customers they want to attract, says Mary Beth Sullivan, a managing partner at Capital Performance Group. Understanding traffic patterns and customer movement is essential. If a bank has mass-market appeal, then it makes sense to have branches in shopping centers where middle-income customers are apt to go, she says.

"All banks, including community banks, need to be more sophisticated in how they allocate their resources," Sullivan says. "Resources are scarce today and they will only get scarcer."

Two River Community Bank in Middletown, N.J., focuses on small businesses and commercial loans, including to the medical sector, says Rob Werner, the bank's chief operating officer. When adding branches, proximity to those customers is a factor, he says.

The $705 million-asset bank, a unit of Community Partners Bancorp, also examines daytime and nighttime populations and traffic patterns of areas. Signage rules also vary by town, which could influence decisions, Werner says. The bank, which opened a loan production office and a branch last year, is looking to expand in Middlesex County in its home state.

"We look at our own customers and where they live," Werner says. "If we start to see a lot of customers living in a particular community and using another branch, that's a factor."

Data can also help bank determine whether to cut hours and close branches. Banks must consider what a closing could do to its broader business, including short-term costs such as buying out a lease, Sullivan says.

Small banks should track the types of transactions tellers handle because it could help determine how many tellers are needed at any given time, David says. He also uses a process that helps banks track the activities of new accounts personnel by breaking days down by increments as small as two minutes.

This analysis helped an Iowa bank shut three branches and reduce hours at half of its remaining branches. "An awful lot of banks don't look at any data, but you have to do the homework," David says.